Chapter 39~41

C

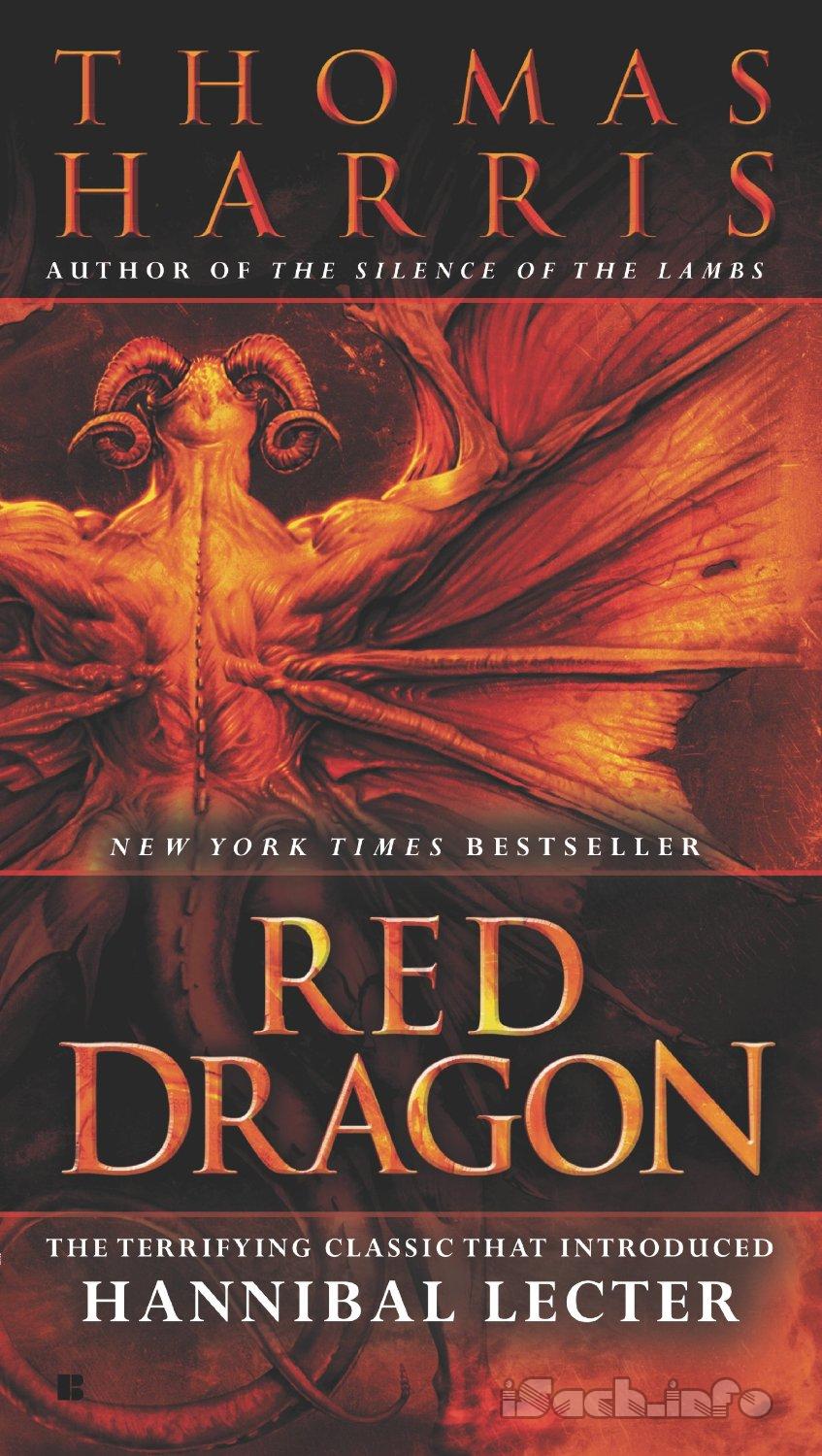

HAPTER 39Dolarhyde paid his taxi fare in front of an apartment house on Eastern Parkway two blocks from the Brooklyn Museum. He walked the rest of the way. Joggers passed him, heading for Prospect Park. Standing on the traffic island near the IRT subway station, he got a good view of the Greek Revival building. He had never seen the Brooklyn Museum before, though he had read its guidebook - he had ordered the book when he first saw "Brooklyn Museum" in tiny letters beneath photographs of The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun.

