Part 3

S

he doesn't want to go back to the club, she wants to go home, but she has to go back to hand over the fifty francs, and then there's another man, another cocktail, more questions about Brazil, a hotel, another shower (this time, no comment), back to the bar where the owner takes his commission and tells her she can go, there aren't many customers tonight. She doesn't get a taxi, she walks the length of Rue de Berne, looking at the other clubs, at the shop windows full of clocks and watches, at the church on the corner (closed, always closed ...) As usual, no one looks at her.She walks through the cold. She isn't aware of the freezing temperatures, she doesn't cry, she doesn't think about the money she has earned, she is in a kind of trance.

Some people were born to face life alone, and this is neither good nor bad, it is simply life. Maria is one of those people. She begins to try and think about what has happened: she only started work today and yet she already considers herself a professional; it's as if she started ages ago, as if she had done this all her life. She experiences a strange sense of pride; she is glad she didn't run away. Now she just has to decide whether or not to carry on. If she does carry on, then she will make sure she is the best, something she has never been before.

But life was teaching her - very fast - that only the strong survive. To be strong, she must be the best, there's no alternative.

From Maria's diary a week later:

I'm not a body with a soul, I'm a soul that has a visible part called the body. All this week, contrary to what one might expect, I have been more conscious of the presence of this soul than usual. It didn't say anything to me, didn't criticise me or feel sorry for me: it merely watched me. Today, I realised why this was happening: it's been such a long time since I thought about love or anything called love. It seems to be running away from me, as if it wasn't important any more and didn't feel welcome. But if I don't think about love, I will be nothing.

When I went back to the Copacabana the second night, I was treated with much more respect -

apparently, a lot of girls do it for one night, but can't bear to go on. Anyone who does, becomes a kind of ally, a colleague, because she can understand the difficulties and the reasons or, rather, the absence of reasons for having chosen this kind of life.

They all dream of someone who will come along and see in them a real woman - companion, lover, friend. But they all know, from the very first moment of each new encounter, that this simply isn't going to happen.

I need to write about love. I need to think and think and write and write about love - otherwise, my soul won't survive.

However important Maria thought love was, she did not forget the advice she was given on her first night and did her best to confine love to the pages of her diary. Apart from that, she tried desperately to be the best, to earn a lot of money in as short a time as possible, to think very little and to find a good reason for doing what she was doing.

That was the most difficult part: what was the real reason?

She was doing it because she needed to. This wasn't quite true - everyone needs to earn money, but not everyone chooses to live on the margins of society. She was doing it because she wanted to experience something new. No, that wasn't true either; the world was full of new experiences - like skiing or going sailing on Lake Geneva, for example - but she had never been interested. She was doing it because she had nothing to lose, because her life was one of constant, day-to-day frustration.

No, none of these answers was true, so it was best to forget all about it and simply deal with whatever lay along her particular path. She had a lot in common with the other prostitutes, and with all the other women she had known in her life, whose greatest dream was to get married and have a secure life. Those who didn't think like this either had a husband (almost a third of her colleagues were married)

or were recently divorced. Because of that, and in order to understand herself, she tried - as tactfully as possible - to understand why her colleagues had chosen this profession.

She heard nothing new, but she made a list of their responses. They said they had to help out their husband (wasn't he jealous? What if one of her husband's friends came to the club one night? But Maria didn't dare to ask these questions), that they wanted to buy a house for their mother (her own excuse, apparently so noble, and the most common one), to earn enough money for their fare home (Colombians, Thais, Peruvians, Brazilians all loved this reason, even though they had earned enough money several times over and had immediately spent it, afraid to realise their dream), to have fun (this didn't really tally with the atmosphere in the club, and always rang false), they couldn't find any other kind of work (this wasn't a good reason either, Switzerland was full of jobs for cleaners, drivers and cooks).

None of them came up with any valid reason, and so she stopped trying to explain her particular Universe.

She saw that the owner, Milan, was quite right: no one ever again offered her a thousand Swiss francs for the privilege of spending a few hours with her. On the other hand, no one ever complained when she asked for three hundred and fifty francs, as if they already knew or only asked in order to humiliate her, or wanted to avoid any unpleasant surprises.

One of the girls said:

'Prostitution isn't like other businesses: beginners earn more and the more experienced earn less. Always pretend you're a beginner.'

Maria still didn't know who the 'special clients' were;

they had only been mentioned on the first night and no one ever spoke of them. Gradually, she picked up the most important tricks of the trade, like never asking personal questions, smiling a lot and talking as little as possible, never arranging to meet anyone outside the club. The most important piece of advice, however, came from a Filipino woman called Nyah:

'When your client comes, you must always groan as if you were having an orgasm too. That guarantees customer loyalty.'

'But why? They're just paying for their own satisfaction.'

'No, that's where you're wrong. A man doesn't prove he's a man by getting an erection. He's only a real man if he can pleasure a woman. And if he can pleasure a prostitute, he'll think he's the best lover on the block.'

