Part 1

L

uke7:37-47

For I am the first and the last

I am the venerated and the despised

I am the prostitute and the saint

I am the wife and the virgin I am the mother and the daughter

I am the arms of my mother

I am barren and my children are many

I am the married woman and the spinster

I am the woman who gives birth and she

who never procreated I am the consolation for the pain of birth

I am the wife and the husband

And it was my man who created me

I am the mother of my father

I am the sister of my husband

And he is my rejected son

Always respect me For I am the shameful and the magnificent one

Hymn to Isis, third or fourth century BC, discovered in Nag Hammadi.

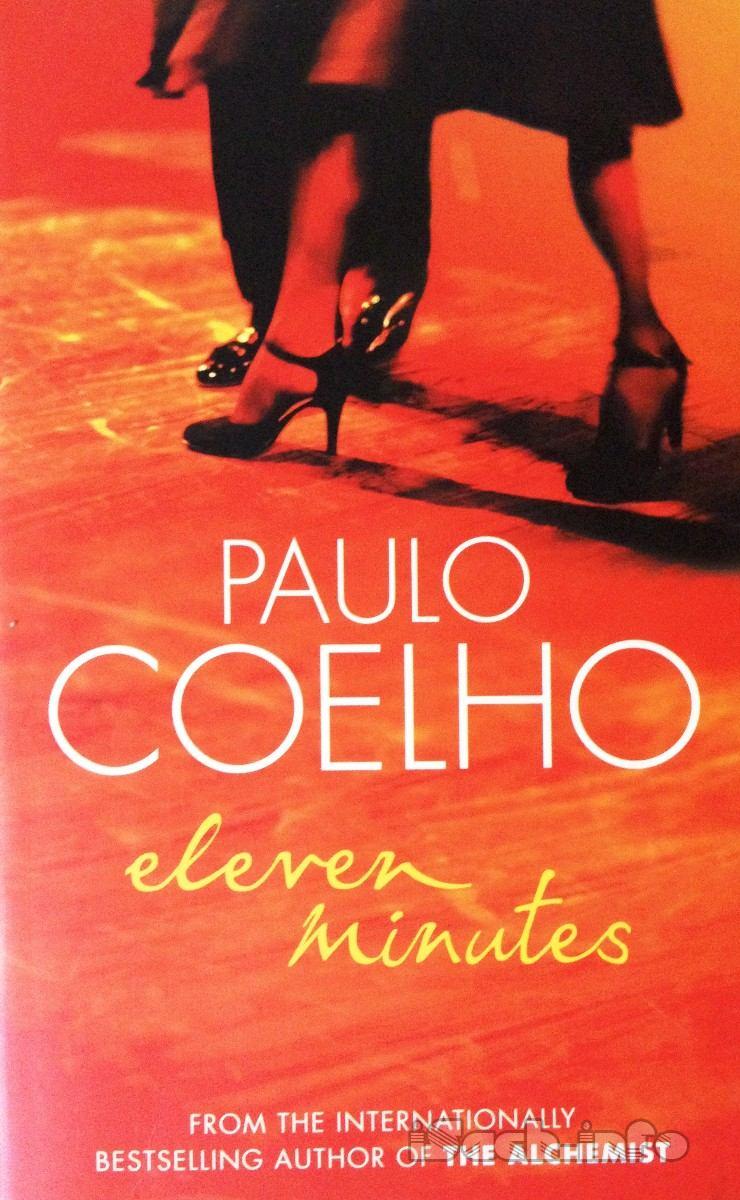

Once upon a time, there was a prostitute called Maria. Wait a minute. 'Once upon a time' is how all the best children's stories begin and 'prostitute' is a word for adults. How can I start a book with this apparent contradiction? But since, at every moment of our lives, we all have one foot in a fairy tale and the other in the abyss, let's keep that beginning.

Once upon a time, there was a prostitute called Maria. Like all prostitutes, she was born both innocent and a virgin, and, as an adolescent, she dreamed of meeting the man of her life (rich, handsome, intelligent), of getting married (in a wedding dress), having two children (who would grow up to be famous) and living in a lovely house (with a sea view). Her father was a travelling salesman, her mother a seamstress, and her hometown, in the interior of Brazil, had only one cinema, one nightclub and one bank, which was why Maria was always hoping that one day, without warning, her Prince Charming would arrive, sweep her off her feet and take her away with him so that they could conquer the world together.

While she was waiting for her Prince Charming to appear, all she could do was dream. She fell in love for the first time when she was eleven, en route from her house to school. On the first day of term, she discovered that she was not alone on her way to school: making the same journey was a boy who lived in her neighbourhood and who shared the same timetable. They never exchanged a single word, but gradually Maria became aware that, for her, the best part of the day were those moments spent going to school: moments of dust, thirst and weariness, with the sun beating down, the boy walking fast, and with her trying her hardest to keep up. This scene was repeated month after month; Maria, who hated studying and whose only other distraction in life was television, began to wish that the days would pass quickly; she waited eagerly for each journey to school and, unlike other girls her age, she found the weekends deadly dull.

Given that the hours pass more slowly for a child than for an adult, she suffered greatly and found the days far too long simply because they allowed her only ten minutes to be with the love of her life and thousands of hours to spend thinking about him, imagining how good it would be if they could talk. Then it happened.

