Chapter 16

'A

rkady? Yeah, he's got a smallholding about six miles from here. Keeps pigs, I think. He's a decent enough bloke. Never been in any kind of trouble. He beat the crap out of Rado after his arrest, so I heard.''Does he have other kids, this Arkady Matic?'

'There's a grown-up daughter, I think. But she's not living at home.'

'Where exactly is this farm?'

'You want the address or directions?'

'Both, please, if you don't mind.' The Shark could hear the obsequiousness in his voice, but he didn't care if he was crawling. He just wanted the information.

Schumann gave him a detailed description of how to find the Matic family farm. 'What do you want with them anyway?' he asked.

'I don't really know. I'm making inquiries on behalf of one of the other detectives here,' The Shark said apologetically. 'You know how it is. You clear your own case and somebody thinks you've got time on your hands...'

'Tell me about it,' Schumann complained. 'Do me a favour, though. If your colleague is thinking about coming on to my patch, get him to call me first.'

'He's a she,' The Shark said. 'I'll pass the message on. Thanks for your help.' Bollocks to that, he thought. He wasn't going to ask Detective Schumann's permission to check out Matic's farm. He wasn't sharing his moment of glory with some provincial plod.

He jumped to his feet and practically ran out of the squad room, grabbing his jacket on the way. He had a good feeling about this. A smallholding in the middle of nowhere was the perfect place to stash Marlene Krebs' daughter. He was on to something here. He'd show Petra he was worthy of her respect.

The hire car was waiting for Tony at Frankfurt, just as Petra had promised. He was grateful that she'd found the time to organize his trip; it would have been so much harder if he'd had to make his own arrangements. On the passenger seat was an internet-generated route plan to get him from the airport to Schloss Hochenstein in time for the appointment she'd arranged with the curator of the castle's grisly records. He didn't imagine he was going to find the ultimate answer to his quest this morning, but at least he might be able to leave with a list of names that could be used as a cross-reference if Marijke and her German colleagues managed to come up with possible candidates from the shipping community.