The names of the great thinkers from Confucius to Demosthenes were carved in stone above the entrance. It was an imposing building with botanical gardens beside it, a fitting house for the Dragon.

The subway rumbled beneath the street, tingling the soles of his feet. Stale air puffed from the gratings and mixed with the smell of the dye in his mustache.

Only an hour left before closing time. He crossed the street and went inside. The checkroom attendant took his valise.

"Will the checkroom be open tomorrow?" he asked.

"The museum's closed tomorrow." The attendant was a wizened woman in a blue smock. She turned away from him.

"The people who come in tomorrow, do they use the checkroom?"

"No. The museum's closed, the checkroom's closed."

Good. "Thank you."

"Don't mention it."

Dolarhyde cruised among the great glass cases in the Oceanic Hall and the Hall of the Americas on the ground floor - Andes pottery, primitive edged weapons, artifacts and powerful masks ftom the Indians of the Northwest coast.

Now there were only forty minutes left before the museum closed. There was no more time to learn the ground floor. He knew where the exits and the public elevators were.

He rode up to the fifth floor. He could feel that he was closer to the Dragon now, but it was all right - he wouldn't turn a corner and run into Him.

The Dragon was not on public display; the painting had been locked away in the dark since its return from the Tate Gallery in London.

Dolarhyde had learned on the telephone that The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun was rarely displayed. It was almost two hundred years old and a watercolor - light would fade it.

Dolarhyde stopped in front of Albert Bierstadt's A Storm in the Rocky Mountains - Mt. Rosalie 1866. From there he could see the locked doors of the Painting Study and Storage Department. That's where the Dragon was. Not a copy, not a photograph: the Dragon. This is where he would come tomorrow when he had his appointment.

He walked around the perimeter of the fifth floor, past the corridor of portraits, seeing nothing of the paintings. The exits were what interested him. He found the fire exits and the main stairs, and marked the location of the public elevators.

The guards were polite middle-aged men in thick-soled shoes, years of standing in the set of their legs. None was armed, Dolarhyde noted; one of the guards in the lobby was armed. Maybe he was a moonlighting cop.

The announcement of closing time came over the public-address system.

Dolarhyde stood on the pavement under the allegorical figure of Brooklyn and watched the crowd come out into the pleasant summer evening.

Joggers ran in place, waiting while the stream of people crossed the sidewalk toward the subway.

Dolarhyde spent a few minutes in the botanical gardens. Then he flagged a taxi and gave the driver the address of a store he had found in the Yellow Pages.

CHAPTER 40

At nine P.M. Monday Graham set his briefcase on the floor outside the Chicago apartment he was using and rooted in his pocket for the keys.

He had spent a long day in Detroit interviewing staff and checking employment records at a hospital where Mrs. Jacobi did volunteer work before the family moved to Birmingham. He was looking for a drifter, someone who might have worked in both Detroit and Atlanta or in Birmingham and Atlanta; someone with access to a van and a wheelchair who saw Mrs. Jacobi and Mrs. Leeds before he broke into their houses.

Crawford thought the trip was a waste of time, but humored him. Crawford had been right. Damn Crawford. He was right too much.

Graham could hear the telephone ringing in the apartment. The keys caught in the lining of his pocket. When he jerked them out, a long thread came with them. Change spilled down the inside of the trouser leg and scattered on the floor.

"Son of a bitch."

He made it halfway across the room before the phone stopped ringing. Maybe that was Molly trying to reach him.

He called her in Oregon.

Willy's grandfather answered the telephone with his mouth full. It was suppertime in Oregon.

"Just ask Molly to call me when she's finished," Graham told him. He was in the shower with shampoo in his eyes when the telephone rang again. He sluiced his head and went dripping to grab the receiver. "Hello, Hotlips."

"You silver-tongued devil, this is Byron Metcalf in Birmingham."

"Sorry."

"I've got good news and bad news. You were right about Niles Jacobi. He took the stuff out of the house. He'd gotten rid of it, but I squeezed him with some hash that was in his room and he owned up. That's the bad news - I know you hoped the Tooth Fairy stole it and fenced it.