One morning, on the way to school, the boy came up to her and asked if he could borrow a pencil. Maria didn't reply; in fact, she seemed rather irritated by this unexpected approach and even quickened her step. She had felt petrified when she saw him coming towards her, terrified that he might realise how much she loved him, how eagerly she had waited for him, how she had dreamed of taking his hand, of walking straight past the school gates with him and continuing along the road to the end, where - people said there was a big city, film stars and television stars, cars, lots of cinemas, and an endless number of fun things to do. For the rest of the day, she couldn't concentrate on her lessons, tormented by her own absurd behaviour, but, at the same time, relieved, because she knew that the boy had noticed her too, and that the pencil had just been an excuse to start a conversation, because when he came over to her, she had noticed that he already had a pen in his pocket. She waited for the next time, and during that night - and the nights that followed - she went over and over what she would say to him, until she found the right way to begin a story that would never end.

But there was no next time, for although they continued to walk to school together, with Maria sometimes a few steps ahead, clutching a pencil in her right hand, and at other times, walking slightly behind him so that she could gaze at him tenderly, he never said another word to her, and she had to content herself with loving and suffering in silence until the end of the school year.

During the interminable school holidays that followed, she woke up one morning to find that she had blood on her legs and was convinced she was going to die. She decided to leave a letter for the boy, telling him that he had been the great love of her life, and then she would go off into the bush and doubtless be killed by one of the two monsters that terrorised the country people round about: the werewolf and the mula-sem-cabega (said to be a priest's mistress transformed into a mule and doomed to wander the night). That way, her parents wouldn't suffer too much over her death, for, although constantly beset by tragedies, the poor are always hopeful, and her parents would persuade themselves that she had been kidnapped by a wealthy, childless family, but would return one day, rich and famous, while the current (and eternal) love of her life would never forget her, torturing himself each day for not having spoken to her again.

She never did write that letter because her mother came into the room, saw the bloodstained sheets, smiled and said:

'Now you're a young woman.'

Maria wondered what the connection was between the blood on her legs and her becoming a young woman, but her mother wasn't able to give her a satisfactory explanation:

she just said that it was normal, and that, from now on, for four or five days a month, she would have to wear something like a doll's pillow between her legs. Maria asked if men used some kind of tube to stop the blood going all over their trousers, and was told that this was something that only happened to women.

Maria complained to God, but, in the end, she got used to menstruating. She could not, however, get used to the boy's absence, and kept blaming herself for her own stupidity in running away from the very thing she most wanted. The day before the new term began, she went to the only church in town and vowed to the image of St Anthony that she would take the initiative and speak to the boy.

The following day, she put on her smartest dress, one that her mother had made specially for the occasion, and set off to school, thanking God that the holidays had finally ended. But the boy did not appear. And so another agonising week passed, until she found out, through some schoolfriends, that he had left town.

'He's gone somewhere far away,' someone said.

At that moment, Maria learned that certain things are lost forever. She learned too that there was a place called 'somewhere far away', that the world was vast and her own town very small, and that, in the end, the most interesting people always leave. She too would like to leave, but she was still very young. Nevertheless, looking at the dusty streets of the town where she lived, she decided that one day she would follow in the boy's footsteps. On the nine Fridays that followed, she took communion, as was the custom in her religion, and asked the Virgin Mary to take her away from there.

She grieved for a while too and tried vainly to find out where the boy had gone, but no one knew where his parents had moved to. It began to seem to Maria that the world was too large, that love was something very dangerous and that the Virgin was a saint who inhabited a distant heaven and didn't listen to the prayers of children.

Three years passed; she learned geography and mathematics, she began following the soaps on TV; at school, she read her first erotic magazine; and she began writing a diary describing her humdrum life and her desire to experience first-hand the things they told her about in class - the ocean, snow, men in turbans, elegant women covered in jewels. But since no one can live on impossible dreams especially when their mother is a seamstress and their father is hardly ever at home - she soon realised that she needed to take more notice of what was going on around her. She studied in order to get on in life, at the same time looking for someone with whom she could share her dreams of adventure.

When she had just turned fifteen, she fell in love with a boy she had met in a Holy Week procession.

She did not repeat her childhood mistake: they talked, became friends and started going to the cinema and to parties together. She also noticed that, as had happened with the first boy, she associated love more with the person's absence than with their presence: she would miss her boyfriend intensely, would spend hours imagining what they would talk about when next they met, and remembering every second they had spent together, trying to work out what she had done right and what she had done wrong.

She liked to think of herself as an experienced young woman, who had already allowed one grand passion to slip from her grasp and who knew the pain that this caused,! and now she was determined to fight with all her might for this man and for marriage, determined that he was the man for marriage, children and the house by the sea. She went to talk to her mother, who said imploringly: 'But you're still very young, my dear.' 'You got married to my father when you were sixteen.' Her mother preferred not to explain that this had been because of an unexpected pregnancy, and so she used the 'things were different then' argument and brought the matter to a close.

The following day, Maria and her boyfriend went for a walk in the countryside. They talked a little, and Maria asked if he wanted to travel, but, instead of answering the question, he took her in his arms and kissed her.