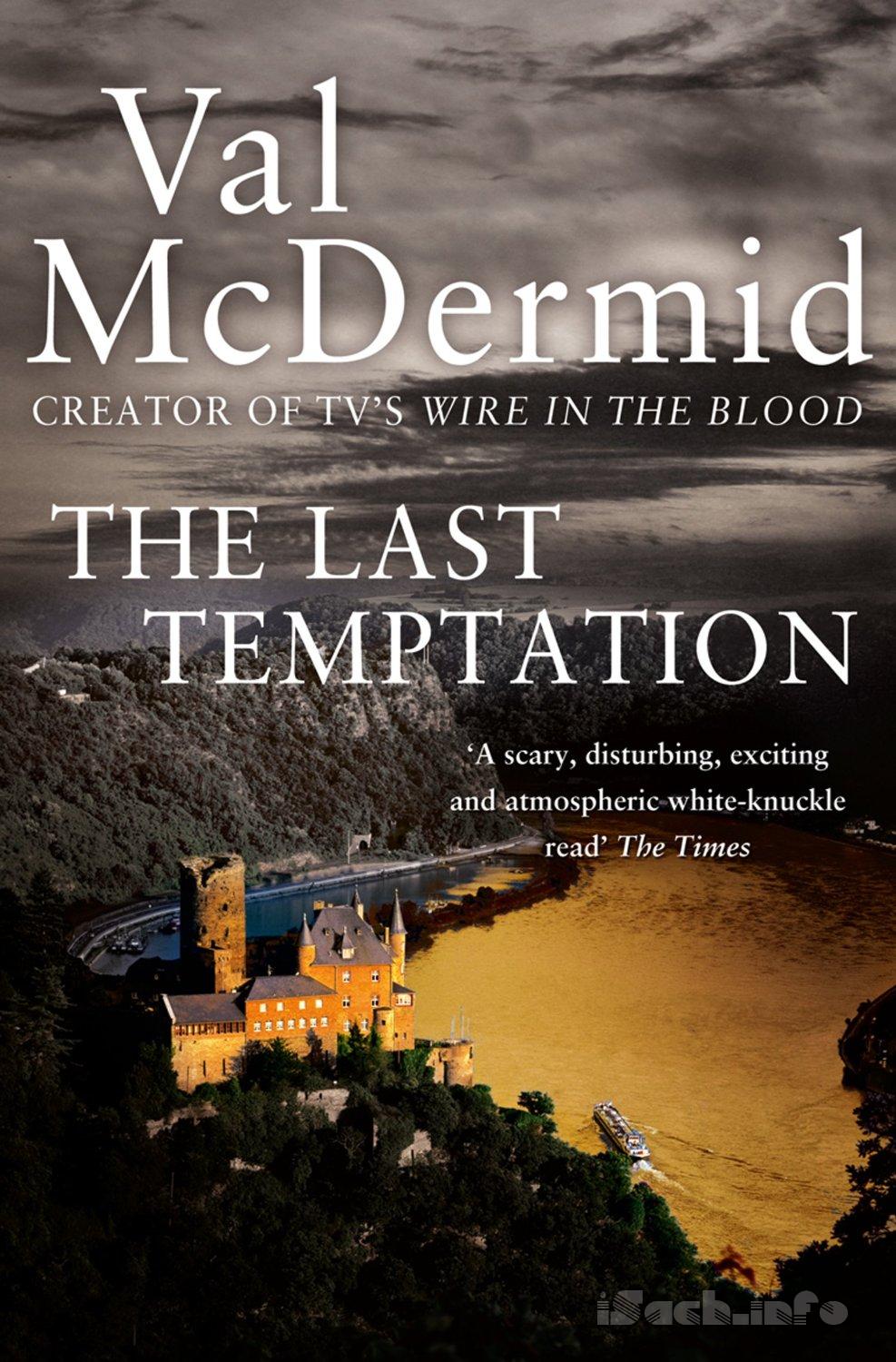

- Even on a sunny spring morning, Schloss Hochenstein was a grim sight. The winding road that led up from the valley floor to the castle sitting on its bluff offered occasional glimpses of its forbidding grey walls and turrets. This was no fairytale Rhineland castle, he realized, as he rounded the final bend and came face to face with the looming edifice. There was nothing graceful about the schloss. It hunkered on top of the tor like a fat toad, everything about it heavy and overbearing. The towers on each corner were squat and ugly, the crenellated battlements threatening. This was a place to strike fear Into the heart of your enemies, Tony thought, gazing up at the facade.

He parked in the visitor car park to one side of the castle and walked across the lowered drawbridge. Instead of a water filled moat, there was a deep stone-lined ditch with savage iron spikes festooning the sides and bottom. Above the gateway were elaborate stone carvings of mythical beasts engaged in combat. A griffin crouched on the back of a unicorn, its claws buried in the unicorn's neck. A strange serpent had its fangs plunged into the throat of a wyvern. As symbolic greetings went, Tony thought they might as well have carved, 'Abandon hope all ye who enter here,' and have done.

In the gatehouse, there was a ticket office. Tony walked up to it and told the attendant he had an appointment with Dr Marie Wertheimer. The man nodded gloomily and picked up the phone. 'She will be with you now,' he said, indicating to Tony that he should proceed into the courtyard of the keep. High walls towered over him, their narrow windows suggesting an army of hostile eyes. He imagined how this must have appeared to the frightened children herded here and shivered in spite of himself.

A rotund figure approached across the courtyard, swathed in a maroon woollen wrap. The woman looked like an autumn berry on legs, her greying hair twisted on top of her head in a neat bun. 'Dr Hill? I'm Marie Wertheimer, curator of the records here at Schloss Hochenstein. Welcome.' Her English was almost without accent.

'Thank you for making the time to see me,' Tony said, shaking her tiny plump hand.

'It's my pleasure. It's always interesting to have a break from routine. So, why don't we have a coffee and you can tell me exactly what it is that interests you.'

He followed her through a small studded wooden door at the base of the keep and down a flight of worn stone steps.

'Mind your step,' she cautioned him. 'These stairs can be treacherous. Best to keep close to the handrail.'

They turned into a low corridor, lit with glaring fluorescent strips. 'We have the least attractive quarters in the castle,' Dr Wertheimer said. 'The part the tourists never get to see.' She turned abruptly into a doorway that opened into a large room lined with utilitarian metal shelving. To his surprise, it had narrow lancet windows along one wall. 'Not a very enticing view,' she said, noting his glance. 'We look out on to the ditch. Still, at least I have some natural light, which is more than most of my colleagues. Please, take a seat, make yourself comfortable.'