And so six months passed: Maria learned all the necessary lessons, for example, how the Copacabana worked. Since it was one of the most expensive places in Rue de Berne, the clientele was largely made up of executives, who had permission to get home late because they were out 'having supper with clients', but these 'suppers' could never last longer than eleven o'clock at night. Most of the prostitutes who worked there were aged between eighteen and twentytwo and they stayed, on average, for two years, when they would be replaced by newer recruits. They then moved to the Neon, then to the Xenium, and the price went down as the woman's age went up, and the hours of work grew fewer and fewer. They almost all ended up in the Tropical Extasy, who accepted women over thirty; but once they were there, they could only just earn enough to pay for their lunch and their rent by going with one or two students a day (the average fee per client was just about enough to buy a bottle of cheap wine). She went to bed with many men. She didn't care how old they were or how they were dressed, but whether she said yes or no depended on how they smelled. She had nothing against cigarettes, but she hated cheap aftershave or those who didn't wash or whose clothes stank of booze.

The Copacabana was a quiet place, and Switzerland was possibly the best country in the world in which to work as a prostitute, as long as you had a residence permit and a work permit, kept all your papers in order and paid your social security; Milan was always saying that he didn't want his children to see his name in the tabloid newspapers, and so he was as strict as a policeman when it came to keeping an eye on his 'employees'.

Once you had got past the barrier of the first or second night, it was a profession much like any other, in which you worked hard, fought off the competition, tried to maintain standards, put in the necessary hours, got a bit stressed out, complained about your workload, and rested on Sundays.

Most of the prostitutes had some kind of religious faith, and attended their respective churches and masses, said their prayers and had their encounters with God.

Maria, however, was struggling in the pages of her diary not to lose her soul. She discovered, to her surprise, that one in every five clients didn't want her in order to have sex, but simply to talk a little. They paid for the bar tab and the hotel room, and when the moment came for them both to take off their clothes, the man would say, no, that won't be necessary. They wanted to talk about the pressures of work, about their unfaithful wife, about how lonely they felt, how they had no one to talk to (something she knew about all too well).

At first, she found this very odd. Then, one night, she went to the hotel with an arrogant Frenchman, a headhunter for top executive jobs (he told her this as if he were telling her the most fascinating thing in the world), and this is what he said:

'Do you know who the loneliest person in the world is? The executive with a successful career, earning an enormous salary, trusted by those above and below him, with a family to go on holiday with and children who he helps out with their homework, but who is then approached by someone like me and asked the following question: “How would you like to change your job and earn twice as much?”

'The executive, who has every reason to feel wanted and happy, becomes the most miserable creature on the planet. Why? Because he has no one to talk to. He is tempted to accept my offer, but he can't talk about it to his work colleagues because they would do everything they could to persuade him to stay. He can't talk about it to his wife, who has been his companion in his rise up the ladder of success and understands a great deal about security, but nothing about taking risks. He can't talk to anyone about it and there he is confronted by the biggest decision of his life. Can you imagine how that man feels?'

No, that man wasn't the loneliest person in the world.

Maria knew the loneliest person on the face of this Earth: herself. Nevertheless, she agreed with her client, hoping to get a big tip, which she did. But his words made her realise that she needed to find some way of freeing her clients from the enormous pressure they all seemed to be under; this meant both improving the quality of her services and the chance of earning some extra money.

When she realised that releasing tension in the soul could be as lucrative as releasing tension in the body, if not more lucrative, she started going to the library again.

She began asking for books about marital problems, psychology and politics; the librarian was delighted to see that the young woman of whom she had grown so fond had stopped thinking about sex and was now concentrating on more important matters. Maria became a regular reader of newspapers, especially, where possible, the financial pages, because the majority of her clients were business executives. She sought out self-help books, because her clients nearly all asked for her advice. She read studies of the human emotions, because all her clients were in some kind of emotional pain. Maria was a respectable, rather unusual prostitute, and after six months, she had acquired a large, faithful, very select clientele, thus arousing the envy and jealousy, but also the admiration, of her colleagues.

As for sex, it had as yet added nothing to her life: it was just a matter of opening her legs, asking them to use a condom, moaning a bit in the hope of getting a better tip (thanks to the Filipino woman, Nyah, she had learned that moaning could earn her another fifty francs), and taking a shower afterwards, hoping that the water would wash her soul clean. Nothing out of the ordinary and no kissing. For a prostitute, the kiss was sacred. Nyah had taught her to keep her kisses for the love of her life, just like in the story of Sleeping Beauty; a kiss that would waken her from her slumbers and return her to the world of fairy tales, in which Switzerland was once more the country of chocolate, cows and clocks.

And no orgasms either, no pleasure or excitement. In her search to be the very best, Maria had watched a few porn movies, hoping to pick up tips for her work. She had seen a lot of interesting things, but had preferred not to try any of them out on her clients because they took too long, and Milan was happiest when the women averaged three men a night. By the end of the six months, Maria had sixty thousand Swiss francs in a bank account; she ate in better restaurants, had bought a TV (she never watched it, but she liked to have it there) and was now seriously considering moving to a better apartment. Although she could easily afford to buy books, she continued going to the library, which was her bridge to the real world, a more solid and enduring world. She enjoyed chatting to the librarian, who was happy because Maria had perhaps found a boyfriend and a job, although she never asked, the Swiss being naturally shy and discreet (a complete fallacy, because in the Copacabana and in bed, they were as uninhibited, joyful or neurotic as any other nationality).

From Maria's diary, one warm Sunday evening:

All men, tall or short, arrogant or unassuming, friendly or cold, have one characteristic in common: when they come to the club, they are afraid. The more experienced amongst them hide their fear by talking loudly, the more inhibited cannot hide their feelings and start drinking to see if they can drive the fear away. But I am convinced that, with a few very rare exceptions - the 'special clients' to whom Milan has not yet introduced me - they are all afraid.