Her first kiss! How she had dreamed of that moment! And the landscape was special too - the herons flying, the sunset, the wild beauty of that semi-arid region, the sound of distant music. Maria pretended to draw back, but then she embraced him and repeated what she had seen so often on the cinema, in magazines and on TV: she rubbed her lips against his with some violence, moving her head from side to side, half-rhythmic, half-frenzied. Now and then, she felt the boy's tongue touch her teeth and thought it felt delicious. Then suddenly he stopped kissing her and asked: 'Don't you want to?'

What was she supposed to say? Did she want to? Of course she did! But a woman shouldn't expose herself in that way, especially not to her future husband, otherwise he would spend the rest of his life suspecting that she might say 'yes'tnat easily to anything. She decided not to answer.

He kissed her again, this time with rather less enthusiasm. Again he stopped, red-faced, and Maria knew that something was very wrong, but she was afraid to ask what it was. She took his hand, and they walked back to the town together, talking about other things, as if nothing had happened.

That night - using the occasional difficult word because she was sure that, one day, everything she had written would be read by someone else, and because she was convinced that something very important had happened - she wrote in her diary:

When we meet someone and fall in love, we have a sense that the whole universe is on our side. I saw this happen today as the sun went down. And yet if something goes wrong, there is nothing left! No herons, no distant music, not even the taste of his lips. How is it possible for the beauty that was there only minutes before to vanish so quickly?

" Life moves very fast. It rushes us from heaven to hell in a matter of seconds.

The following day, she talked to her girlfriends. They had all seen her going out for a walk with her future 'betrothed'. After all, it is not enough just to have a great love in your life, you must make sure that everyone know; what a desirable person you are. They were dying to know what had happened, and Maria, very full of herself, saic that the best bit was when his tongue touched her teeth, One of the other girls laughed.

'Didn't you open your mouth?'

Suddenly everything became clear - his question, his disappointment.

'What for?'

'To let him put his tongue inside.'

'What difference does it make?'

'It's not something you can explain. That's just how people kiss.'

There was much giggling, pretend pity and gleeful feelings of revenge amongst these girls who had never had a boy in love with them. Maria pretended not to care and she laughed too, although her soul was weeping. She secretly, cursed the films she had seen in the cinema, from which she had learned to close her eyes, place her hand on the man's head and move her head slightly to right and left, but which had failed to show the essential, most important thing. She made up the perfect excuse (I didn't want to give myself at once, because I wasn't sure, but now I realise that you are the love of my life) and waited for the next opportunity.

She didn't see him until three days later, at a party in a local club, and he was holding the hand of a friend of hers, the one who had asked her about the kiss. She again pretended that she didn't care, and survived until the end of the evening talking with her girlfriends about film stars and about other local boys, and pretending not to notice her friends' occasional pitying looks. When she arrived home, though, she allowed her universe to crumble; she cried all night, suffered for the next eight months and concluded that love clearly wasn't made for her and that she wasn't made for love. She considered becoming a nun and devoting the rest of her life to a kind of love that didn't hurt and didn't leave painful scars on the heart - love for Jesus. At school, they learned about missionaries who went to Africa, and she decided that there lay an escape from her dull existence. She planned to enter a convent, she learned first aid (according to some teachers, a lot of people were dying in Africa), worked harder in her religious knowledge classes, and began to imagine herself as a modern-day saint, saving lives and visiting jungles inhabited by lions and tigers.

However, her fifteenth year brought with it not only the discovery that you were supposed to kiss with your mouth open, and that love is, above all, a cause of suffering. She discovered a third thing: masturbation. It happened almost by chance, as she was touching her genitals while waiting for her mother to come home. She used to do this when she was a child and she liked the feeling, until, one day, her father saw her and slapped her hard, without explaining why. She never forgot being hit like that, and she learned that she shouldn't touch herself in front of other people;

since she couldn't do it in the middle of the street and she didn't have a room of her own at home, she forgot all about the pleasurable sensation.

Until that afternoon, almost six months after the kis Her mother was late coming home, and she had nothing to do; her father had just gone out with a friend, and since there was nothing interesting on the TV, she began examining her own body, in the hope that she might find some unwanted hair which could immediately be tweezered out. To her surprise, she noticed a small gland above her vagina. she began touching it and found that she couldn't stop; the feelings provoked were so strong and so pleasurable, an her whole body - particularly the part she was touching became tense. After a while, she began to enter a kind of paradise, the feelings grew in intensity, until she notice that she could no longer see or hear clearly, everythin appeared to be tinged with yellow, and then she moane with pleasure and had her first orgasm.

Orgasm!

It was like floating up to heaven and then parachuting slowly down to earth again. Her body was drenched in sweat, but she felt complete, fulfilled and full of energy. If that was what sex was! How wonderful! Not like in erotic magazines in which everyone talked about pleasure, but seemed to be grimacing in pain. And no need for a man who liked a woman's body, but had no time for her feelings She could do it on her own! She did it again, this time imagining that a famous movie star was touching her, and once more she floated up to paradise and parachuted down again, feeling even more energised. Just as she was about to do it for a third time, her mother came home.