Tony sat in one of a pair of battered armchairs set in a corner of the office while Dr Wertheimer fussed with kettle and coffee pot. She brought him a mug of startlingly viscous coffee and settled herself in the chair opposite him. 'I'm very curious,' she said. 'When I spoke to your colleague from Berlin, she was reluctant to give me any details of the nature of your inquiries.'

Tony sipped cautiously. There was enough caffeine in the brew to keep a narcolept awake for days. 'It's a very sensitive matter,' he said.

'We're accustomed to sensitive matters here,' Dr Wertheimer said tartly. 'Our archive contains material that is still extremely uncomfortable for my fellow countrymen to contemplate. So, I need to be clear about the purpose of your visit. You can speak confidentially to me, Dr Hill. It won't go any further.'

He sized up the placid face with its sharp eyes. He was inclined to trust this woman, and he suspected that, unless he opened up to her, she would be reluctant to do the same for him. 'I'm an offender profiler,' he said. 'I was brought in to help with an investigation into a series of murders that we believe have been committed by the same person.'

Dr Wertheimer frowned. 'The university lecturers?' she said sharply. Astonished, Tony simply gaped at her. 'You have not seen the newspapers this morning?' She got up and rummaged in a large shopping bag at the side of her desk. She produced a copy of that morning's Die Welt and turned to an inside page. 'You read German?' she asked.

He nodded, still not trusting speech. She handed him the newspaper and settled down in her chair while he read it. The headline was straightforward. Three murders - Are they linked? The text went on to point out that within the past two months, three university psychology lecturers had been found dead in suspicious circumstances. In each case, the police had been reluctant to divulge details of the deaths, except to say that each was being treated as murder. The writer went on to speculate as to whether this might be the work of a serial killer, although he had been unable to find a police source who would confirm the theory.

'I imagine that there will be other stories in the press,' Dr Wertheimer said as he finished. 'I doubt they will be so restrained. So, is this what brings you to our records here?'

Tony nodded. 'I'm sorry I wasn't more candid with you, but we have been trying to keep this out of the public arena.'

'I can imagine. No police officer is comfortable working in the glare of the TV lights. So, what is it you hope to accomplish here?'

'We need to narrow down our field of suspects. Dull, boring police work involving cross-referencing various lists. It's tedious and time-consuming for the officers involved, but it could produce a result that will save lives. My analysis of the crimes leads me to think that it's likely someone in our killer's immediate family was the victim of psychological torture. I was told that you hold the archives relating to chil dren who were either euthanased or experimented on by Nazi doctors. I'm hoping that somewhere in your archives there is a list of survivors.'

Dr Wertheimer raised her eyebrows. 'This was a long time ago, Dr Hill.'

'I know. But I believe our killer is probably in his mid twenties. It's possible that his father may have been a survivor. Or he may have been brought up by a grandparent who suffered at the hands of the people who operated institutions such as this.'

She nodded acquiescence. 'It seems far-fetched to me, but I can see that you would want to clutch at any straw when you are trying to bring such a killer to justice. Well, we have no master list such as you speak of.'

Tony couldn't help showing his disappointment on his face. 'So I'm wasting your time as well as my own?'

She shook her head. 'No, of course not. What we do have is individual lists for each of the institutions involved in this programme. There were six main centres where the euthanasia was carried out, but for each of those there were several feeder institutions. We hold records for all of these.' She saw his look of dismay and smiled. 'Please don't despair. The good news is that all our data has been computerized, and so it is relatively easy to access. Normally, I would insist that you carried out ^any ^tudy here on the premises, but I can see that these are special circumstances. Perhaps you would like to contact Ms Becker and ask her to fax me a warrant that would allow me to provide you with hard copies of our data under a confidentiality agreement?'

Tony couldn't believe his luck. For once, he'd found a bureaucrat who didn't want to put obstacles in his way. 'That would be extraordinarily helpful,' he said. 'Is there a phone I can use?'

Dr Wertheimer pointed to her desk. 'Be my guest.' He followed her across the room and waited while she scribbled down the fax number. 'I expect it will take a little time for her to obtain the necessary warrant, but we may as well make a start. I'll go and ask one of my colleagues to print out the appropriate data. I'll be back shortly.'

She bustled out of the room, leaving Tony to call Petra. When she answered her mobile, he explained what he needed. 'Shit, that's not going to be easy,' she muttered.

'What's the problem?'

'I'm not supposed to be working on this, remember? I can hardly make a formal request for a warrant for a case that's nothing to do with me. Have you seen the papers?'

