Chapter Chapter Twelve

H

e stopped in the doorway. His eyes widened until they actually seemed to be bulging from his head. There was a pile of dog droppings in the doorway of the kitchen ... and he knew from the size of the pile whose dog had been here.'Cujo,' he whispered. 'Oh my God, Cujo's gone rabid!'

He thought he heard a sound behind him and he whirled around, hair freezing up from the back of his neck. The hallway was empty except for Gary, Gary who had said the other night that Joe couldn't sic Cujo on a yelling nigger, Gary with his throat laid open all the way to the knob of his backbone.

There was no sense in taking chances. He bolted back down the hallway, skidding momentarily in Gary's blood, leaving an elongated footmark behind him. He moaned again, but when he had shut the heavy inner door he felt a little better.

He went back to the kitchen, shying his way around Gary's body, and looked in, ready to pull the kitchen hallway door shut quickly if Cujo was in there. Again he wished distractedly for the comforting weight of his shotgun over his arm.

The kitchen was empty. Nothing -moved except the curtains, stirring in a sluggish breeze which whispered through the open windows. There was a smell of dead vodka bottles. It was sour, but better than that ... that other smell. Sunlight lay on the faded hilly linoleum in orderly patterns. The phone, its once-white plastic case now dulled with the grease of many bachelor meals and cracked in some long-ago drunken stumble, hung on the wall as always.

Joe went in and closed le door firmly behind him. He crossed to the two open windows and saw nothing in the tangle of the back yard except the rusting corpses of the two cars that had predated Gary's Chrysler. He closed the windows anyway.

He went to the telephone, pouring sweat in the explosively hot kitchen. The book was hanging beside the phone on a hank of hayrope. Gary had made the hole through the book where the hayrope was threaded with Joe's drillpunch about a year ago, drunk as a lord and proclaiming that he didn't give a shit.

Joe picked the book up and then dropped it. The book thudded against the wall. His hands felt too heavy. His mouth was slimy with the taste of vomit. He got hold of the book again and opened it with a jerk that nearly tore off the cover. He could have dialed 0, or 555-1212, but in his shock he never thought of it.

The sound of his rapid, shallow breathing, his racing heart, and the riffle of the thin phonebook pages masked a faint noise from behind him: the low creak of the cellar door as Cujo nosed it open.

He had gone down cellar after killing Gary Pervier. The light in the kitchen had been too bright, too dazzling. It sent white-hot shards of agony into his decomposing brain. The cellar door had been ajar and he had padded jerkily down the stairs into the blessedly cool dark. He had fallen asleep next to Gary's old Army footlocker, and the breze from the open windows had swung the cellar door most of the way closed. The breeze had not been quite strong enough to latch the door.

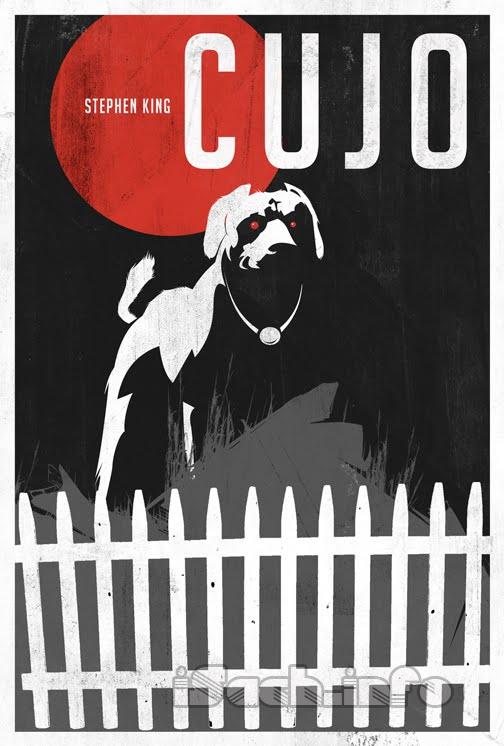

The moans, the sound of Joe retching, the thumpings and slammings as Joe ran down the hall to close the front door -these things had awakened him to his pain again. His pain and his dull, ceaseless fury. Now he stood behind Joe in the dark doorway. His head was lowered. His eyes were nearly scarlet. His thick, tawny fur was matted with gore and drying mud. Foam drizzled from his mouth in a lather, and his teeth showed constantly because his tongue was beginning to swell.

