Chapter 16

H

e flits the brush through the paint. Bernie likes green? Too bad he’ll never see this. It’s a green the likes of which Giles never dreamed possible. How did he mix it? He recalls a base of Caribbean blue, a touch of grape, dapples of harvest orange, streaks of straw yellow, daubs of gloaming indigo, his signature cotton-clay red—what else? He doesn’t know and doesn’t care. He’s coasting on impulse here. It’s rousing, and yet there’s a peace to it as well. His brain doesn’t smart from focus; it rambles and stretches, tying disparate threads together in shiny, department-store bows.Bernie. Good old Bernie Clay. Giles thinks of the last time he saw him. In hindsight, he can see signs of stress all over the guy. The yellowed collar no volume of bleach can scrub, the gut bulging the shirt—Bernie had always been an anxious eater. Giles forgives him. He’s never felt more forgiving. For too long, ill will has clogged his arteries like cholesterol, an ominous substance he just read about in the news. Today, the cholesterol is flushed and only love remains. It flows into his every long-dug trench. The cops who arrested him at the bar in Mount Vernon. The executive cabal that got him fired. Brad—or John—of Dixie Doug’s. Everyone struggles against the qualms and uncertainties that life twines about them.

How had it taken him sixty-three years to recognize the futility of anger? When Mrs. Elaine Strickland, a woman half his age, knew it on instinct? Giles doesn’t believe a dawn will rise that he won’t privately thank her. Just this morning he’d tried calling her at Klein & Saunders to express what her candor had meant to him, how it’d forced open storehouses of courage he’d never suspected he had, but the voice that answered didn’t belong to Elaine, and couldn’t say why Elaine hadn’t shown up to work.

Quite all right with Giles: He has a lifetime’s backlog of patience upon which to draw. Mrs. Strickland is, after all, one of two beings to whom he credits his renaissance. The other is the creature. Giles chuckles in wonder. Elisa’s bathtub has become a portal into the impossible. The work Giles has done alongside it, from atop a toilet seat of all places—he is so thankful to know the sort of divine inspiration typically reserved, he is certain, for only the greatest of masters.

While the creature belongs to no one, no place, and no time, his heart belongs to Elisa, and Giles has left the two of them to share these final hours. Besides, Giles needs to complete his painting. It is, without question, his life’s finest work, and what existential relief there is in knowing you have managed, at last, to live up to your potential. The fulfillment of his hopes is to show the finished piece to the creature before the creature is gone, and that requires working on it day and night.

Working, however, hasn’t been a problem. Twenty hours he’s been at it now and he feels tip-top, as unflagging as a teenager, powered as if by a fabulous drug that has the sole side effect of suffusing him with confidence as powerful as the storm outside. He makes the boldest brushes of color without pause. He paints the finest slivers of detail without arthritic tremor. He hasn’t broken for a bathroom break in half a day, and when was the last time he made it two hours without peeing?

He laughs, and his eye catches a fluttering cloth. It’s the bandage Elisa coiled around his arm. He’s working so briskly that it has come loose. Strange that he hasn’t noticed. More strange, he thinks, is that he hasn’t needed to take aspirin for pain since before bed. Perhaps the cut wasn’t so deep after all. Still, the bandage will trail across wet paint and that won’t do. He sighs, sets down his brush. A quick, fresh dressing—maybe brush his teeth while he’s at it—and then it’s back to the easel! He can hardly wait.

Giles doesn’t realize that he’s whistling a show tune until the jaunty song cuts off. He blames the misperception on his speed: He’s unwrapping the bandage as if reeling in a catfish. He quits unwinding and carefully pushes the rest of the bandage into the sink. There’s no blood. Is he so exhausted that he’s looking at the wrong side of his own arm? He rotates it, finds nothing. Not even a wound, which, last time he checked, was pink and puckered.

He makes a fist, watches the cords of his wrist thicken. The shock of it settles slowly, rescuing him from full impact. The wound isn’t the only thing gone. There used to be liver spots on his arm. There used to be a scar from a youthful collision with a cotton loom. These, too, have been replaced by smooth, perfect skin. Giles checks his other arm. It is as old and wrinkled as ever.

Giles sputters in disbelief. It sounds rather like a laugh. Is that an appropriate reaction to the supernatural? He looks up into the mirror and, sure enough, the deep lines of his face are curved in jubilance. He looks good, he thinks, and notes that he hasn’t held this opinion of himself in more years than he can remember. His eyes flick upward. Ah, there’s the reason. He hadn’t noticed until now.

He has a head full of hair. Giles reaches for it, but slowly, as if it might be scared away. He pats it. It does not scatter like dandelion puffs. It is short and thick, a rich brown with familiar traces of blond and orange. More than that, it’s springy; he’d forgotten the resilience of young hair, how it resists being constrained. He pets it, stunned by the satin texture. It’s erotic. This, he thinks, is why young people are so lustful: Their own bodies are aphrodisiacs. Only after he thinks this does he notice a pressure against the sink. He looks down. His pajama bottoms are tented outward. He has an erection. No, that’s too clinical a word for this adolescent response to the slightest sexual thought. It’s a boner, a hard-on. He can feel youth swell his every molecule with lightness, quickness, pliancy, bravado.

There is a knocking at his door. A pounding, really, a sure sign of emergency next door. Giles knows himself well enough to anticipate a sick, sinking sensation, but whatever has affected his body has also affected his spirit: The alarm he feels is at the end of an upsurge, a tilting toward challenge rather than edging away. He lurches toward the door, mindful enough of the silly pendulum of his erect penis to grab a pillow to hold in front of him. Elisa can’t see him like this! He chuckles, despite everything.

He whips open the door and finds the perspiring, red face of Mr. Arzounian.

