Part III: The Fortune Teller - Monday, May 23 - Chapter 18

W

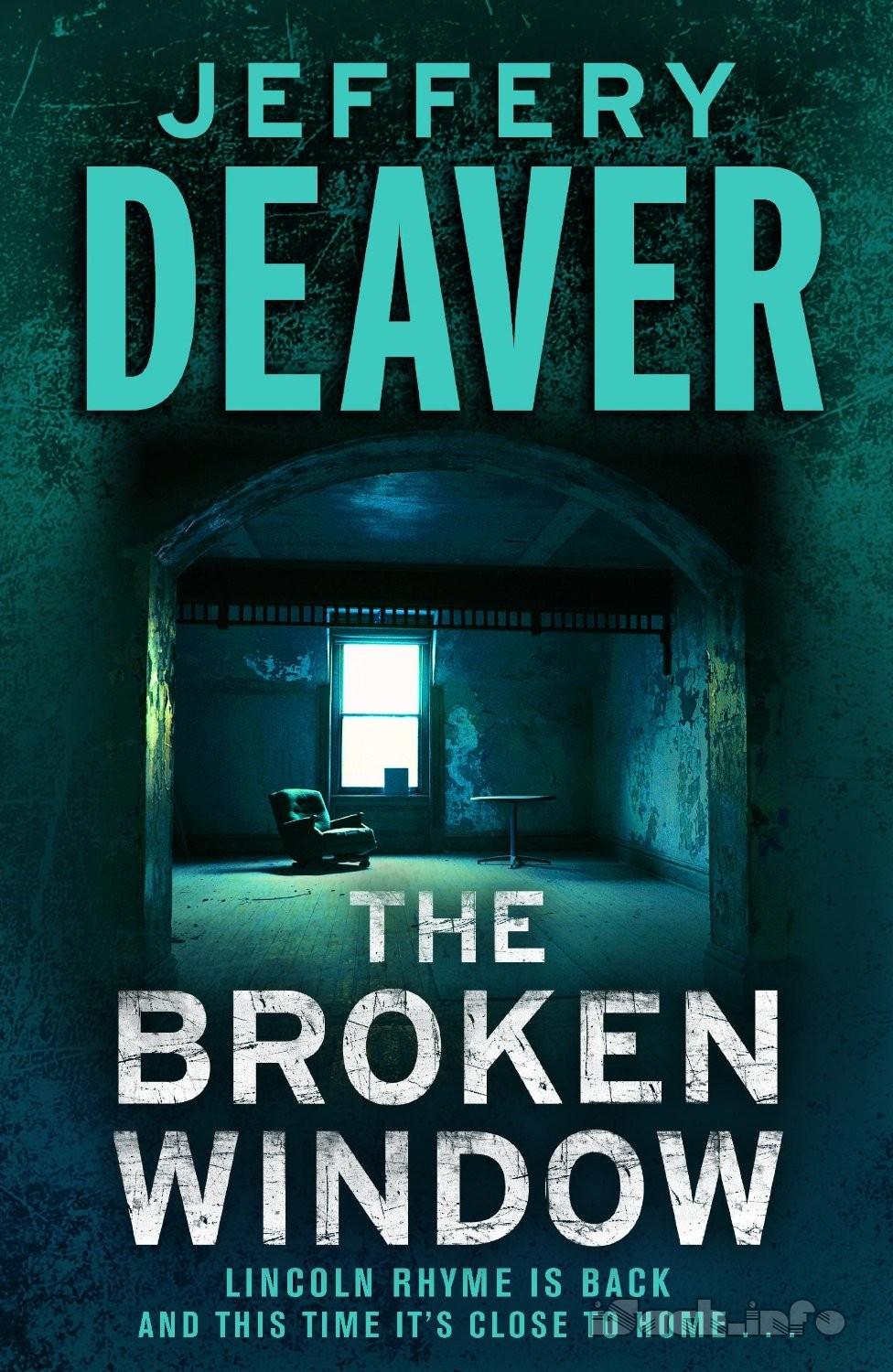

ith uncanny accuracy, computers predict behavior by sifting through mountains of data about customers collected by businesses. Called predictive analytics, this automated crystal ball gazing has become a $2.3 billion industry in the United States and is on track to reach $3 billion by 2008.—CHICAGO TRIBUNE

They’re pretty big…

Amelia Sachs sat in Strategic Systems Datacorp’s sky-high lobby and reflected that the shoe company president’s description of SSD’s data mining operation was, well, pretty understated.

The Midtown building was thirty stories high, a gray spiky monolith, the sides smooth granite flashing with mica. The windows were narrow slits, which was surprising given the stunning views of the city from this location and elevation. She was familiar with the building, dubbed the Gray Rock, but had never known who owned it.