Afraid of what? I'm the one who should be shaking. I'm the one who leaves the club and goes off to a strange hotel, and I'm not the one with the superior physical strength or the weapons. Men are very strange, and I don't just mean the ones who come to the Copacabana, but all the men I've ever met.

They can beat you up, shout at you, threaten you, and yet they're scared to death of women really. Perhaps not the woman they married, but there's always one woman who frightens them and forces them to submit to her caprices. Even if it's their own mother.

appear confident, as if they were in perfect control of the world and of their own lives; Maria, however, could see in their eyes that they were afraid of their wife, the feeling of panic that they might not be able to get an erection, that they might not seem manly enough even to the ordinary prostitute whom they were paying for her services. If they went to a shop and didn't like the shoes they had bought, they would be quite prepared to go back, receipt in hand, and demand a refund. And yet, even though they were paying for some female company, if they didn't manage to get an erection, they would be too ashamed ever to go back to the same club again because they would assume that all the other women there would know.

'I'm the one who should feel ashamed for being unable to arouse them, but, no, they always blame themselves.'

To avoid such embarrassments, Maria always tried to put men at their ease, and if someone seemed drunker or more fragile than usual, she would avoid full sex and concentrate instead on caresses and masturbation, which always seemed to please them immensely, absurd though this might seem, since they could perfectly well masturbate on their own.

She had to make sure that they didn't feel ashamed. These men, so powerful and arrogant at work, constantly having to deal with employees, customers, suppliers, prejudices, secrets, posturings, hypocrisy, fear and oppression, ended their day in a nightclub and they didn't mind spending three hundred and fifty Swiss francs to stop being themselves for a night.

'For a night? Now come on, Maria, you're exaggerating.

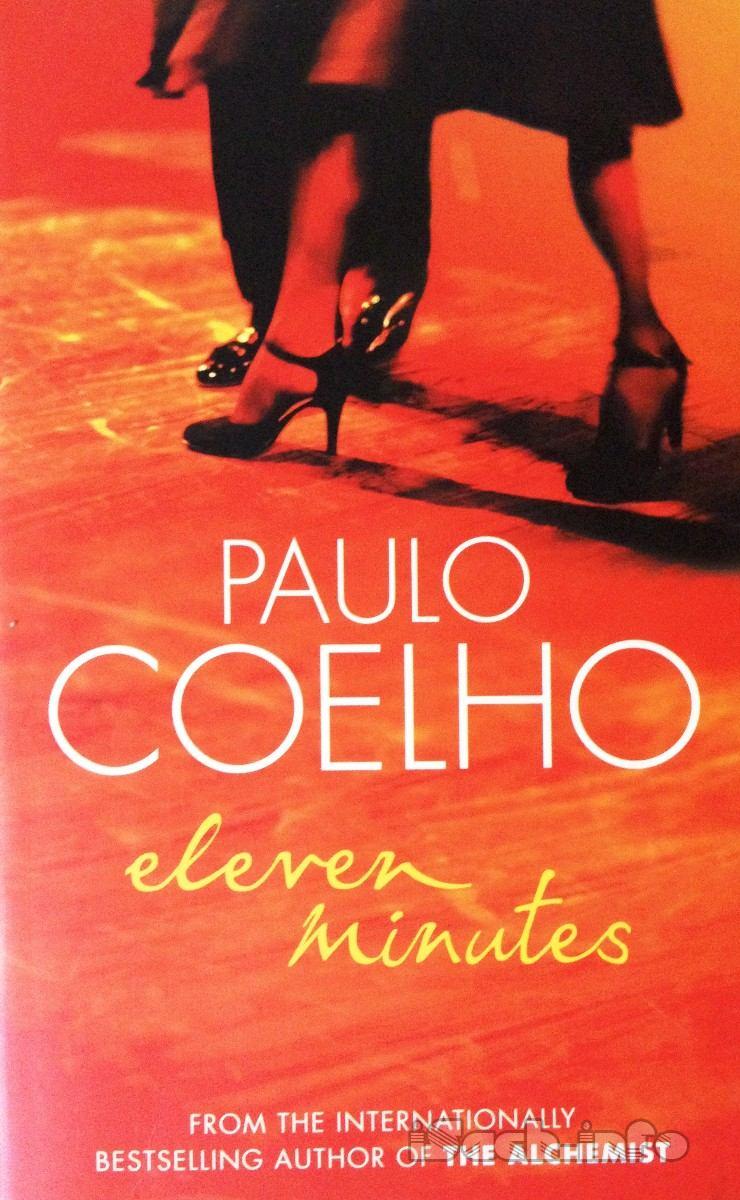

It's really only forty-five minutes, and if you allow time for taking off clothes, making some phoney gesture of affection, having a bit of banal conversation and getting dressed again, the amount of time spent actually having sex is about eleven minutes.'

Eleven minutes. The world revolved around something that only took eleven minutes.

And because of those eleven minutes in any one twentyfour-hour day (assuming that they all made love to their wives every day, which is patently absurd and a complete lie) they got married, supported a family, put up with screaming kids, thought up ridiculous excuses to justify getting home late, ogled dozens, if not hundreds of other women with whom they would like to go for a walk around Lake Geneva, bought expensive clothes for themselves and even more expensive clothes for their wives, paid prostitutes to try to give them what they were missing, and thus sustained a vast industry of cosmetics, diet foods, exercise, pornography and power, and yet when they got together with other men, contrary to popular belief, they never talked about women. They talked about jobs, money and sport.