Maria talked to her girlfriends about her new discovery, but saying that she had only discovered it a few hours before. All of them - apart from two - knew what she was talking about, but none of them had ever dared to raise the subject. It was Maria's turn to feel like a revolutionary, to be the leader of the group, inventing an absurd 'secret confidential game, which involved asking everyone their favourite method of masturbation. She learned various different techniques, like lying under the covers in the heat of summer (because, one of her friends assured her, sweating helped), using a goose feather to touch yourself there (she didn't yet know what the place was called), letting a boy do it to you (Maria thought this unnecessary), using the spray n the bidet (she didn't have one at home, but she would try to as soon as she visited one of her richer friends).

Anyway, once she had discovered masturbation and learned a few of the techniques suggested by her friends, she abandoned forever the idea of a religious life. Masturbation have her enormous pleasure, and yet the Church seemed to imply that sex was the greatest of sins. She heard various tales from those same girlfriends: masturbation gave you spots, could lead to madness or even pregnancy. Nevertheless, despite all these risks, she continued to pleasure herself at least once a week, usually on Wednesdays, when her father went out to play cards with his friends.

At the same time, she grew more and more insecure in her relationships with boys, and more and more determined to leave the place where she lived. She fell in love a third time and a fourth, she knew how to kiss now, and when she was alone with her boyfriends, she touched them an allowed herself to be touched, but something always wer wrong, and the relationship would end precisely at the moment when she was sure that this was the person with whom she wanted to spend the rest of her life. After a long time, she came to the conclusion that men brought on pain, frustration, suffering and a sense of time draggin One afternoon, watching a mother playing with her two year-old son, she decided that she could still think about husband, children and a house with a sea-view, but that she would never fall in love again, because love spoiled everything.

And so Maria's adolescent years passed. She grew prettier and prettier, and her sad, mysterious air brought her many suitors. She went out with one boy and with another, and dreamed and suffered - despite her promise to herself ever to fall in love again. On one such date, she lost her virginity on the back seat of a car; she and her boyfriend were touching each other with more than usual ardour, the boy got very worked up, and she, weary of being the only virgin amongst her group of friends, allowed him to penetrate her. Unlike masturbation, which took her up to eaven, this hurt her and caused a trickle of blood which left a stain on her skirt that took ages to wash out. There wasn't the magical sensation of her first kiss - the heronsying, the sunset, the music ... but she would rather not think about that.

She made love with the same boy a few more times, although she had to threaten him first, saying that if he didn't, she would tell her father he had raped her. She used im as a way of learning, trying in every way she could to understand what pleasure there was in having sex with a partner.

She couldn't understand it; masturbation was much less rouble and far more rewarding. But all the magazines, the TV programmes, books, girlfriends, everything, ABSOLUTE EVERYTHING, said that a man was essential. Maria beg; to think that she must have some unspeakable sexual problem, so she concentrated still more on her studies an for a while, forgot about that marvellous, murderous thing called Love. From Maria's diary, when she was seventeen:

My aim is to understand love. I know how alive I felt when I was in love, and I know that everything I have now, however interesting it might seem, doesn't really excite me.

But love is a terrible thing: I've seen my girlfriends suffer and I don't want the same thing to happen to me. They used to laugh at me and my innocence, but now they ask me how it is I manage men so well. I smile and say nothing, because I know that the remedy is worse than the pain: I simply don't fall in love. With each day that passes, I see more clearly how fragile men are, how inconstant, insecure and surprising they are ...a few of my girlfriends' fathers have propositioned me, but I've always refused. At first, I was shocked, but now I think it's just the way men are.

Although my aim is to understand love, and although I suffer to think of the people to whom I gave my heart, I see that those who touched my heart failed to arouse my body, and that those who aroused my body failed to touch my heart.

She turned nineteen, having finished secondary school, and earnd a job in a draper's shop, where her boss promptly fell in love with her. By then, however, Maria knew how to use a man, without being used by him. She never let him touch her, although she was always very coquettish, conscious of the power of her beauty.

The power of beauty: what must the world be like for ugly women? She had some girlfriends who no one ever invited at parties or who men were never interested in. Incredible though it might seem, these girls placed far greater value on the little love they received, suffered in immencely when they were rejected and tried to face the future looking for other things beyond getting all dressed up for someone else. They were more independent, took more interest in themselves, although, in Maria's imagination, the world for them must seem unbearable.

She knew how attractive she was, and although she rarely listened to her mother, there was one thing her mother said that she never forgot: 'Beauty, my dear, doesn't last.' With this in mind, she continued to keep her boss at arm's length, though without putting him off completely, this brought her a considerable increase in salary (she didn't know how long she would be able to string him along with the mere hope of one day getting her into bed, but at least she was earning good money meanwhile), also paid her overtime for working late (her boss liked having her around, perhaps worried that if she went out night, she might find the great love of her life). She worked for two years solidly, paid money each month to parents for her keep, and, at last, she did it! She saved enough money to go and spend a week's holiday in the place of her dreams, the place where film and TV stars live, picture postcard image of her country: Rio de Janeiro! Her boss offered to go with her and to pay all going to one of the most dangerous places in the world, one condition her mother had laid down was that she had to stay at the house of a cousin trained in judo. "

The truth was quite different: she didn't want anyone, anyone at all, to spoil what would be her first week of total freedom. She wanted to do everything - swim in the sea, speak to complete strangers, look in shop windows, and be prepared for a Prince Charming to appear and carry her off for good.