'I've seen Die Welt:

'Believe me, that's the least of our worries. But now that everybody knows there's a serial killer out there, of course, they also know it's really nothing to do with me.'

'Ah,' Tony said. He'd wondered when the woman who got things done would finally hit a brick wall. It was just a pity that it had happened now.

'Let me think...'Petra said slowly. "There's a guy in KriPo who really wants to work in intelligence. I know he's got the right people in his pocket. Maybe I could persuade him that it would help him get a move on to my team if he pulled some strings for me on this.'

'Is there anything that's beyond you, Petra?'

'This might be. Depends how sensitive this guy's bullshit detector is. Keep your fingers crossed for me. Oh, and something very interesting came up in the Koln investigation. Marijke just e-mailed me about it. They found a colleague of Dr Calvet's who remembered her saying something about a meeting with a journalist from a new e-zine, though she couldn't swear to when they were supposed to get together.'

'That confirms what Margarethe told her partner.'

'More than that, Tony. It tells us we're on the right track.'

He could hear a note of excitement in her voice. 'What do you mean?'

'The colleague remembered the alias the journalist was using.' She paused expectantly.

'And?'

'Hochenstein.'

'You're kidding.' He knew she wasn't.

'The colleague remembered it because it isn't exactly a common name and, of course, Hochenstein has particular resonances for experimental psychologists in Germany.'

'I bet it does. Well, at least that tells us I'm fishing in the right river.'

'Happy hunting. I'll talk to you later.'

He replaced the phone and walked over to the window. Dr Wertheimer had been right. This wasn't a view for anyone who had depressive tendencies, he thought. He imagined the children cooped up behind these high walls, their lives narrowed to the prospect of death or torture. He supposed some of them were too profoundly handicapped to have been conscious either of their surroundings or their imminent fates. But for the others, those incarcerated because of their supposed anti-social behaviour or minor physical defects, the anguish must have been unbearable. To be wrested from their families and dumped here would have traumatized the best adjusted of children. For those already damaged, it must have been disastrous.

His reverie was broken by the return of Dr Wertheimer. 'The material you need is being printed out,' she said. 'We have lists of names and addresses, and in many cases there are also brief digests of some of the so-called treatments they endured.'

'It's amazing that the records survived,' Tony said.

She shrugged. 'Not really. They never thought for a moment they would ever be called to account. The idea that the Third Reich might collapse so spectacularly and thoroughly was unimaginable for those who were part of the establishment. By the time the truth dawned on them, it was too late to think of anything else except immediate personal survival. And it soon became clear that there were far too many guilty men and women for any but the most senior to face retribution. We began archiving records in the early 19805 and, after reunification, we were able to track down most of the old ones from the East too. I'm glad we have them. We should never forget what was once done in the name of the German Volk.'

'And what exactly was done to these children?' he asked.

Dr Wertheimer's eyes lost their sparkle. 'The ones who survived? They were treated like lab rats. Mostly they were kept down here, in a series of cells and dormitories. The staff called it the U-Boot - the submarine. No natural light, no sense of night and day. They did various experiments with sleep deprivation, altering the length of the perceived days and nights. They would allow a child to sleep for three hours, then wake it and say, "It's morning, here's your breakfast." Two hours later, they would serve lunch. Two hours later, dinner. Then they would be told it was night and the lights would be turned off. Or else the days would be stretched out.'

'This was supposed to be research, right?' Tony asked, the tang of disgust in his throat. It never failed to appal him that members of his own profession could move so far from the avowed duty to help those entrusted to their care. There was something frighteningly personal about this case, summoning as it did the images of a nightmare that had been created by men and women who must at some point have believed in the therapeutic possibilities of their work. That they could have been so readily corrupted from that ideal was frightening because it was a stark reminder of how thin the veneer of civilization truly was.

'This was indeed supposed to be research,' Dr Wertheimer agreed sadly. 'It was supposed to help the generals decide how hard troops could be driven. Of course, it had no practical application whatsoever. It was simply the exercise of power over the weak. Doctors indulged their own whims, tested their own notions to destruction. We had a water torture cell here where they performed acts of unspeakable cruelty both physical and mental.'

'Water torture?' Tony's interest was pricked.

'We weren't the only institution to have such a facility. Notoriously there was also one at the Hohenschonhausen prison in Berlin, but that was for adults. Here, the subjects were children and the intent was supposedly experiment rather than punishment or interrogation.'