She and Ron Pulaski—no longer in play clothes but wearing a navy suit and navy uniform, respectively—sat facing a massive wall on which were printed the locations of the SSD offices around the world, among them London, Buenos Aires, Mumbai, Singapore, Beijing, Dubai, Sydney and Tokyo.!!!Pretty big…

Above the list of satellite offices was the company logo: the window in the watchtower.

Her gut twisted slightly as she recalled the windows in the abandoned building across the street from Robert Jorgensen’s residence hotel. She recalled Lincoln Rhyme’s words about the incident with the federal agent in Brooklyn.!!!He knew exactly where you were. Which means he was watching. Be careful, Sachs…

Looking around the lobby, she saw a half dozen businesspeople waiting here, many of them uneasy, it seemed, and she recalled the shoe company president and his concern about losing SSD’s services. She then saw, almost en masse, their heads swivel, looking past the receptionist. They were watching a short man, youthful, enter the lobby and walk directly toward Sachs and Pulaski over the black-and-white rugs. His posture was perfect and his stride long. The sandy-haired man nodded and smiled, offering a fast greeting—by name—to nearly everybody here.

A presidential candidate. That was Sachs’s first impression.

But he didn’t stop until he came to the officers. “Good morning. I’m Andrew Sterling.”

“Detective Sachs. This is Officer Pulaski.”

Sterling was shorter than Sachs by several inches but he seemed quite fit and had broad shoulders. His immaculate white shirt featured a starched collar and cuffs. His arms seemed muscular; the jacket was tight-fitting. No jewelry. Crinkles radiated from the corners of his green eyes when that easy smile crossed his face.

“Let’s go to my office.”

The head of such a big company… yet he’d come to them, rather than having an underling escort them to his throne room.

Sterling walked easily down the wide, quiet halls. He greeted every employee, sometimes asking questions about their weekends. They ate up his smiles at reports of an enjoyable weekend and his frowns at word of ill relatives or canceled games. There were dozens of them, and he made a personal comment to each.

“Hello, Tony,” he said to a janitor, who was emptying the contents of shredded documents into a large plastic bag. “Did you see the game?”

“No, Andrew, I missed it. Had too much to do.”

“Maybe we should start three-day weekends,” Sterling joked.

“I’d vote for that, Andrew.”

And they continued down the hall.

Sachs didn’t think she knew as many in the NYPD as Sterling said hello to in their five-minute walk.

The decor of the company was minimal: some small, tasteful photographs and sketches—none in color—overwhelmed by the spotless white walls. The furniture, also black or white, was simple—expensive Ikea. It was a statement of some kind, she guessed, but she found it bleak.

As they walked, she ran through what she’d learned last night, after saying good night to Pam. The man’s bio, patched together from the Web, was sparse. He was an intensely reclusive man—a Howard Hughes, not a Bill Gates. His early life was a mystery. She’d found no references at all to his childhood, or his parents. A few sketchy pieces in the press had put him on the radar at age seventeen, when he’d had his first jobs, mostly in sales, working door-to-door and telemarketing, moving up to bigger, more expensive products. Finally computers. For a kid with “7/8 of a bachelor’s degree from a night school,” Sterling told the press, he found himself a successful salesman. He’d gone back to college, finishing the last one-eighth of the degree and completing a master’s in computer science and engineering in short order. The stories were all very Horatio Alger and included only details that boosted his savvy and status as a businessman.

Then, in his twenties, had come the “great awakening,” he said, sounding like a Chinese communist dictator. Sterling was selling a lot of computers but not enough to satisfy him. Why wasn’t he more successful? He wasn’t lazy. He wasn’t stupid.

Then he realized the problem: He was inefficient.

And so were a lot of other salesmen.

So Sterling learned computer programming and spent weeks of eighteen-hour days, in a dark room, writing software. He hocked everything and started a company, one based on a concept that was either foolish or brilliant: Its most valuable asset wouldn’t be owned by his company but by millions of other people, much of it free for the taking—information about themselves. Sterling began compiling a database that included potential customers in a number of service and manufacturing markets, the demographics of the area in which they were located, their income, marital status, the good or bad news about their financial and legal and tax situations, and as much other information—personal and professional—as he could buy, steal or otherwise find. “If there’s a fact out there, I want it,” he was quoted as saying.

The software he wrote, the early version of the Watchtower database management system, was revolutionary at the time, an exponential leap over the famed SQL—pronounced “sequel,” Sachs had learned—program. In minutes Watchtower would decide which customers would be worthwhile to call on and how to seduce them, and which weren’t worth the effort (but whose names might be sold to other companies for their own pitches).

