Chapter 27

I

T WAS COLD INSIDE THE REFRIGERATOR. YOU MIGHT THINK that would be obvious, but obviousness doesn’t provide any warmth, and I had been shivering since the shock of Samantha’s betrayal wore off. It was cold, and the small room was filled with jars of blood, and there was no way out, not even with the help of my tire iron. I had tried to shatter the small glass window in the refrigerator’s door, which shows how low I had descended into panicked unreason. The glass was an inch thick and reinforced with wire, and even if I had managed to break it, the opening was barely big enough for one of my legs.Naturally enough, I had tried to call Deborah on my cell phone, and of course, more naturally, there was no reception at all inside an insulated box with thick metal walls. I knew they were thick, because after I gave up trying to break the window and then bent the tire iron trying to pry open the door, I had hammered on the walls for a few minutes, which was almost as effective as twiddling my thumbs would have been. The tire iron bent a little more, the rows and rows of blood seemed to close in on me, and I started to breathe hard—and Samantha just sat and smiled.

And Samantha herself—why did she sit there with that Mona Lisa smile of perfect contentment? She had to know that at some point in the not-too-distant future, she would become an entrée. And yet when I had arrived on my white horse in perfectly serviceable armor, she had kicked the door shut and trapped us both. Was it the drugs they had obviously fed her? Or was she so delusional that she believed they wouldn’t really do to her what they had already done to her best friend, Tyler Spanos?

Gradually, as the impulse to hammer at the walls faded and the shivering took over, I began to wonder about her more and more. She paid no attention at all to my feeble and comical efforts to break out of a giant steel box with a cheesy piece of iron—it should have been called a “tire tin” in this case—and she just smiled, eyes half-closed, even when I gave up and sat beside her and let the cold get at me and take over.

It really started to annoy me, that smile. It was the kind of expression you might see on someone who had taken too many recreational downers after making a killing in real estate; filled with a relaxed sense of complete satisfaction with herself, all she had done, and the world as she had shaped it, and I began to wish they had eaten her first.

So I sat beside her and shivered and alternated anxiety with thinking terrible thoughts about Samantha. As if she hadn’t behaved badly enough already, she didn’t even offer to share her blanket with me. I tried to shut her out—difficult to do in a small and very cold room when you are sitting right next to the thing you want to forget, but I tried.

I looked at the jars of blood. They still made me faintly queasy, but at least they took my mind off Samantha’s treachery. So much of the awful sticky stuff—I looked away, and finally found a patch of metal wall to stare at that was not filled with either blood or Samantha.

I wondered what Deborah was going to do. It was selfish of me, I know, but I hoped she was starting to get very worried about me. I had been gone just a little bit too long by now, and she would be sitting in the car and grinding her teeth together, tapping her fingers on the steering wheel, glaring at her watch, wondering if it was too soon to do something and, if not, what that something ought to be. It cheered me up a little—not just the thought that she was certainly going to do something, but that she was fretting about it, too. It served her right. I hoped she would grind her teeth so hard she needed dental work. Maybe she could see Dr. Lonoff.

For no other reason than because I was anxious and bored, I took out my cell phone and tried to call her again. It still didn’t work.

“That won’t work in here,” Samantha said in her slow and happy voice.

“Yes, I know,” I said.

“Then you should stop trying,” she said.

I know I was new to having human feelings, but I was pretty certain that the one she was inspiring in me was annoyance verging on loathing. “Is that what you’ve done?” I said. “Given up?”

She shook her head slowly with a kind of low-pitched two-syllable chuckle. “No way,” she said. “Not me.”

“Then for God’s sake, why are you doing this? Why did you trap me in here and now you just sit there and smirk?”

She turned her head toward me and I got the feeling that she actually focused on me for the first time. “What’s your name?” she asked.