"The good news is there's some film. I don't have it yet. Niles says there are two reels stuffed under the seat in his car. You still want it, right?"

"Sure, sure I do."

"Well, his intimate friend Randy's using the car and we haven't caught up with him yet, but it won't be long. Want me to put the film on the first plane to Chicago and call you when it's coming?"

"Please do. That's good, Byron, thanks."

"Nothing to it."

Molly called just as Graham was drifting off to sleep. After they assured each other that they were all right, there didn't seem to be much to say.

Willy was having a real good time, Molly said. She let Willy say good night.

Willy had plenty more to say than just good night - he told Will the exciting news: Grandpa bought him a pony.

Molly hadn't mentioned it.

CHAPTER 41

The Brooklyn Museum is closed to the general public on Tuesdays, but art classes and researchers are admitted.

The museum is an excellent facility for serious scholarship. The staff members are knowledgeable and accommodating; often they allow researchers to come by appointment on Tuesdays to see items not on public display.

Francis Dolarhyde came out of the IRT subway station shortly after 2 P.M. on Tuesday carrying his scholarly materials. He had a notebook, a Tate Gallery catalog, and a biography of William Blake under his arm.

He had a flat 9-mm pistol, a leather sap and his razor-edged fileting knife under his shirt. An elastic bandage held the weapons against his flat belly. His sport coat would button over them. A cloth soaked in chloroform and sealed in a plastic bag was in his coat pocket.

In his hand he carried a new guitar case.

Three pay telephones stand near the subway exit in the center of Eastern Parkway. One of the telephones has been ripped out. One of the others works.

Dolarhyde fed it quarters until Reba said, "Hello."

He could hear darkroom noises over her voice.

"Hello, Reba," he said.

"Hey, D. How're you feeling?"

Traffic passing on both sides made it hard for him to hear. "Okay."

"Sounds like you're at a pay phone. I thought you were home sick."

"I want to talk to you later."

"Okay. Call me late, all right?"

"I need to . . . see you."

"I want you to see me, but I can't tonight. I have to work. Will you call me?"

"Yeah. If nothing . . ."

"Excuse me?"

"I'll call."

"I do want you to come soon, D."

"Yeah. Good-bye . . . Reba."

All right. Fear trickled from his breastbone to his belly. He squeezed it and crossed the street.

Entrance to the Brooklyn Museum on Tuesdays is through a single door on the extreme right. Dolarhyde went in behind four art students. The students piled their knapsacks and satchels against the wall and got out their passes. The guard behind the desk checked them.

He came to Dolarhyde.

"Do you have an appointment?"

Dolarhyde nodded. "Painting Study, Miss Harper."

"Sign the register, please." The guard offered a pen. Dolarhyde had his own pen ready. He sigued "Paul Crane." The guard dialed an upstairs extension. Dolarhyde turned his back to the desk and studied Robert Blum's Vintage Festival over the entrance while the guard confirmed his appointment. From the comer of his eye he could see one more security guard in the lobby. Yes, that was the one with the gun.

"Back of the lobby by the shop there's a bench next to the main elevators," the desk officer said. "Wait there. Miss Harper's coming down for you." He handed Dolarhyde a pink-on-white plastic badge.

"Okay if I leave my guitar here?"

"I'll keep an eye on it."

The museum was different with the lights turned down. There was twilight among the great glass cases.

Dolarhyde waited on the bench for three minutes before Miss Harper got off the public elevator.

"Mr. Crane? I'm Paula Harper."

She was younger than she had sounded on the telephone when he called from St. Louis; a sensible-looking woman, severely pretty. She wore her blouse and skirt like a uniform.

"You called about the Blake watercolor," she said. "Let's go upstairs and I'll show it to you. We'll take the staff elevator - this way."

She led him past the dark museum shop and through a small room lined with primitive weapons. He looked around fast to keep his bearings. In the corner of the Americas section was a corridor which led to the small elevator.

Miss Harper pushed the button. She hugged her elbows and waited. The clear blue eyes fell on the pass, pink on white, clipped to Dolarhyde's lapel.

"That's a sixth-floor pass he gave you," she said. "It doesn't matter - there aren't any guards on five today. What kind of research are you doing?"