Something was very wrong with civilisation, and it wasn't the destruction of the Amazon rainforest or the ozone layer, the death of the panda, cigarettes, carcinogenic foodstuffs or prison conditions, as the newspapers would have it. It was precisely the thing she was working with: sex.

But Maria wasn't there to save humanity, but to increase her bank balance, survive another six months of solitude and another six months of the choice she had made, send a regular monthly sum of money to her mother (who was thrilled to learn that the earlier absence of money had been due to the Swiss post, so much less efficient than the Brazilian postal system), and to buy all the things she had always dreamed of and never had. She moved to a much better apartment, with central heating (although the summer had already arrived), and from her window she could see a church, a Japanese restaurant, a supermarket and a very nice cafe, where she used to sit and read the newspapers. Otherwise, just as she had promised herself, it was a question of putting up with the same old routine: go to the Copacabana, have a drink and a dance, what do you think of Brazil, then back to his hotel, get the money up front, have a little conversation and know precisely which points to touch - on both body and soul, but mainly the soul - give some advice on personal problems, be his friend for half an hour, of which eleven minutes would be spent in opening her legs, closing her legs and pretending to moan with pleasure. Thanks very much, see you next week, you're very manly, you know, tell me how things went next time we meet, oh, that's very generous of you, but really there's no need, it's been a pleasure to spend time with you. And, above all, never fall in love. That was the most important and most sensible piece of advice that the other Brazilian woman had given her, before she disappeared, perhaps because she herself had fallen in love. Because, incredible though it may seem, in just two months of working there, Maria had had several proposals of marriage, of which at least three were serious: the director of a firm of accountants, the pilot she went with on the very first night, and the owner of a shop specialising in knives. All three had promised 'to take her away from that life' and to give her a nice house, a future, perhaps children and grandchildren.

And all for eleven minutes a day? It wasn't possible.

After her experiences at the Copacabana, she knew that she wasn't the only person who felt lonely. Human beings can withstand a week without water, two weeks without food, many years of homelessness, but not loneliness. It is the worst of all tortures, the worst of all sufferings. Like her, these men, and the many others who sought her company, were all tormented by that same destructive feeling, the sense that no one else on the planet cared about them.

In order to avoid being tempted by love, she kept her heart for her diary. She entered the Copacabana with only her body and her brain, which was growing sharper and more perceptive all the time. She had managed to persuade herself that there was some important reason why she had come to Geneva and ended up in Rue de Berne, and every time she borrowed a book from the library she was confirmed in her view that no one wrote properly about the eleven most important minutes of the day. Perhaps that was her destiny, however hard it might seem at the moment: to write a book, relating her story, her adventure.

That was it, her adventure. Although it was a forbidden word that no one dared to speak, and which most people preferred to watch on the television, in films that were shown over and over at all times of the day and night, that was what she was looking for. It was a word that evoked deserts, journeys to unknown places, idle conversations with mysterious men on a boat in the middle of a river, plane journeys, cinema studios, tribes of Indians, glaciers and Africa.

She liked the idea of a book and had even thought of a title: Eleven Minutes.

She began to put clients into three categories: the Exterminators (in homage to a film she had enjoyed hugely), who arrived stinking of drink, pretending not to look at anyone, but convinced that everyone was looking at them, dancing only briefly and then getting straight down to the business of going back to their hotel. The Pretty Woman type (again named after a film), who tried to appear elegant, gentlemanly, affectionate, as if the world depended on such kindness in order to continue turning on its axis, as if they had just been walking down the street and had come into the club by chance; they were always very sweet at first and rather uncertain when they got to the hotel, but, because of that, they always proved even more demanding than the Exterminators. And lastly, there was The Godfather type (named after yet another film), who treated a woman's body as if it were a piece of merchandise. They were the most genuine; they danced, talked, never gave tips, knew what they were buying and how much it was worth, and never let themselves be taken in by anything the woman of their choice might say. They were the only ones who, in a very subtle way, knew the meaning of the word 'Adventure'. From Maria's diary, on a day when she had her period and couldn't work:

If I were to tell someone about my life today, I could do it in a way that would make them think me a brave, happy, independent woman. Rubbish: I am not even allowed to mention the only word that is more important than the eleven minutes - love.

All my life, I thought of love as some kind of voluntary enslavement. Well, that's a lie: freedom only exists when love is present. The person who gives him or herself wholly, the person who feels freest, is the person who loves most wholeheartedly.

And the person who loves wholeheartedly feels free.

That is why, regardless of what I might experience, do or learn, nothing makes sense. I hope this time passes quickly, so that I can resume my search for myself - in the form of a man who understands me and does not make me suffer.

But what am I saying? In love, no one can harm anyone else; we are each of us responsible for our own feelings and cannot blame someone else for what we feel.

It hurt when I lost each of the various men I fell in love with. Now, though, I am convinced that no one loses anyone, because no one owns anyone.

That is the true experience of freedom: having the most important thing in the world without owning it.

Another three months passed, and autumn came, as did the date marked on the calendar: ninety days until her return journey home. Everything had happened so quickly and so slowly, she thought, realising that time exists in two different dimensions, depending on one's state of mind, but in both sorts of time her adventure was drawing to a close.