'What's a week after all?' she said with a seductive smile, hoping that she was wrong. 'It will pass in a flash, and I'll can be back at work.'

Saddened, her boss resisted at first, but finally accepted her decision, for at the time he was making secret plans to expenses, but Maria lied to him, saying that, since she >

ask her to marry him as soon as she got back, and he didn't ant to spoil everything by appearing too pushy.

aria travelled for forty-eight hours by bus, checked into a 'Besides, sir,' she said, 'you can't just leave the sAeap hotel in Copacabana (Copacabana! That beach, that without some reliable person to look after it.'

'Don't call me “sir”,' he said, and Maria saw in his face something she recognised: the flame of love. And ty ...) and even before she had unpacked her bags, she Cabbed the bikini she had bought, put it on, and despite the cloudy weather, made straight for the beach. She looked surprised her, because she had always thought he was of the sea fearfully, but ended up wading awkwardly into its interested in sex; and yet, his eyes were saying the exact opposite: 'I can give you a house, a family, some money No one on the beach noticed that this was her first your parents.' Thinking of the future, she decided to stc >ntact with the ocean, with the goddess Iemanja, the the fire. aritime currents, the foamine waves and, on the other hand, She said that she would really miss the job, as well as colleagues she just adored working with (she was careful not to mention anyone in particular, leaving the myst hanging in the air: did 'colleague' mean him?) and r aters.

No one on the beach noticed that this was her first >ntact with the ocean, with the goddess Iemanja, the aritime currents, the foaming waves and, on the other de of the Atlantic, with the coast of Africa and its lions, When she came out of the water, she was approached by a oman trying to selling wholefood sandwiches, by a ^ndsome black man who asked if she wanted to go out promised to take great care of her purse and her hondfith him that night, and by another man who didn't speak a word of Portuguese but who asked, using gestures, if she would like to have a drink of coconut water.

Maria bought a sandwich because she was too embarrassed to say 'no', but she avoided speaking to the two strangers. She felt suddenly disappointed with herself; Now that she had the chance to do anything she wanted, why is she behaving in this ridiculous manner? Finding no go explanation, she sat down to wait for the sun to come out from behind the clouds, still surprised at her own courg and at how cold the water was, even in the height of summer.

However, the man who couldn't speak Portuguj reappeared at her side bearing a drink, which he offered her. Relieved not to have to talk to him, she drank the coconut water and smiled at him, and he smiled back. After some time, they kept up this comfortable, meaningless conversation - a smile here, a smile there - until the man took a small red dictionary out of his pocket and said, ia strange accent: 'bonita' - 'pretty'. She smiled agal however much she wanted to meet her Prince Charming, 1 should at least speak her language and be slightly younger.

The man went on leafing through the little book:

'Supper ... tonight?' Then he said: 1 'Switzerland!' I And he completed this with words that sound like the bells of paradise in whatever language they are spoken:

'Work! Dollars!'

Maria did not know any restaurant called Switzerland and could things really be that easy and dreams so quick!

I filled? She erred on the side of caution: 'Thank you very much for the invitation, but I already have a job and I'm not interested in buying any dollars.'

The man, who understood not a word she said, was growing desperate; after many more smiles back and forth, he left her for a few minutes and returned with an interpreter. Through him, he explained that he was from Switzerland (the country, not a restaurant) and that he would like to have supper with her, in order to talk to her about a possible job offer. The interpreter, who introduced imself as the person in charge of foreign tourists and security in the hotel where the man was staying, added on is own account:

'I'd accept if I were you. He's an important impresario looking for new talent to work in Europe. If you like, I can put you in touch with some other people who accepted his invitation, got rich and are now married with children who don't have to worry about being mugged or unemployed.'

Then, trying to impress her with his grasp of international culture, he said:

'Besides, Switzerland makes excellent chocolates and cheeses.'

Maria's only stage experience had been in the Passion lay that the local council always put on during Holy week, and in which she had had a walk-on part as a 'aterseller. She had barely slept on the bus, but she was excited by the sea, tired of eating sandwiches, wholefood or therwise, and confused because she didn't know anyone and needed to find a friend. She had been in similar situa-

tions before, in which a man promises everything and gives nothing, so she knew that all this talk of acting was just a way of getting her interested.

However, convinced that the Virgin had presented her with this chance, convinced that she must enjoy every second of her week's holiday, and because a visit to a good restaurant would provide her with something to talk about when she went home, she decided to accept the invitation, as long as the interpreter came too, for she was already getting tired of smiling and pretending that she could understand what the foreigner was saying.

The only problem was also the gravest one: she did not have anything suitable to wear. A woman never admits to such things (she would find it easier to admit that her husband had betrayed her than to reveal the state of her wardrobe), but since she did not know these people and might well never see them again, she felt that she had nothing to lose.

'I've just arrived from the northeast and I haven't got the right clothes to wear to a restaurant.'

Through the interpreter, the man told her not to worry and asked for the address of her hotel. That evening, she received a dress the like of which she had never seen in her entire life, accompanied by a pair of shoes that must have cost as much as she earned in a year.