Joe had found the Castle Rock section of the book. He got the C's and ran a shaking finger down to CASTLE ROCK MUNICIPAL SERVICES in a boxed-off section halfway down one column. There was the number for the sheriffs office. He reached up a finger to begin dialing, and that was when Cujo began to growl deep in his chest.

All the nerves seemed to run out of Joe Camber's body. The telephone book slithered from his fingers and thudded against the wall again. He turned slowly toward that growling sound. He saw Cujo standing in the cellar doorway.

'Nice doggy,' he whispered huskily, and spit ran down his chin.

He made helpless water in his pants, and the sharp, ammoniac reek of it struck Cujo's nose like a keen slap. He sprang. Joe lurched to one side on legs that felt like stilts and the dog struck the wall hard enough to punch through the wallpaper and knock out plaster dust in a white, gritty puff. Now the dog wasn't growling; a series of heavy, grinding sounds escaped him, sounds more savage than any barks.

Joe backed toward the rear door. His feet tangled in one of the kitchen chairs. He pinwheeled his arms madly for balance, and might have gotten it back, but before that could happen Cujo bore down on him, a bloodstreaked killing machine with strings of foam flying backward from his jaws. There was a green, swampy stench about him.

��ob m' God lay off'n me!' Joe Camber shrieked.

He remembered Gary. He covered his throat with one hand and tried to grapple with Cujo with the other. Cujo backed off momentarily, snapping, his muzzle wrinkled back in a great humorless grin that showed teeth like a row of slightly yellowed fence spikes. Then he came again.

And this time he came for Joe Camber's balls.

'Hey kiddo, you want to come grocery shopping with me? And have lunch at Mario's?'

Tad got up. 'Yeah I Good!'

'Come on, then.'

She had her bag over her shoulder and she was wearing jeans and a faded blue shirt. Tad thought she was looking very pretty. He was relieved to see there were no sign of her tears, because when she cried, he cried. He knew it was a baby thing to do, but he couldn't help it.

He was halfway to the car and she was slipping behind the wheel when he remembered that her Pinto was all screwed UP.

'Mommy?'

'What? Get in.'

But he hung back a little, afraid. 'What if the car goes kerflooey?'

'Ker -?'She was looking at him, puzzled, and then he saw by her exasperated expression that she had forgotten all about the car being screwed up. He had reminded her, and now she was unhappy again. Was it the Pinto's fault, or was it his? He didn't know, but the guilty feeling inside said it was his. Then her face smoothed out and she gave him a crooked little smile that he knew well enough to feel it was his special smile, the one she saved just for him. He felt better.

'We're just going into town, Tadder. If Mom's ole blue Pinto packs it in, we'll just have to blow two bucks on Castle Rock's one and only taxi getting back home. Right?'

'Oh, Okay.' He got in and managed to pull the door shut.

She watched him closely, ready to move at an instant, and Tad supposed she was thinking about last Christmas, when he had shut the door on his foot and had to wear an Ace bandage for about a month. But he had been just a baby then, and now he was four years old. Now he was a big boy. He knew that was true because his dad had told him. He smiled at his mother to show her the door had been no problem, and she smiled back.

'Did it latch tight?'

'Tight,' Tad agreed, so she opened it and slammed it again, because moms didn't beheve you unless you told them something bad, like you spilled the bag of sugar reaching for the peanut butter or broke a window while trying to throw a rock all the way over the garage roof.

'Hook your belt,' she said, getting in herself again. 'When that needle valve or whatever it is messes up, the car jerks a lot.'