She could, of course, continue, but she could not forget the sad smile of the invisible woman who had accompanied her on that walk around the lake, telling her that things weren't that simple. However tempted she was to continue, however prepared she was for the challenges she had met on her path, all these months living alone with herself had taught her that there is always a right moment to stop something. In ninety days' time she would return to the interior of Brazil, where she would buy a small farm (she had earned rather more than she had expected), a few cows (Brazilian, not Swiss), invite her mother and father to come and live with her, take on a couple of workers, and set the business in motion. Although she believed that love is the only true experience of freedom, and that no one can possess anyone else, she still harboured a secret desire for revenge, and this formed part of her triumphal return to Brazil. After setting up the farm, she would go back to her hometown and make a large deposit in Swiss francs at the bank where the boy who had two-timed her with her best friend was working. 'Hi, how are you? Don't you remember me?' he would say. She would pretend to be trying hard to remember and would end up saying that, no, she didn't, she had just come back from a year in EU-ROPE (she would say this very slowly so that all his colleagues would hear). Or, rather, SWIT-ZER-LAND (that would sound more exotic and adventurous than France), where they have the best banks in the world.

Who was he? He would mention their schooldays. She would say: 'Ah, yes, I think I remember ...', but from her face it would be clear that she didn't. Vengeance would be hers, and then it would just be a matter of working hard, and when the farm was doing as well as she expected, she would be able to devote herself to the thing that mattered most in her life: finding her true love, the man who had been waiting for her all these years, but whom she had not yet had the chance to meet.

Maria decided to forget all about writing the book entitled Eleven Minutes. Now she needed to concentrate on the farm, on her future plans, otherwise, she would end up postponing her trip, a fatal risk.

That afternoon, she went off to meet her best - and only - friend, the librarian. She asked for a book on cattleraising and farm administration. The librarian said:

'You know, a few months ago, when you came here looking for books about sex, I began to fear for you. So many pretty young girls let themselves be seduced by the illusion of easy money, forgetting that, one day, they'll be old and will have missed out on meeting the love of their life.'

'Do you mean prostitution?'

'That's a very strong word.'

'As I said, I'm working for a company that imports and exports meat. But if I had to become a prostitute, would the consequences be so very grave if I stopped at the right moment? After all, being young inevitably means making mistakes.'

'That's what all the drug addicts say, that you just have to know when to stop. But none of them do.'

'You must have been very pretty when you were younger and you were brought up in a country that respects its inhabitants. Was that enough for you to be happy?'

'I'm proud of how I dealt with any obstacles in my life.' Should she go on, thought the librarian. Yes, why not, the girl needed to learn a bit about life.

'I had a happy childhood, I studied at one of the best schools in Berne, then I came to work in Geneva, where I met and married the man I loved. I did everything for him and he did everything for me; time passed and he retired. When he was free to do exactly what he wanted with his time, his eyes grew sadder, because he had probably never really thought about himself all his life. We never had any serious arguments or any great excitements, he was never unfaithful to me and was never rude to me in public. We lived a very ordinary life, so much so that, without a job to do, he felt useless, unimportant, and, a year later, he died of cancer.'

She was telling the truth, but felt that she might be having a negative influence on the girl standing before her.

'I still think it's best to lead a life without surprises,' she concluded. 'If we hadn't, my husband might have died even earlier, who knows.'

Maria left, determined to learn all about farming. Since she had the afternoon free, she decided to go for a stroll and, in the upper part of the city, came across a small yellow plaque bearing a drawing of a sun and an inscription:

'Road to Santiago'. What did it mean? There was a bar on the other side of the road, and since she had now learned to ask about anything she didn't understand, she resolved to go in and ask.

'I've no idea,' said the girl serving behind the bar. It was a very expensive place, and the coffee cost three times the normal price. Since she had money, though, and now that she was there, she ordered a coffee and decided to spend the next hour or so learning all there was to know about farm administration. She opened the book eagerly, but found it impossible to concentrate - it was so boring. It would be much more interesting to talk to one of her clients about it; they always knew how best to handle money. She paid for her coffee, got up, thanked the girl who had served her, left a large tip (she had invented a superstitious belief according to which the more you gave, the more you got back), went over to the door, and, without realising the importance of that moment, heard the words that would change forever her plans, her future, her farm, her idea of happiness, her female soul, her male approach to life, her place in the world.

'Hang on a moment.'

Surprised, she glanced to one side. This was a respectable bar, it wasn't the Copacabana, where men had the right to say that, although the women could always respond: 'No, I'm leaving and you can't stop me.'

She was about to ignore the remark, but her curiosity got the better of her, and she turned towards the voice. She saw a very strange scene: kneeling on the floor, with various paintbrushes scattered around him, was a long-haired young man of about thirty (or should she have said: a boy of about thirty? Her world had aged very fast), who was making a drawing of a gentleman sitting in a chair, with a glass of anisette beside him. She hadn't noticed them when she came in.

'Don't go. I've nearly finished this portrait, and I'd like to paint you as well.'

Maria replied - and as she did so, she created the link that was lacking in the universe.

'No, I'm not interested.'

'You've got a special light about you. Let me at least do a sketch.'