She felt that this was the beginning of the road she had so longed for during her childhood and adolescence in the sertao, the Brazilian backlands, putting up with the constant droughts, the boys with no future, the poor but honest town, the dull, repetitive way of life: she was ready to be transformed into the princess of the universe! A man had offered her work, dollars, a pair of exorbitantly expensive shoes and a dress straight out of a fairy tale! All she lacked was some make-up, but the receptionist at her hotel took pity on her and helped her out, first warning her not to assume that every foreigner was trustworthy or that every man in Rio was a mugger.

Maria ignored the warning, put on her gifts from heaven, spent hours in front of the mirror, regretting not having brought a camera with her in order to record the moment, only to realise that she was late for her date. She raced off, just like Cinderella, to the hotel where the Swiss gentleman was staying.

To her surprise, the interpreter told her that he would not be accompanying them.

'Don't worry about the language, what matters is whether or not he feels comfortable with you.'

'But how can he if he doesn't understand what I'm saying?'

'Precisely. You don't need to talk, it's all a question of vibes.'

Maria didn't know what 'vibes' were; where she came from, people needed to exchange words, phrases, questions and answers whenever they met. But Malison - the name of the interpreter-cum-security officer - assured her that in Rio de Janeiro and the rest of the world, things were different.

'He doesn't need to understand, just make him feel at ease. He's a widower with no children; he owns a nightclub and is looking for Brazilian women who want to work abroad. I said you weren't the type, but he insisted, saying that he had fallen in love with you when he saw you coming out of the water. He thought your bikini was lovely too.' He paused.

'But, frankly, if you want to find a boyfriend here, you'll have to get a different bikini; no one, apart from this Swiss guy, will go for it; it's really old-fashioned.' Maria pretended that she hadn't heard. Mailson went on:

'I don't think he's interested in just having a bit of a fling; he reckons you've got what it takes to become the main attraction at his club. Of course, he hasn't seen you sing or dance, but you could learn all that, whereas beauty is something you're born with. These Europeans are all the same; they come over here and imagine that all Brazilian women are really sensual and know how to samba. If he's serious, I'd advise you to get a signed contract and have the signature verified at the Swiss consulate before leaving the country.

I'll be on the beach tomorrow, opposite the hotel, if you want to talk to me about anything.'

The Swiss man, all smiles, took her arm and indicated the taxi awaiting them.

'If he has other intentions, and you have too, then the normal price is three hundred dollars a night. Don't accept any less.'

Before she could say anything, she was on her way to the restaurant, with the man rehearsing the words he wanted to say. The conversation was very simple:

'Work? Dollars? Brazilian star?'

Maria, meanwhile, was still thinking about what the interpreter-cum-security officer had said: three hundred dollars a night! That was a fortune! She didn't need to suffer for love, she could play this man along just as she had her boss at the shop, get married, have children and give her parents a comfortable life. What did she have to lose? He was old and he might die before too long, and then she would be rich - these Swiss men obviously had too much money and not enough women back home.

They said little over the meal - just the usual exchange of smiles - and Maria gradually began to understand what Maflson had meant by 'vibes'. The man showed her an album containing writing in a language that she did not know;

photos of women in bikinis (doubtless better and more daring than the one she had worn that afternoon), newspaper cuttings, garish leaflets in which the only word she recognised was 'Brazil', wrongly spelled (hadn't they taught him at school that it was written with an V?). She drank a lot, afraid that the man would proposition her (after all, even though she had never done this in her life before, no one could turn their nose up at three hundred dollars, and things always seem simpler with a bit of alcohol inside you, especially if you're among strangers). But the man behaved like a perfect gentleman, even holding her chair for her when she sat down and got up. In the end, she said that she was tired and arranged to meet him on the beach the following day (pointing to her watch, showing him the time, making the movement of the waves with her hands and saying 'a-ma-nha' - 'tomorrow' - very slowly).

He seemed pleased and looked at his own watch (possibly Swiss), and agreed on the time.

She did not go to sleep straight away. She dreamed that it was all a dream. Then she woke up and saw that it wasn't:

there was the dress draped over the chair in her modest room, the beautiful shoes and that rendezvous on the beach.

From Maria's diary, on the day that she met the Swiss man: Everything tells me that I am about to make a wrong decision, but making mistakes is just part of life. What does the world want of me? Does it want me to take no risks, to go back where I came from because I didn't have the courage to say 'yes' to life?

I made my first mistake when I was eleven years old, when that boy asked me if I could lend him a pencil; since then, I've realised that sometimes you get no second chance and that it's best to accept the gifts the world offers you. Of course it's risky, but is the risk any greater than the chance of the bus that took forty-eight hours to bring me here having an accident? If I must be faithful to someone or something, then I have, first of all, to be faithful to myself. If I'm looking for true love, I first have to get the mediocre loves out of my system. The little experience of life I've had has taught me that no one owns anything, that everything is an illusion - and that applies to material as well as spiritual things. Anyone who has lost something they thought was theirs forever (as has happened often enough to me already) finally comes to realise that nothing really belongs to them.

And if nothing belongs to me, then there's no point wasting my time looking after things that aren't mine; it's best to live as if today were the first (or last) day of my life.