Dolarhyde had made it on smiles and nods until now. "A paper on Butts," he said.

"On William Butts?"

He nodded.

"I've never read much on him. You only see him in footnotes as a patron of Blake's. Is he interesting?"

"I'm just beginning. I'll have to go to England."

"I think the National Gallery has two watercolors he did for Butts. Have you seen them yet?"

"Not yet."

"Better write ahead of time."

He nodded. The elevator came.

Fifth floor. He was tingling a little, but he had blood in his arms and legs. Soon it would be just yes or no. If it went wrong, he wouldn't let them take him.

She led him down the corridor of American portraits. This wasn't the way he came before. He could tell where he was. It was all right.

But something waited in the corridor for him, and when he saw it he stopped dead still.

Paula Harper realized he wasn't following and turned around. He was rigid before a niche in the wall of portraits. She came back to him and saw what he was staring at. "That's a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington," she said.

No it wasn't.

"You see a similar one on the dollar bill. They call it a Lansdowne portrait because Stuart did one for the Marquis of Lansdowne to thank him for his support in the American Revolution . . . Are you all right, Mr. Crane?"

Dolarhyde was pale. This was worse than all the dollar bills he had ever seen. Washington with his hooded eyes and bad false teeth stared out of the frame. My God he looked like Grandmother. Dolarhyde felt like a child with a rubber knife.

"Mr. Crane, are you okay?"

Answer or blow it all. Get past this. My God, man, that's so sweeeet. YOU'RE THE DIRTIEST. . . No.

Say something.

"I'm taking cobalt," he said. "Would you like to sit down for a few minutes?" There was a faint medicinal smell about him.

"No. Go ahead. I'm coming."

And you are not going to cut me, Grandmother. God damn you, I'd kill you if you weren't already dead. Already dead. Already dead. Grandmother was already dead! Dead now, dead for always. My God, man, that's so sweeeet.

The other wasn't dead though, and Dolarhyde knew it

He followed Miss Harper through thickets of fear.

They went through double doors into the Painting Study and Storage Department. Dolarhyde looked around qulckly. It was a long, peaceful room, well-lighted and filled with carousel racks of draped paintings. A row of small office cubicles was partitioned off along the wall. The door to the cubicle on the far end was ajar, and he heard typing.

He saw no one but Paula Harper.

She took him to a counter-height work table and brought him a stool.

"Wait here. I'll bring the painting to you."

She disappeared behind the racks.

Dolarhyde undid a button at his belly.

Miss Harper was coming. She carried a flat black case no bigger than a briefcase. It was in there. How did she have the strength to carry the picture? He had never thought of it as flat. He had seen the dimensions in the catalogs - 17 1/8 by 13 1/2 inches - but he had paid no attention to them. He expected it to be immense. But it was small. It was small and it was here in a quiet room. He had never realized how much strength the Dragon drew from the old house in the orchard.

Miss Harper was saying something ". . . have to keep it in this solander box because light will fade it. That's why it's not on display very often."

She put the case on the table and unclasped it. A noise at the double doors. "Excuse me, I have to get the door for Julio." She refastened the case and carried it with her to the glass doors. A man with a wheeled dolly waited outside. She held the doors open while he rolled it in.

"Over here okay?"

"Yes, thank you, Julio."

The man went out.

Here came Miss Harper with the solander box.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Crane. Julio's dusting today and getting the tarnish off some frames." She opened the case and took out a white cardboard folder. "You understand that you aren't allowed to touch it. I'll display it for you - that's the rule. Okay?"

Dolarbyde nodded. He couldn't speak.

She opened the folder and removed the covering plastic sheet and mat.

There it was. The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun - the Man-Dragon rampant over the prostrate pleading woman caught in a coil of his tail.

It was small all right, but it was powerful. Stunning. The best reproductions didn't do justice to the details and the colors.

Dolarhyde saw it clear, saw it all in an instant - Blake's hand - writing on the borders, two brown spots at the right edge of the paper. It seized him hard. It was too much . . . the colors were so much stronger.

Look at the woman wrapped in the Dragon's tail. Look.

He saw that her hair was the exact color of Reba McClane's. He saw that he was twenty feet from the door. He held in voices.

I hope I didn't shock you, said Reba McClane.