What was a 'sketch'? What did he mean by 'a special light'? Besides, she was vain enough to want to have her portrait painted by someone who appeared to be a serious artist. Her imagination took flight. What if he was really famous? She would be immortalised forever in a painting that would be exhibited in Paris or in Salvador da Bahia! She would become a legend!

On the other hand, what was the man doing, surrounded by all that clutter, in an expensive, perhaps usually crowded cafe?

Guessing her thoughts, the waitress said softly:

'He's a very well-known artist.'

Her intuition had been right. Maria tried not to show her feelings and to remain calm.

'He comes here now and again, and he always brings an important client with him. He says he likes the atmosphere, that it inspires him; he's doing a painting of people who represent the city. It was commissioned by the town hall.' Maria looked at the subject of the portrait. Again the waitress read her thoughts.

'He's a chemist who apparently made some really revolutionary discovery. He won the Nobel Prize.'

'Don't go,' said the painter again. 'I'll be finished in five minutes. Order what you like and put it on my bill.' As if hypnotised, she sat down at the bar, ordered an anisette (she wasn't used to drinking, and the only thing that occurred to her was to order the same as the Nobel prizewinner), and watched the man working. 'I don't represent the city, so he must be interested in something else. But he's not really my type,' she thought automatically, repeating what she always said to herself, ever since she had been working at the Copacabana; it was her salvation, her voluntary denial of the traps set by the heart. Having cleared that up, she didn't mind waiting a while - perhaps the waitress was right, perhaps this man could open doors to a world of which she knew nothing.

She watched how quickly and adroitly he put the finishing touches to his work; it was apparently a very large canvas, but it was all rolled up, and so she couldn't see what other faces he had painted. What if this was a new opportunity? The man (she had decided that he was a 'man' and not a 'boy', because otherwise she would start to feel old before her time) didn't seem the sort likely to make that kind of proposal just in order to spend the night with her. Five minutes later, as promised, he had finished his work, while Maria concentrated hard on thinking about Brazil, about her brilliant future there, and her complete lack of interest in meeting new people who might jeopardise all her plans.

'Thanks, you can move now,' said the painter to the chemist, who seemed to awaken from a dream.

And turning to Maria, he said simply:

'Sit in that corner and make yourself comfortable. The light is wonderful.'

As if everything had been ordained by fate, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, as if she had known this man all her life or had already lived this moment in dreams and now knew what to do in reality, Maria picked up her glass of anisette, her bag, and the books on farm management, and went over to the place indicated by the man - a table near the window. He brought his brushes, the large canvas, a series of small glass bottles full of various colours and a packet of cigarettes, and knelt at her feet.

'Now don't move.'

'That's asking a lot; my life is in constant motion.' Maria thought she was being terribly witty, but the man ignored her remark. Trying to appear natural, because she found the way the man looked at her most discomfiting, she pointed across the road at the plaque:

'What is the “Road to Santiago”?'

'It's a pilgrimage route. In the Middle Ages, people from all over Europe would come along this street, heading for a city in Spain, Santiago de Compostela.'

He folded over one part of the canvas and prepared his brushes. Maria still didn't know quite what to do.

'Do you mean that if I followed that street, I'd eventually get to Spain?'

'Yes, in two or three months' time. But can I just ask you a favour? Stop talking; it will only take about ten minutes. And take that package off the table.'

'They're books,' she said, slightly irritated by his authoritarian tone. She wanted him to know that he was kneeling before a cultivated woman, who spent her time in libraries not shops. But he himself picked up the package and placed it unceremoniously on the floor.

She had failed to impress him. Not, of course, that she was remotely interested in impressing him; she was off-duty now and would save her seductive powers for later, for men who would pay handsomely for her efforts. Why bother striking up a relationship with a painter who might not even have enough money to buy her a coffee? A man of thirty shouldn't wear his hair so long, it looked ridiculous. Why did she assume he had no money? The waitress had said he was wellknown, or was it just the chemist who was famous? She studied his clothes, but that didn't help; life had taught her that the men who took least care of their appearance - as with this painter - always seemed to have more money than the men in suits and ties.

'What am I doing thinking about this man? What interests me is the painting.'

Ten minutes of her time was not such a high price to pay for the chance of being immortalised in a painting. She saw that he was painting her alongside the prizewinning chemist and she began to wonder if, after all, he would want some kind of payment.

'Turn towards the window.'

Again she obeyed unquestioningly, which was not at all like her. She sat looking at the people passing by, at the plaque with the name of that road on it, thinking about how that road had been there for centuries, how it had survived progress and all the changes that had taken place in the world and in mankind. Perhaps it was a good omen, perhaps that painting would share the same fate and still be on display in a museum in the city in five hundred years' time ...

The man started drawing, and, as the work progressed, she lost that initial sense of excitement and, instead, began to feel utterly insignificant. When she had gone into the cafe, she had been a very confident woman, capable of making an extremely difficult decision - leaving a job that earned her lots of money - and taking up a still more difficult challenge - running a farm back in her own country. Now, all her feelings of insecurity about the world seemed to have resurfaced, a luxury no prostitute can allow herself.

She finally worked out why she was feeling so uncomfortable: for the first time in many months, someone was looking at her not as an object, not even as a woman, but as something she could not even comprehend; the closest she could come to putting it into words was: 'he's seeing my soul, my fears, my fragility, my inability to deal with a world which I pretend to master, but about which I know nothing'.

Ridiculous, pure fantasy. Tdlike...'