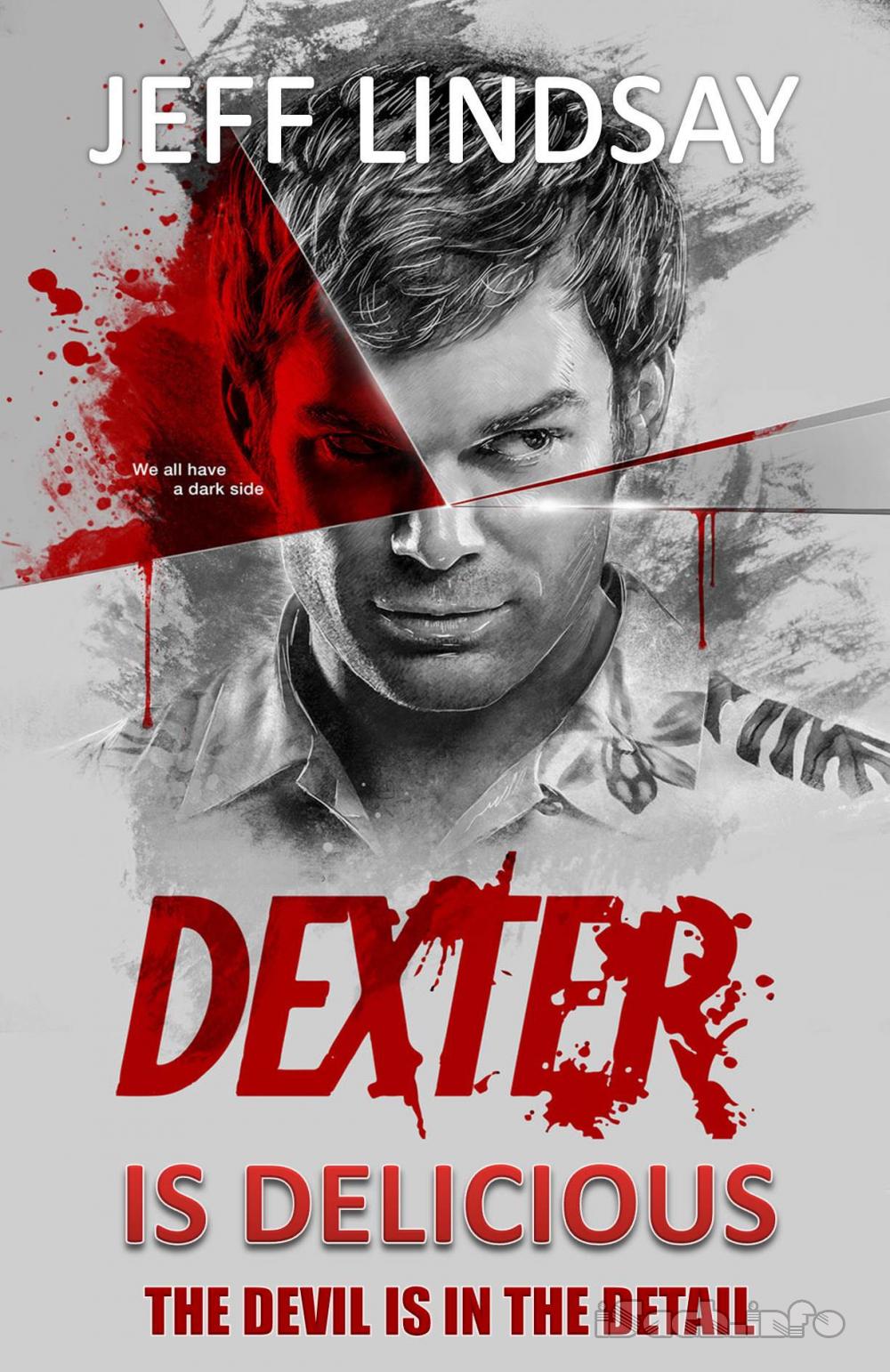

I saw no reason not to tell her—of course, I also saw no reason not to slap her, but that could wait. “Dexter,” I said. “Dexter Morgan.”

“Whoa,” she said, with another syllable of that annoying laugh. “Weird name.”

“Yes, completely bizarre,” I said.

“Anyway,” she said. “Dexter. Do you have anything in your life that you really, really want?”

“I’d like to get out of here,” I said.