"It appears that he used chalk as well as watercolor," Paula Harper was saying. She stood at an angle so that she could see what he was doing. Her eyes never left the painting.

Dolarhyde put his hand inside his shirt.

Somewhere a telephone was ringing. The typing stopped. A woman stuck her head out of the far cubicle.

"Paula, telephone for you. It's your mother."

Miss Harper did not turn her head. Her eyes never left Dolarhyde or the painting. "Would you take a message?" she said. "Tell her I'll call her back."

The woman disappeared into the office. In a moment the typing started again.

Dolarhyde couldn't hold it anymore. Play for it all, right now.

But the Dragon moved first. "I'VE NEVER SEEN-"

"What?" Miss Harper's eyes were wide.

"- a rat that big!" Dolarhyde said, pointing. "Climbing that frame!"

Miss Harper was turning. "Where?"

The blackjack slid out of his shirt. With his wrist more than his arm, he tapped the back of her skull. She sagged as Dolarhyde grabbed a handful of her blouse and clapped the chloroform rag over her face. She made a high sound once, not overloud, and went limp.

He eased her to the floor between the table and the racks of paintings, pulled the folder with the watercolor to the floor, and squatted over her. Rustling, wadding, hoarse breathing and a telephone ringing.

The woman came out of the far office.

"Paula?" She looked around the room. "It's your mother," she called. "She needs to talk to you now."

She walked behind the table. "I'll take care of the visitor if you . . ." She saw them then. Paula Harper on the floor, her hair across her face, and squatting over her, his pistol in his hand, Dolarhyde stuffing the last bite of the watercolor in his mouth. Rising, chewing, running. Toward her.

She ran for her office, slammed the flimsy door, grabbed at the phone and knocked it to the floor, scrambled for it on her hands and knees and tried to dial on the busy line as her door caved in. The lighted dial burst in bright colors at the impact behind her ear. The receiver fell quacking to the floor.

Dolarhyde in the staff elevator watched the indicator lights blink down, his gun held flat across his stomach, covered by his books.

First floor.

Out into the deserted galleries. He walked fast, his running shoes whispering on the terrazzo. A wrong turn and he was passing the whale masks, the great mask of Sisuit, losing seconds, running now into the presence of the Haida high totems and lost. He ran to the totems, looked left, saw the primitive edged weapons and knew where he was.

He peered around the corner at the lobby.

The desk officer stood at the bulletin board, thirty feet from the reception desk.

The armed guard was closer to the door. His holster creaked as he bent to rub a spot on the toe of his shoe.

If they fight, drop him first. Dolarhyde put the gun under his belt and buttoned his coat over it. He walked across the lobby, unclipping his pass.

The desk officer turned when he heard the footsteps.

"Thank you," Dolarhyde said. He held up his pass by the edges, then dropped it on the desk.

The guard nodded. "Would you put it through the slot there, please?"

The reception desk telephone rang.

The pass was hard to pick up off the glass top. The telephone rang again. Hurry.

Dolarhyde got hold of the pass, dropped it through the slot. He picked up his guitar case from the pile of knapsacks.

The guard was coming to the telephone.

Out the door now, walking fast for the botanical gardens, he was ready to turn and fire if he heard pursuit.

Inside the gardens and to the left, Dolarhyde ducked into a space between a small shed and a hedge. He opened the guitar case and dumped out a tennis racket, a tennis ball, a towel, a folded grocery sack and a big bunch of leafy celery.

Buttons flew as he tore off his coat and shirt in one move and stepped out of his trousers. Underneath he wore a Brooklyn College T-shirt and warm-up pants. He stuffed his books and clothing into the grocery bag, then the weapons. The celery stuck out the top. He wiped the handle and clasps of the case and shoved it under the hedge.

Cutting across the gardens now toward Prospect Park, the towel around his neck, he came out onto Empire Boulevard. Joggers were ahead of him. As he followed the joggers into the park, the first police cruisers screamed past. None of the joggers paid any attention to them. Neither did Dolarhyde.

He alternated jogging and walking, carrying his grocery bag and racket and bouncing his tennis ball, a man cooing off from a hard workout who had stopped by the store on the way home.

He made himself slow down; he shouldn't run on a full stomach. He could choose his pace now.

He could choose anything.

ePub

ePub A4

A4