'Please, don't talk,' said the man. 'I can see your light now.'

No one had ever said anything like that to her before. 'I can see your firm breasts', 'I can see your nicely rounded thighs', 'I can see in you the exotic beauty of the tropics', or, at most, 'I can see that you want to leave this life -

let me set you up in an apartment'. She was used to comments like that, but her light? Did he mean the evening light?

'Your personal light,' he said, realising that she didn't know what he was talking about.

Her personal light. Well, how wrong could he be, that innocent painter, who obviously hadn't learned much about life in his thirty-odd years. But then, as everyone knows, women mature more quickly than men, and although Maria might not spend sleepless nights pondering her particular philosophical problems, she knew one thing: she did not have what that painter called 'light' and which she took to mean 'a special glow'. She was just like everyone else, she endured her loneliness in silence, tried to justify everything she did, pretended to be strong when she was feeling weak or weak when she was feeling strong, she had renounced love and taken up a dangerous profession, but now, as that work was coming to an end, she had plans for the future and regrets about the past, and someone like that doesn't have a 'special glow'. That must just be his way of keeping her quiet and still and happy to be there, playing the fool.

Personal light, indeed. He could have said something else, like 'you've got a lovely profile'.

How does light enter a house? Through the open windows.

How does light enter a person? Through the open door of love. And her door was definitely shut. He must be a terrible painter; he didn't understand anything.

'I've finished,' he said and started collecting up his things.

Maria didn't move. She felt like asking if she could see the painting, but that might seem rude, as if she didn't trust what he had done. Curiosity, however, got the better of her; she asked and he concurred. He had painted only her face; it looked like her, but if, one day, she had seen that painting, not knowing who the model was, she would have said that it was someone much stronger, someone full of a 'light' she didn't see reflected in the mirror.

'My name's Ralf Hart. If you like, I can buy you another drink.'

'No, thank you.'

It would seem that the encounter was now taking a sadly foreseeable turn: man tries to seduce woman.

'Two more anisettes, please,' he said, ignoring Maria's answer.

What else did she have to do? Read a boring book about farm management. Walk around the lake, as she had hundreds of times before. Or talk to someone who had seen in her a light of which she knew nothing, and on the very date marked on the calendar as the beginning of the end of her 'experience'.

'What do you do?'

That was the question she did not want to hear, the question that had made her avoid other encounters when, for one reason or another, someone had approached her (though given the natural discretion of the Swiss, this happened only rarely). What possible answer could she give?

I work in a nightclub.'

Right. An enormous load fell from her shoulders, and she was pleased with all that she had learned since she had arrived in Switzerland; ask questions (Who are the Kurds? What is the road to Santiago?) and answer (I work in a nightclub) without worrying about what other people might think.

'I have a feeling I've seen you before.'

Maria sensed that he wanted to take things further, and she savoured her small victory; the painter who, minutes before, had been giving orders and had seemed so utterly sure of what he wanted, had now gone back to being a man like any other man, full of insecurity when confronted by a woman he didn't know.

'And what are those books?'

She showed them to him. Farm administration. The man seemed to grow even more insecure.

'Are you a sex worker?'

He had shown his cards. Was she dressed like a prostitute? Anyway, she needed to gain time. She was watching herself;

this was beginning to prove an interesting game, and she had absolutely nothing to lose.

'Is that all men think about?'

He put the books back in the bag.

'Sex and farm management. How very dull.'

What! It was suddenly her turn to feel put on the spot.

How dare he speak ill of her profession? He still didn't know exactly what she did, though, he was just trying out a hunch, but she had to give him an answer.

'Well, I can't think of anything duller than painting; a static thing, a movement frozen in time, a photograph that is never faithful to the original. A dead thing that is no longer of any interest to anyone, apart from painters, who are people who think they're important and cultivated, but who haven't evolved with the rest of the world. Have you ever heard of Joan Miro? Well, I hadn't until an Arab in a restaurant mentioned the name, but knowing the name didn't change anything in my life.'

She wondered if she had gone too far, but then the drinks arrived and the conversation was interrupted. They sat saying nothing for a while. Maria thought it was probably time to leave, and perhaps Ralf Hart thought the same. But before them stood those two glasses full of that disgusting drink, and that was a reason for them to continue sitting there together.

'Why the book on farm management?'

'What do you mean?'

'I've been to Rue de Berne. When you said you worked in a nightclub, I remembered that I'd seen you before in that very expensive place. I didn't think of it while I was painting, though: your “light” was so strong.'

Maria felt the floor beneath her feet give way. For the first time, she felt ashamed of what she did, even though she had no reason to; she was working to keep herself and her family. He was the one who should feel ashamed of going to Rue de Berne; all the possible charm of that meeting had suddenly vanished.

'Listen, Mr Hart, I may be a Brazilian, but I've lived in Switzerland for nine months now. I've learned that the reason the Swiss are so discreet is because they live in a very small country where almost everyone knows everyone else, as we have just discovered, which is why no one ever asks what other people do. Your remark was both inappropriate and very rude, but if your aim was to humiliate me in order to make yourself feel better, you're wasting your time. Thanks for the anisette, which is disgusting, by the way, but which I will drink to the last drop. I will then smoke a cigarette, and, finally, I'll get up and leave. But you can leave right now, if you want; we can't have famous painters sitting at the same table as a prostitute. Because that's what I am, you see. A prostitute.