The company grew like a monster in a science fiction film. Sterling changed the name to SSD, moved it to Manhattan and began to collect smaller companies in the information business to add to his empire. Though unpopular with privacy rights organizations, there’d never been a hint of a scandal at SSD, à la Enron. Employees had to earn their salaries—no one received obscenely high Wall Street bonuses—but if the company profited, so did they. SSD offered tuition and home-purchasing assistance, internships for children, and parents were given a year of maternity or paternity leave. The company was known for the familial way it treated its workers and Sterling encouraged hiring spouses, parents and children. Every month he sponsored motivational and team-building retreats.

The CEO was secretive about his personal life, though Sachs learned that he didn’t smoke or drink and that no one had ever heard him utter an obscenity. He lived modestly, took a surprisingly small salary and kept his wealth in SSD stock. He shunned the New York social scene. No fast cars, no private jets. Despite his respect for the family unit among SSD employees, Sterling was twice divorced and unmarried at the moment. There were conflicting reports about children he’d fathered in his youth. He had several residences but he kept their whereabouts out of the public record. Perhaps because he knew the power of data, Andrew Sterling appreciated its dangers too.

Sterling, Sachs and Pulaski now came to the end of a long corridor and entered an exterior office, where two assistants had their desks, both of which were filled with perfectly ordered stacks of papers, file folders, printouts. Only one assistant was in at the moment, a young man, handsome, in a conservative suit. His nameplate read Martin Coyle. His area was the most ordered—even the many books behind him were arranged in descending order of size, Sachs was amused to see.

“Andrew.” He nodded a greeting to his boss, ignoring the officers as soon as he noted that they hadn’t been introduced. “Your phone messages are on your computer.”

“Thank you.” Sterling glanced at the other desk. “Jeremy’s going to look over the restaurant for the press junket?”

“He did that this morning. He’s running some papers over to the law firm. About that other matter.”

Sachs marveled that Sterling had two personal assistants—apparently one for the inside work, the other handling out-of-the-office matters. At the NYPD detectives shared, if they had help at all.

They continued on to Sterling’s own office, which wasn’t much bigger than any other she’d seen in the company. And its walls were free of decoration. Despite the SSD logo of the voyeuristic window in the watchtower, Andrew Sterling’s were curtained, cutting off what would be a magnificent view of the city. A ripple of claustrophobia coursed through her.

Sterling sat in a simple wooden chair, not a leather swivel throne. He gestured them into similar ones, though padded. Behind him were low shelves filled with books but, curiously, they were stacked with spines facing up, not outward. Visitors to his office couldn’t see his choice of reading matter without walking past the man and looking down or pulling out a volume.

The CEO nodded at a pitcher and a half dozen inverted glasses. “That’s water. But if you’d like some coffee or tea, I can have some fetched.”

Fetched? She didn’t think she’d ever heard anyone actually use the word.

“No, thank you.”

Pulaski shook his head.

“Excuse me. Just one moment.” Sterling picked up his phone, dialed. “Andy? You called.”

Sachs deduced from the tone that it was someone close to him, though it was clearly a business call about a problem of some sort. Yet Sterling spoke emotionlessly. “Ah. Well, you’ll have to, I think. We need those numbers. You know, they’re not sitting on their hands. They’ll make a move any day now… Good.”

He hung up and noticed Sachs watching him closely. “My son works for the company.” A nod at a photo on his desk, showing Sterling with a handsome, thin young man who resembled the CEO. Both were wearing SSD T-shirts at some employee outing, maybe one of the inspirational retreats. They were next to each other but there was no physical contact between them. Neither was smiling.

So one question about his personal life had been answered.

“Now,” he said, turning his green eyes on Sachs, “what’s this all about? You mentioned some crime.”

Sachs explained, “There’ve been several murders in the past few months in the city. We think that someone might’ve used information in your computers to get close to the victims, kill them and then used that and other information to frame innocent people for the crimes.”!!!The man who knows everything…

“Information?” His concern seemed genuine. He was perplexed too, though. “I’m not sure how that could happen but tell me more.”

“Well, the killer knew exactly what personal products the victims used and he planted traces of them as evidence at an innocent person’s residence to connect them to the killing.” From time to time the eyebrows above Sterling’s emerald irises narrowed. He seemed genuinely troubled as she gave him the details about the theft of the painting and coins and the two sexual assaults.

“That’s terrible…” Troubled by the news, he glanced away from her. “Rapes?”

Sachs nodded grimly and then explained how SSD seemed to be the only company in the area that had access to all the information the killer had used.

He rubbed his face, nodding slowly.

“I can see why you’re concerned… But wouldn’t it be easier for this killer just to follow the people he victimized and find out what they bought? Or even hack into their computers, break into their mailboxes, their homes, jot down their license plate numbers from the street?”