“Mr. Gunderson!” he cries.

“Ah, the rent,” Giles sighs. “Tardy, it’s true, but have I ever—”

“It is raining, Mr. Gunderson!”

Giles pauses, allowing the drumroll of rain on the fire escape to interject.

“Well, yes. I can’t argue with you there.”

“No! In my theater! There is rain in my theater!”

“Are you asking me to witness a miracle? Or do you mean a leak?”

“Yes, a leak! From Elisa’s apartment! She leaves the water on! Or else a pipe is broke! She will not answer the door! It comes through the ceiling, right onto paying customers! I will find my keys, Mr. Gunderson, and I will open her door myself if it doesn’t stop! I must go downstairs! Make it stop, Mr. Gunderson, or the both of you will live at the Arcade no more!”

He’s gone then, careening down the stairs. Giles doesn’t need the pillow anymore; he backhands it onto his sofa and jogs, in socked feet, the distance between apartment doors. He swipes the key from its lamp haven, inserts it with a dexterity that delights him, and barges in. He doesn’t know what he expects. More blood? Destruction from some fit of rage? Nothing is amiss until he divines that the floorboards near the bathroom have not been recently mopped. They are, instead, covered in a half-inch of water. He charges, socks soaking as he splashes through the thin pool. This isn’t a situation for knocking; he hurls open the bathroom door.

Water bursts outward, drenching Giles from the knees downward. A day ago, the force of the tide, not to mention the plain shock of it, would have toppled him; today, though, his legs are roots, planted firm even as standing lamps and end tables behind him topple to the floor in the rushing tide and its sloppy cargo of unpotted plants. The edge of a shower curtain, which must have held back the flood, flops like snakeskin onto his socks, revealing Elisa and the creature lying in the center of the floor.

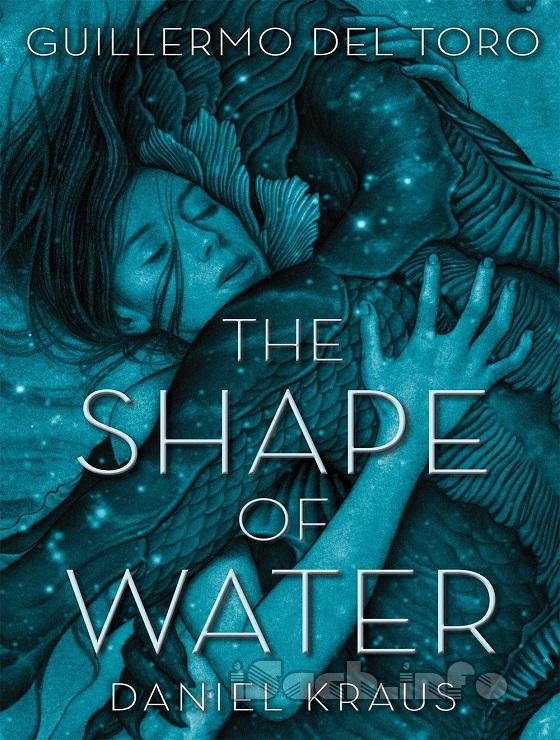

They should be carved in marble in this exact position, Giles thinks, and by someone who knows how—Rodin, Donatello. Elisa is glistening wet, freckled with muddied soil, sparkling with scales, naked. The creature is, too: Though always unclothed, there’s a reckless need to his pose that makes him naked. His arms and legs are interlocked with hers, his face nuzzled into her neck. Her left hand strokes his scalp and cups the back of his head where his ridge of fins begins. He does not look good, and hasn’t in a while; he does, however, look content, as if he has chosen his fate, and does not, even upon pain of death, plan to regret it.

Giles expands his view, and along with it expands the spectacular. The room is a bathroom no more. It has become a jungle. He squints before realizing his vision is perfect, even without glasses. Did their lovemaking, whatever form it took, arouse household mold spores to blossom into rain-forest verdure? No, that’s not it. The plants that withstood the flood are languid, even voluptuous, with moisture, but it’s the hundreds of tree-shaped cardboard air fresheners that have turned the room into an unimaginable wilderness of ravishing color. Shamrock green, lipstick red, sequin gold. Where did Elisa find so many? They are layered over every single inch of wall. Pumpkin orange, coffee brown, butter yellow. The low-budget ingenuity behind the cardboard jungle makes it all the more breathtaking. Amethyst purple, ballet-slipper pink, ocean blue. It is a home not quite Elisa’s and not quite the creature’s; it is one of a kind, a strange heaven built for two.

It takes a while for Elisa to register Giles. Her eyes are half-closed, dreamy. She absently pinches the shower curtain and pulls it over them as she might a bedsheet. Giles’s role, he supposes, is that of the fellow who didn’t knock, and he waits to feel disgusted by the vile, unnatural act he has uncovered. How many times, though, have these same adjectives been applied to people like himself? Today, nothing is wrong; nothing is taboo. Perhaps Mr. Arzounian will kick them out. Giles can’t force himself to care. Just as likely, in this world, Mr. Arzounian doesn’t exist at all.

Giles kneels, tucks the shower curtain around them. New neighbors, he tells himself, happy young lovers who he, newly young himself, will find to be true, long-lasting friends. Elisa blinks up at Giles and extends an arm shimmering with scales. She runs her fingers through his brand-new hair and smiles gently, as if to ask, What did I tell you?

“Can we keep him?” Giles sighs. “Just a little bit longer?”

Elisa laughs, and Giles laughs, too, loudly so that it might echo in the confined chamber and keep the silence of an uncertain future at bay, so that they might go on pretending that this happiness will last forever and that miracles, once found, can be bottled and kept.

ePub

ePub A4

A4