The next day, together with Mailson, the interpreter-cumsecurity officer and now, according to him, her agent, she said that she would accept the Swiss man's offer, as long as she had a document provided by the Swiss consulate. The foreigner, who seemed accustomed to such demands, said that this was something he wanted too, since, if she was to work in his country, she needed a piece of paper proving that no one there could do the job she was proposing to do - and this was not particularly difficult, given that Swiss women had no particular talent for the samba. Together they went to the city centre, and the security officer-cuminterpreter-cum-agent demanded a cash advance as soon as the contract was signed, thirty per cent of the five hundred dollars she received.

'That's a week's payment in advance. One week, you understand? You'll be earning five hundred dollars a week from now on, but with no deductions, because I only get a commission on the first payment.'

Up until then, travel and the idea of going far away had just been a dream, and dreaming is very pleasant as long as you are not forced to put your dreams into practice. That way, we avoid all the risks, frustrations and difficulties, and when we are old, we can always blame other people -

preferably our parents, our spouses or our children - for our failure to realise our dreams.

Suddenly, there was the opportunity she had been so eagerly awaiting, but which she had hoped would never come! How could she possibly deal with the challenges and the dangers of a life she did not know? How could she leave behind everything she was used to? Why had the Virgin decided to go this far?

Maria consoled herself with the thought that she could change her mind at any moment; it was all just a silly game, something different to tell her friends about when she went back home. After all, she lived more than a thousand kilometres from there and she now had three hundred and fifty dollars in her purse, so if, tomorrow, she decided to pack her bags and run away, there was no way they would ever be able to track her down again.

In the afternoon following their visit to the consulate, she decided to go for a walk on her own by the sea, where she looked at the children, the volleyball players, the beggars, the drunks, the sellers of traditional Brazilian artifacts (made in China), the people jogging and exercising as a way of fending off old age, the foreign tourists, the mothers with their children, and the pensioners playing cards at the far end of the promenade. She had come to Rio de Janeiro, she had been to a five-star restaurant and to a consulate, she had met a foreigner, she had an agent, she had been given a present of a dress and a pair of shoes that no one, absolutely no one, back home could ever have afforded.

And now what?

She looked out to sea: her geography lessons told her that if she set off in a straight line, she would reach Africa, with its lions and jungles full of gorillas. However, if she headed in a slightly more northerly direction, she would end up in the enchanted kingdom known as Europe, with its Eiffel Tower, EuroDisney and Leaning Tower of Pizza. What did she have to lose? Like every Brazilian girl, she had learned to samba even before she could say 'Mama'; she could always come back if she didn't like it, and she had already learned that opportunities are made to be seized.

She had spent a lot of her life saying 'no' to things to which she would have liked to say 'yes', determined to try only those experiences she could control - certain affairs she had had with men, for example. Now she was facing the unknown, as unknown as this sea had once been to the navigators who crossed it, or so she had been told in history classes. She could always say 'no', but would she then spend the rest of her life brooding over it, as she still did over the memory of the little boy who had once asked to borrow a pencil and had then disappeared - her first love? She could always say 'no', but why not try saying 'yes' this time?

For one very simple reason: she was a girl from the backlands of Brazil, with no experience of life apart from a good school, a vast knowledge of TV soaps and the certainty that she was beautiful. That wasn't enough with which to face the world.

She saw a group of people laughing and looking at the sea, afraid to go in. Two days ago, she had felt the same thing, but now she was no longer afraid; she went into the water whenever she wanted, as if she had been born there. Wouldn't it be the same in Europe?

She made a silent prayer and again asked the Virgin Mary's advice, and seconds later, she seemed perfectly at ease with her decision to go ahead, because she felt protected. She could always come back, but she would not necessarily get another chance of a trip like this. It was worth taking the risk, as long as the dream survived the forty-eight-hour journey back home in a bus with no air conditioning, and as long as the Swiss man didn't change his mind.

She was in such good spirits that when he invited her out to supper again, she wanted to appear alluring and took his hand in hers, but he immediately pulled away, and Maria realised - with a mixture of fear and relief - that he was serious about what he said.

'Samba star!' said the man. 'Lovely Brazilian samba star! Travel next week!'

This was all well and good, but 'travel next week' was out of the question. Maria explained that she couldn't take a decision without first consulting her family. The Swiss man was furious and showed her a copy of the signed contract, and for the first time she felt afraid.

'Contract!' he said.

Even though she was determined to go home, she decided to consult her agent Mailson first; after all, he was being paid to advise her.

Mailson, however, seemed more concerned with seducing a German tourist who had just arrived at the hotel and who was sunbathing topless on the beach, convinced that Brazil was the most liberal country in the world (having failed to notice that she was the only woman on the beach with her breasts exposed and that everyone was eyeing her rather uneasily). It was very hard to get him to pay attention to what she was saying.

'But what if I change my mind?' insisted Maria.

'I don't know what's in the contract, but I suppose he might have you arrested.'

'He'd never be able to find me!'

'Exactly. So why worry?'