A little apprehensively, Tad buckled his seat belt and harness. He sure hoped they weren't going to have an accident, like in Ten-Truck Wipe Out. Even more than that, he hoped Mom wouldn't cry.

'Flaps down?' she asked, adjusting invisible goggles.

'Flaps down,' he agreed, grinning. It was just a game they played.

'Runway clear?'

'Clear.'

'Then here we go.' She keyed the ignition and backed down the driveway. A moment later they were headed for town.

After about a mile they both relaxed. Up to that point Donna had been sitting bolt upright behind the wheel and Tad had been doing the same in the passenger bucket. But the Pinto ran so smoothly that it might have popped off the assembly line only yesterday.

They went to the Agway Market and Donna bought forty dollars' worth of groceries, enough to keep them the ten days that Vic would be gone. Tad insisted on a fresh box of Twinkles, and would have added Cocoa Bears if Donna had let him. They got. shipments of the Sharp cereals regularly, but they were currently out h was a busy trip, but she still had time for bitter reflection as she waited in the checkout lane (Tad sat in the cart's child seat, swinging his legs nonchalantly) on how much three lousy bags of groceries went for these days. It wasn't just depressing; it was scary. That thought led her to the frightening possibility probability, her mind whispered - that Vic and Roger might actually lose the Sharp account and, as a result of that, the agency itself. What price groceries then?

She watched a fat woman with a lumpy behind packed into avocado-colored slacks pull a food-stamp booklet out of her purse, saw the checkout girl roll her eyes at the girl running the next register, and felt sharp rat-teeth of panic gnawing at her belly. It couldn't come to that, could it? Could it? No, of course not. Of course not. They would go back to New York first, they would

She didn't like the way her thoughts were speeding up, and she pushed the whole mess resolutely away before it could grow to avalanche size and bury her in another deep depression. Nex time she wouldn't have to buy coffee, and that would knock three bucks off the bill.

She trundled Tad and the groceries out to the Pinto and put the bags into the hatchback and Tad into the passenger bucket, standing there and listening to make sure the door latched, wanting to close the door herself but understanding it was something he felt he had to do. It was a big-boy thing. She had almost had a heart attack last December when Tad shut his foot in the door. How he had screamed! She had nearly fainted... and then Vic had been there, charging out of the house in his bathrobe, splashing out fans of driveway slush with his bare feet. And she had let him take over and be competent, which she hardly ever was in emergencies; she usually just turned to mush. He had checked to make sure the foot wasn't broken, then had changed quickly and driven them to the emergency room at the Bridgton hospital.

Groceries stowed, likewise Tad, she got behind the wheel and started the Pinto. Now it'll fuck up, she thought, but the Pinto took them docilely up the street to Mario's, which purveyed delicious pizza stuffed with enough calories to put a spare tire on a lumberjack. She did a passable job of parallel parking, ending up only eighteen inches or so from the curb, and took Tad in, feeling better than she had all day. Maybe Vic had been wrong; maybe it had been bad gas or dirt in the fuel line and it had finally worked its way out of the car's system. She hadn't looked forward to going out to Joe Camber's Garage. It was too far out in the boonies (what Vic always referred to with high good humor as East Galoshes Corners -but of course he could afford high good humor, he was a man), and she had been a little scared of Camber the one time she had met him. He was the quintessential back-country Yankee, grunting instead of talking, sullen-faced. And the dog ... what was his name? Something that sounded Spanish. Cujo, that was it. The same name William Wolfe of the SLA had taken, although Donna found it impossible to believe that Joe Camber had named his Saint Bernard after a radical robber of banks and kidnapper of rich young heiresses. She doubted if Joe Camber had ever heard of the Symbionese Liberation Army. The dog had seemed friendly enough, but it had made her nervous to see Tad patting that monster - the way it made her nervous to stand and watch him close the car door himself. Cujo looked big enough to swallow the likes of Tad in two bites.