I'm a prostitute through and through, from head to toe, and I don't care who knows. That's my one great virtue: I refuse to deceive myself or you. Because it's not worth it, because you don't merit a lie. Imagine if that famous chemist over there were to find out what I am.'

She began to speak more loudly.

'Yes, I'm a prostitute! And do you know what? It's set me free - knowing that I'll be leaving this godawful place in exactly ninety days' time, with loads of money, far better educated, capable of choosing a good bottle of wine, with my handbag stuffed with photographs of the snow, and knowing all there is to know about men!'

The waitress was listening, horrified. The chemist seemed not to notice. Perhaps it was just the alcohol talking, or the feeling that soon she would once more be a woman from the interior of Brazil, or perhaps it was the sheer joy of being able to say what she did and to laugh at the shocked reactions, the critical looks, the scandalised gestures.

'Do you understand, Mr Hart? I'm a prostitute through and through, from head to toe - and that's my one great quality, my virtue!'

He said nothing. He didn't even move. Maria felt her confidence returning.

'And you, sir, are a painter with no understanding of your models. Perhaps the chemist sitting over there, dozing, lost to the world, is really a railway worker. Perhaps none of the other people in your painting are what they seem. I can't understand otherwise how you could possibly say that you could see a “special light” in a woman who, as you discovered while you were painting, IS NOTHING BUT A PRO-STI-TUTE!'

These last words were spoken very slowly and loudly. The chemist woke up and the waitress brought the bill.

'This has nothing to do with you as prostitute, but with you as woman.' Ralf ignored the proffered bill and replied equally slowly, but quietly. 'You have a glow about you. The light that comes from sheer willpower, the light of someone who has made important sacrifices in the name of things she thinks are important. It's in your eyes - the light is in your eyes.'

Maria felt disarmed; he had not taken up her challenge.

She had wanted to believe that he was simply trying to pick her up. She was not allowed to think - at least not for the next ninety days - that there were interesting men on the face of the Earth.

'You see that glass of anisette before you?' he went on.

'Now, you just see the anisette. I, on the other hand, because I need to be inside everything I do, see the plant it came from, the storms the plant endured, the hand that picked the grain, the voyage by ship from another land, the smells and colours with which the plant allowed itself to be imbued before it was placed in the alcohol. If I were to paint this scene, I would paint all those things, even though, when you saw the painting, you would think you were looking at a simple glass of anisette.

'In just the same way, while you were gazing out at the street and thinking - because I know you were - about the road to Santiago, I painted your childhood, your adolescence, your lost, broken dreams, your dreams for the future, and your will - which is what most intrigues me. When you saw your portrait ...'

Maria put up her guard, knowing that it would be very difficult to lower it again later on.

'...I saw that light ... even though all that was before me was a woman who looked like you.'

Again that constrained silence. Maria looked at her watch.

'I have to go in a moment. Why did you say that sex is boring?'

'You should know that better than me.'

'I know because it's my job. I do the same thing every day. But you're a young man of thirty ...'

'Twenty-nine.'

'... young, attractive, famous, who should be interested in things like that, and who shouldn't have to go to Rue de Berne looking for company.'

'Well, I did. I went to bed with a few of your colleagues, but not because I had any problem finding female company. The problem lies with me.'

Maria felt a pang of jealousy, and was terrified. She really must leave.

'It was my last try. I've given up now,' said Ralf, starting to pick up the painting materials scattered on the floor.

'Have you got some physical problem?'

'No, I'm just not interested.' This wasn't possible.

'Pay the bill and let's go for a walk. I think a lot of people feel the same, but no one ever says so. It's good to talk to someone so honest.'

They set off along the road to Santiago, which first climbed and then descended down to the river, then to the lake, then on to the mountains, to end in some distant place in Spain. They passed people going back to work after lunch, mothers with their prams, tourists taking photographs of the splendid fountain in the middle of the lake, Muslim women in their headscarves, boys and girls out jogging, all of them pilgrims in search of that mythological city, Santiago de Compostela, which might not even exist, which might be a legend in which people need to believe in order to give meaning to their lives. Along this road walked by so many people, over so many years, went that man with long hair, carrying a heavy bag full of brushes, paints, canvas and pencils, and that woman, slightly younger, with her bag full of books about farm management. It did not occur to either of them to ask why they were making that pilgrimage together, it was the most natural thing in the world; he knew everything about her, although she knew nothing about him.

Which is why she decided to ask - now that her policy was always to ask. At first, he reacted shyly, but she knew how to wheedle information out of men, and he ended up telling her that he had been married twice (a record for a twenty-nine-year-old!), had travelled widely, met kings and queens and famous actors, been to unforgettable parties. He had been born in Geneva, but had lived in Madrid, Amsterdam, New York, and in a city in the south of France, called Tarbes, which wasn't on any of the usual tourist circuits, but which he loved because it was so close to the mountains and because its inhabitants were so warm-hearted. He had been discovered as an artist when he was only twenty, when an important art dealer happened to visit a Japanese restaurant in Geneva decorated with his work. He had earned a lot of money, he was young and healthy, he could do anything, go anywhere, meet anyone he liked, he had known all the pleasures a man could know, he did what he most enjoyed doing, and yet, despite everything, fame, money, women, travel, he was unhappy, and had only one joy in his life - his work.

ePub

ePub A4

A4