The Swiss man, on the other hand, having spent five hundred dollars, as well as paying out for a pair of shoes, a dress, two suppers and various fees for the paperwork at the consulate, was beginning to get worried, and so, since Maria kept insisting on the need to talk to her family, he decided to buy two plane tickets and go with her to the place where she had been born - as long as it could all be resolved in fortyeight hours and they could still travel to Europe the following week, as agreed. With a smile here and a smile there, she was beginning to understand that this was all in the documents she had signed and that, when it came to seductions, feelings and contracts, one should never play around.

It was a surprise and a source of pride to the small town to see its lovely daughter Maria arrive accompanied by a foreigner who wanted to make her a big star in Europe. The whole neighbourhood knew, and her old schoolfriends asked:

'How did it happen?'

'I was just lucky.'

They wanted to know if such things were always happening in Rio de Janeiro, because they had seen similar scenarios in TV soaps. Maria would not be pinned down, wanting to place a high value on her personal experience and thus convince her friends that she was someone special.

She and the man went to her house where he handed round leaflets, with Brasil spelled with a 'z', and the contract, while Maria explained that she had an agent now and intended following a career as an actress. Her mother, seeing the diminutive bikinis worn by the girls in the photos that the foreigner was showing her, immediately gave them back and preferred to ask no questions; all that mattered was that her daughter should be happy and rich, or unhappy, but at least rich.

'What's his name?'

'Roger.'

'Rogerio! I had a cousin called Rogerio!'

The man smiled and clapped, and they all realised that he hadn't understood a word. Maria's father said:

'He's about the same age as me.'

Her mother told him not to interfere with their daughter's happiness. Since all seamstresses talk a great deal to their customers and acquire a great deal of knowledge about marriage and love, her advice to Maria was this:

'My dear, it's better to be unhappy with a rich man than happy with a poor man, and over there you'll have far more chance of becoming an unhappy rich woman. Besides, if it doesn't work out, you can just get on the bus and come home.'

Maria might be a girl from the backlands, but she was more intelligent than her mother or her future husband imagined, and she said, simply to be provocative:

'Mama, there isn't a bus from Europe to Brazil. Besides, I want a career as a performer, I'm not looking for marriage.' Her mother gave her a look of near despair.

'If you can go there, you can always come back. Being a performer, an actress, is fine for a young woman, but it only lasts as long as your looks, and they start to fade when you're about thirty. So make the most of things now. Find someone who's honest and loving, and marry him. Love isn't that important. I didn't love your father at first, but money buys everything, even true love. And look at your father, he's not even rich!'

It was bad advice from a friend, but good advice from a mother. Forty-eight hours later, Maria was back in Rio, though not without first having made a visit, alone, to her old place of work in order to hand in her resignation and to hear the owner of the shop say:

'Yes, I'd heard that a big French impresario wanted to take you off to Paris. I can't stop you going in pursuit of your happiness, but I want you to know something before you leave.'

He took a medal on a chain out of his pocket.

'It's the Miraculous Medal of Our Lady of the Graces. She has a church in Paris, so go there and pray for her protection. Look, there are some words engraved around the Virgin.'

Maria read: 'Hail Mary conceived without sin, pray for us who turn to you. Amen.'

'Remember to say those words at least once a day. And...' He hesitated, but it was getting late.

'... if one day you come back, I'll be waiting for you. I missed my chance to tell you something very simple: I love you. It may be too late now, but I wanted you to know.' Missed chances. She had learned very early on what that meant. 'I love you', though, were three words she had often heard during her twenty-two years, and it seemed to her that they were now completely devoid of meaning, because they had never turned into anything serious or deep, never translated into a lasting relationship. Maria thanked him for his words, noted them in her memory (one never knows what life may have in store for us, and it's always good to know where the emergency exit is), gave him a chaste kiss on the cheek and left without so much as a backward glance.

They returned to Rio, and within a day she had her passport (Brazil had really changed, Roger said, using a few words in Portuguese and a lot of gestures, which Maria took to mean 'before it used to take ages'). With the help of Maflson, the security offlcer-cum-interpreter-cum-agent, any other important purchases were made (clothes, shoes, make-up, everything that a woman like her could want).

On the eve of their departure for Europe, they went to a nightclub, and when Roger saw her dance, he felt pleased with his choice; he was clearly in the presence of a future great star of Cabaret Cologny, this lovely dark girl with her pale eyes and hair as black as the wing of the grauna (the Brazilian bird often evoked by local authors to describe black hair). The work permit from the Swiss consulate was ready, so they packed their bags and, the following day, they were flying to the land of chocolate, clocks and cheese, with Maria secretly planning to make this man fall in love with her - after all, he wasn't old, ugly or poor. What more could she want?

She arrived feeling exhausted and, while still in the airport, her heart contracted with fear: she realised that she was completely dependent on the man at her side - she had no knowledge of the country, the language or the cold. Roger's behaviour changed as the hours passed; he no longer made any attempt to be pleasant, and although he had never tried to kiss her or to fondle her breasts, the look in his eyes grew more and more distant. He installed her in a small hotel, introducing her to another young Brazilian woman, a sad creature called Vivian, who would be in charge of preparing her for the work.

Vivian looked her coolly up and down, without the least show of sympathy for someone who had clearly never been abroad before. Instead of asking her how she was feeling, she got straight down to business.

ePub

ePub A4

A4