She ordered Tad a hot pastrami sandwich because he didn't care much for pizza - kid sure didn't get that from my side of the family, she thought - and a pepperoni and onion pizza with double cheese for herself. They ate at one of the tables overlooking the road. My breath will be fit to knock over a horse, she thought. and then realised it didn't matter. She had managed to alienate both her husband and the guy who came to visit in the course of the last six weeks or so.

That brought depression cruising her way again, and once again she forced it back ... but her arms were getting a little tired.

They were almost home and Springsteen was on the radio when the Pinto started doing it again.

At first there was a small jerk. That was followed by a bigger one. She began to pump the accelerator gently; sometimes that helped.

Mommy?' Tad asked, alarmed.

It's all right, Tad,' she said, but it wasn't. The Pinto began to jerk hard, throwing them both against their seatbelts with enough force to lock the harness clasps. The engine chopped and roared. A bag fell over in the hatchback compartment, spilling cans and bottles. She heard something break.

��You goddamned shitting thing!' she cried in an exasperated fury. She could see their house just below the brow of the hill, mockingly close, but she didn't think the Pinto was going to get them there.

Frightened as much by her shout as by the car's spasms, Tad began to cry, adding to her confusion and upset and anger.

'Shut up!' she yelled at him. 'Oh Christ, just shut up, Tad!'

He began to cry harder, and his hand went to the bulge in his back pocket, where the Monster Words, folded up to packet size, were stowed away. Touching them made him feel a little bit better. Not much, but a little.

Donna decided she was going to have to pull over and stop; there was nothing else for it. She began to steer toward the shoulder, using the last of her forward motion to get there. They could use Tad's wagon to pull the groceries up to the house and then decide what to do about the Pinto. Maybe

just as the Pinto's offside wheels crunched over the sandy gravel at the edge of the road, the engine backfired twice and then the jerks smoothed out as they had done on previous occasions. A moment later she was scooting up to the driveway of the house and turning in. She drove uphill, shifted to park, pulled the emergency brake, turned off the motor, leaned over the wheel, and cried.

'Mommy?' Tad said miserably. Don't cry no more, he tried to add, but he had no voice and he could only mouth the words soundlessly, as if struck dumb by laryngitis. He looked at her only, wanting to comfort, not knowing just how it was done. Comforting her was his daddy's job, not his, and suddenly he hated his father for being somewhere else. The depth of his emotion both shocked and frightened him, and for no reason at all he suddenly saw his closet door coming open and spilling out a darkness that stank of something low and bitter.

At last she looked up, her face puffy. She found a handkerchief in her purse and wiped her eyes. 'I'm sorry, honey. I wasn't really shouting at you. I was shouting at this ... this thing.' She struck the steering wheel with her hand, hard. 'Ow!' She put the edge of her hand in her mouth and then laughed a little. It wasn't a happy laugh.

'Guess it's still kerflooey,' Tad said glumly.

'I guess it is,' she agreed, almost unbearably lonesome for Vic. 'Well, let's get the things in. We got the supplies anyway, Cisco.'

'Right, Pancho,' he said. 'I'll get my wagon.'

He brought his Redball Flyer down and Donna loaded the three bags into it, after repacking the bag that had fallen over. It had been a ketchup bottle that had shattered. You'd figure it, wouldn't you? Half a bottle of Heinz had puddled out on the powder-blue pile carpeting of the hatchback. It looked as if someone had committed hara-kiri back there. She supposed she could sop up the worst of it with a sponge, but the stain would still show. Even if she used a rug shampoo she was afraid it would show.

She tugged the wagon up to the kitchen door at the side of the house while Tad pushed. She lugged the groceries in and was debating whether to put them away or clean up the ketchup before it could set when the phone rang. Tad was off for it like a sprinter at the sound of a gun. He had gotten very good at answering the phone.

'Yes, who is it please?'

He listened, grinned, then held out the phone to her.

Figures, she thought. Someone who'll want to talk for two hours about nothing. To Tad she said, 'Do you know who it is, hon?'

'Sure,' he said. 'It's Dad.'

Her heart began to beat more rapidly. She took the phone from Tad and said, 'Hello? Vic?'