“But see, that’s the problem: He could. But he’d have to do all of those things to get the information he needed. There’ve been four crimes at a minimum—we think there could probably be more—and that means up-to-date information on the four victims and four men he’s setting up. The most efficient way to get that information would be to go through a data miner.”

Sterling gave a smile, a delicate wince.

Sachs frowned and cocked her head.

He said, “Nothing wrong with that term, ‘data miner.’ The press has latched on to it and you see it everywhere.”!!!Twenty million search-engine hits…

“But I prefer to call SSD a knowledge service provider—a KSP. Like an Internet service provider.”

Sachs had a strange sensation; he seemed almost hurt by what she’d said. She wanted to tell him she wouldn’t do it again.

Sterling smoothed a stack of papers on his organized desktop. At first she thought they were blank but then she noticed they were all turned facedown. “Well, believe me, if anyone at SSD is involved, I want to find out as much as you do. This could look very bad for us—knowledge service providers haven’t been doing very well in the press or in Congress lately.”

“First of all,” Sachs said, “the killer would have bought most of the items with cash, we’re pretty sure.”

Sterling nodded. “He wouldn’t want to leave any trace of himself.”

“Right. But the shoes he bought mail order or online. Would you have a list of people who bought these shoes in these sizes in the New York area?” She handed him a list of the Altons, the Bass and the Sure-Tracks. “The same man would have bought all of them.”

“What time period?”

“Three months.”

Sterling made a phone call. He had a brief conversation and no more than sixty seconds later he was looking at his computer screen. He swiveled it so Sachs could see, though she wasn’t sure what she was looking at—strings of product information and codes.

The CEO shook his head. “Roughly eight hundred Altons sold, twelve hundred Bass, two hundred Sure-Tracks. But no one person bought all three. Or even two pairs.”

Rhyme had suspected that the killer, if he used information from SSD, would cover his tracks but they’d hoped this lead would pay off. Staring at the numbers, she wondered if the killer had used the identity-theft techniques he’d perfected on Robert Jorgensen to order the shoes.

“Sorry.”

She nodded.

Sterling uncapped a battered silver pen and pulled a notepad toward him. In precise script he wrote several notes Sachs couldn’t read, stared at it, nodded to himself. “You’re thinking, I’d imagine, that the problem is an intruder, an employee, one of our customers or a hacker, right?”

Ron Pulaski glanced at Sachs and said, “Exactly.”

“All right. Let’s get to the bottom of it.” He checked his Seiko watch. “I want some other people in here. It may take a few minutes. We have our Spirit Circles every Monday around this time.”

“Spirit Circles?” Pulaski asked.

“Inspirational team meetings by the group leaders. They should be finished soon. We start at eight on the dot. But some go a little longer than others. Depending on the leader.” He said, “Command, intercom, Martin.”

Sachs laughed to herself. He was using the same sort of voice-recognition system that Lincoln Rhyme had.

“Yes, Andrew?” The voice came from a tiny box on the desk.

“I want Tom—security Tom—and Sam. Are they in Spirit Circles?”

“No, Andrew, but Sam’s probably going to be in Washington all week. He won’t be back till Friday. Mark, his assistant’s in.”

“Him, then.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Command, intercom, disconnect.” To Sachs he said, “Should just be a moment.”

She imagined that when Andrew Sterling summoned you, you materialized pretty quickly. He jotted a few more notes. As he did, she glanced at the company logo on the wall. When he was through writing she said, “I’m curious about that. The tower and the window. What’s the significance of it?”

“On one level it just means observing data. But there’s a second meaning.” He smiled, pleased to be explaining this. “Do you know the concept of the broken window in social philosophy?”

“No.”

“I learned about it years ago and never forgot it. The thrust is that in order to improve society you should concentrate on the small things. If you control those—or fix them—then the bigger changes will follow. Take housing projects with a high-crime problem. You can sink millions into increased police patrols and security cameras but if the projects still look dilapidated and dangerous, they’ll stay dilapidated and dangerous. Instead of millions of dollars, put thousands into fixing the windows, painting, cleaning the halls. It may seem cosmetic but people will notice. They’ll take pride in where they live. They’ll start to report people who are threats and who don’t look after their property.

“As I’m sure you know, that was the thrust of crime prevention in New York in the nineties. And it worked.”

“Andrew?” came Martin’s voice from the intercom. “Tom and Mark are here.”

Sterling ordered, “Send them in.” He set the paper he’d been jotting notes on directly in front of him. He gave Sachs a grim smile. “Let’s see if anybody’s been peeking through our window.”

ePub

ePub A4

A4