She shook her head. “But something that’s, you know. Like, totally, totally, ahh … forbidden? Like, really wrong? But you want it anyway, so much it’s like—I mean, you can’t even talk about it to anybody, but it’s all you can think about sometimes?”

I thought about the Dark Passenger, and it stirred slightly as I did, as if to remind me that none of this had to happen if only I’d listened. “No, not a thing,” I said.

She looked at me for a long moment, her lips parted but still smiling. “Okay,” she said, as if she knew I was lying but it didn’t really matter. “But I have. I mean, there is something. For me.”

“It’s wonderful to have a dream,” I said. “But wouldn’t it be a lot easier to make it come true if we got out of here?”

She shook her head. “Um, no,” she said. “That’s just it. I have to be in here. Or, you know. I don’t get to—” And she bit her lip in a kind of funny way and shook her head again.

“What?” I said, and her coy act was nudging me even closer to an uncontrollable urge to rattle her teeth. “You don’t get to what?”

“It’s really hard to say, even now,” she said. “It’s kind of like …” She frowned, which was a pleasant change. “Don’t you have some kind of secret that, you know … you can’t help it, but it makes you kind of, like, ashamed?”

“Sure,” I said. “I watched a whole season of American Idol.”

“But that’s everybody,” she said, waving a hand dismissively and making a sour-lemon face. “Everybody does that. I mean something that … You know, people want to fit in, be like everybody else. And if there’s something inside you that makes you … You know it’s totally wrong, weird; you’ll never be like everybody else—but you still really want it. And that hurts, and it also makes you maybe more careful? About trying to fit in. Which is maybe more important when you’re my age.”

I looked at her with a little bit of surprise. I had forgotten that she was eighteen, and rumored to be bright. Perhaps whatever drugs they had given her were wearing off, and maybe she was just glad to have somebody to talk to for the first time in quite a while. Whatever the case, she was finally showing a little bit of depth, which at least removed one small layer of torture from durance vile.

“It’s not,” I said. “It stays important your whole life.”

“But it feels so much more hurtful,” she said. “When you’re young, and it’s like there’s a party going on all around you, but you weren’t invited.” She looked away, not at the blood, but at the bare steel wall.

“All right,” I said. “I do know what you mean.” She looked at me encouragingly. “When I was your age, I was different, too. I had to work very hard to pretend to be like everyone else.”

“You’re just saying that,” she said.

“No,” I said. “It’s true. I had to learn to act like the cool kids, and how to pretend I was tough, and even how to laugh.”

“What,” she said with another of her two-syllable chuckles. “You don’t know how to laugh?”

“I do now,” I said.

“Let’s see.”

I made one of my perfect happy faces, and gave her a very realistic that’s-a-good-one chuckle.

“Hey, pretty good,” she said.

“Years of practice,” I said modestly. “It sounded pretty horrible at first.”

“Uh-huh, well,” she said, “I’m still practicing. And for me it’s a whole lot harder than just learning to laugh.”

“That’s just teenaged self-involvement,” I told her. “You think everything is harder for you, because it’s you. But the fact is, being a human being is very hard work and it always has been. Especially if you feel like you’re not one.”

“I think I am,” she said softly. “Just a really, really different kind.”

“Okay,” I said, and I admit that I was starting to feel a little bit intrigued. Who knew she would turn out to be such a person? “But that’s not a bad thing. And if you can just give it some time, it might actually turn out to be a good thing.”

“Yeah, right,” she said.

“And you can’t do that if you don’t get out of here—staying here is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.”

“That’s cute,” she said.

She was back to being flippant again, which frayed at my new human temper. She had begun to seem interesting, and I had opened up, started to like her, even felt real, actual empathy for her—and now she was slipping back into her aloof, teenage, you-can’t-know disguise, and it made me just a little bit cranky and filled me with the urge to shake her up. “For God’s sake,” I said. “Don’t you understand why you’re in here? These people are going to cook you and eat you!”

She looked away again. “Yeah, I know,” she said. “That’s what I want.” She looked back at me, her eyes large and moist. “That’s my big secret,” she said.

ePub

ePub A4

A4