'Hi, Donna.' It was his voice all right, but so reserved ... so careful. It gave her a deep sinking feeling that she didn't need on top of everything else.

'Are you all right?' she asked.

'Sure.'

'I just thought you'd call later. If at all.

'Well, we went right over to Image-Eye. They did all the Sharp Cereal Professor spots, and what do you think? They can't find the frigging kinescopes. Roger's ripping his hair out by the roots.'

'Yes,' she said, nodding. 'He hates to be off schedule, doesn't he?'

'That's an understatement.' He sighed deeply. 'So I just thought, while they were looking . . .'

He trailed off vaguely, and her feelings of depression - her feelings of sinking -feelings that were so unpleasant and yet so childishly passive, turned to a more active sense of fear. Vic never trailed off like that, not even if he was being distracted by stuff going on at his end of the wire. She thought of the way he had looked on Thursday night, so ragged and close to the edge.

'Vic, are you all right?' She could hear the alarm in her voice and knew he must hear it too; even Tad looked up from the coloring book with which he had sprawled out on the hall floor, his eyes bright, a tight little frown on his small forehead.

'Yeah,' he said. 'I just started to say that I thought I'd call now, while they're rummaging around. Won't have a chance later tonight, I guess. How's Tad?'

'Tad's fine.'

She smiled at Tad and then tipped him a wink. Tad smiled back, the lines on his forehead smoothed out, and he went back to his coloring. He sounds tired and I'm not going to lay all that shit about the car on him, she thought, and then found herself going right ahead and doing it anyway.

She heard the familiar whine of self-pity creeping into her voice and struggled to keep it out. Why was she even telling him all of this, for heaven's sake? He sounded like he was falling apart, and she was prattling on about her Pinto's carburetor and a spilled bottle of ketchup.

'Yeah, it sounds like the needle valve, okay,' Vic said. He actually sounded a little better now. A little less down. Maybe because it was a problem which mattered so little in the greater perspective of things which they had now been forced to deal with. 'Couldn't Joe Camber get you in today?'

'I tried him but he wasn't home.'

'He probably was, though,' Vic said. 'There's no phone in his garage. Usually his wife or his kid runs his messages out to him. Probably they were out someplace.'

'Well, he still might be gone -'

'Sure,' Vic said. 'But I really doubt it, babe. If a human being could actually put down roots, Joe Camber's the guy that would do it.'

'Should I just take a chance and drive out there?' Donna asked doubtfully. She was thinking of the empty miles along 117 and the Maple Sugar Road ... and all that was before you got to Camber's road, which was so far out it didn't even have a name. And if that needle valve chose a stretch of that desolation in which to pack up for good, it would just make another hassle.

'No, I guess you better not,' Vic said. 'He's probably there ... unless you really need him. In which case he'd be gone. Catch-22.' He sounded depressed.

'Then what should I do?'

'Call the Ford dealership and tell them you want a tow.'

'But �C��

'No, you have to. If you try to drive twenty-two miles over to South Paris, it'll pack up on you for sure. And if you explain the situation in advance, they might be able to get you a loaner. Barring that, they'll lease you a car.'

'Lease ... Vic, isn't that expensive?'

'Yeah,' he said.

She thought again that it was wrong of her to be dumping all this on him. He was probably thinking that she wasn't capable of anything ... except maybe screwing the local furniture refinisher. She was fine at that. Hot salt tears, partly anger, partly self-pity, stung her eyes again. 'I'll take care of it,' she said, striving desperately to keep her voice normal, light. Her elbow was propped on the wall and one hand was over her eyes. 'Not to worry.'

'Well, I - oh, shit, there's Roger. He's dust up to his neck, but they got the kinescopes. Put Tad on for a second, would you.

Frantic questions backed up in her throat. Was it all right? Did he think it could be all right? Could they get back to go and start again? Too late. No time. She had spent the time gabbing about the car. Dumb broad, stupid quiff.

ePub

ePub A4

A4