'Did they force water down the children's throats at all?' Tony asked.

Dr Wertheimer frowned at the floor. 'Yes. They conducted several series of experiments to test physical resistance to this. Of course, many of the children died. It takes a surprisingly small amount of water to drown a child if you force water into their airway.' She shook her head, as if willing the images away. 'They also used it in psychological experiments. I don't have the details of those, but they will be in the records somewhere.'

'Would you be able to find them for me?'

'Probably not today, but I can have someone make a search.' Before Tony could respond, the fax phone rang. Dr Wertheimer crossed the room and watched as the paper spewed out. 'It looks as if your colleague has been successful,' she said. 'It'll take a while for everything to be printed out. Would you like to take a tour of the castle while you wait?'

He shook his head. 'I don't feel much like a tourist experience right now.'

Dr Wertheimer nodded. 'I quite understand. We have a cafeteria in the main courtyard. Perhaps you would like to wait there, and I'll bring the material to you?'

Three hours later, he was back on the road, a thick bundle of papers in a padded envelope next to him. He wasn't looking forward to reading the contents. But, with luck, it might take them a small step closer to a killer. ?

The wind tumbled Carol's hair and dredged the stale city air from the depths of her lungs. She could imagine how easily Caroline Jackson might have succumbed to the delights of being whisked off into the spring sunshine in a BMW ragtop roadster. What woman wouldn't? But although part of her was enjoying the sensation of racing down an autobahn at a speed far in excess of anything she could legitimately have experienced in the UK, there was nothing unalloyed about her reactions. Carol was subsumed in Caroline, but she knew who was firmly in control.

Tadeusz had called for her at half past ten, having phoned to instruct her to dress warmly but casually while teasingly refusing to tell her why. When she'd emerged on the street to find him at the wheel of a black Z8 with the top down, he'd taken one look at the thin jacket covering her sweater and pursed his lips. 'I was afraid of this,' he said, going round to the boot. He produced a heavy sheepskin bomber jacket and handed it to her. 'This should fit you, I think.'

Carol took the coat gingerly. It wasn't new. There were creases at the elbow that proved that. She took off her own jacket and slipped her arms into the sleeves of the sheepskin.

He was right. It fit as snugly as anything in her own wardrobe. She detected the faint musk of a heavy perfume she would never have worn. She looked up at Tadeusz with a wry smile. 'Was this Katerina's?' she asked. ?

'You don't mind?' he said anxiously.

'As long as you don't.' Carol hid her unease with a smile. There was something unnervingly creepy about wearing Katerina's clothes. It felt as if somewhere in Radecki's head, the boundaries were starting to blur. And that almost certainly spelled danger for her in one way or another.

He shook his head and opened the passenger door for her. 'I cleared out most of her clothes, but I kept one or two things that I loved to see her in. I didn't want you to be cold today, and it seemed somehow less presumptuous than going out and buying something for you.'

She stood on tiptoe and kissed his cheek. 'That was very thoughtful. But, Tadzio, you don't have to take responsibility for me. I'm a grown-up with my own platinum card. You don't have to second-guess my needs. I'm used to meeting them myself.'

He took the gentle rebuke well. 'I never doubted it,' he said, handing her into the car. 'But sometimes, Caroline, you have to give in to being pampered a little.' He winked and walked round to the driver's seat.

7> 'Where are we off to, then?' she asked as they turned left down the Ku'damm towards the ring road.

'You said you wanted to see how things work in my business,' Tadeusz said. 'Yesterday, you saw the legitimate side. Today, I'm going to show you how we move our commodities. We're going towards Magdeburg.'

'What's at Magdeburg?'

'You'll see.'

Eventually Tadeusz pulled off the autobahn and, without pausing to consult a map, he took several turns that finally brought them to a quiet country road meandering among farms. After ten minutes or so, the road ended on the banks of a river. He turned off the engine and said, 'Here we are.'

'Where is here?'

'The banks of the River Elbe.' He gestured to his left. 'Just up there is the junction with the Mittelland Kanal.' He opened the door and climbed out. 'Let's walk.'

She followed him along a path by the river, which was busy with commercial craft ranging in size from long barges loaded down with containers to small boats carrying a few crates or sacks. 'It's a busy waterway,' she commented, falling into step beside him.

'Precisely. You know, when people think of moving illegal goods around, whether that's arms or drugs or human beings, they always think of the fastest ways of doing it. Planes, lorries, cars. But there's no reason for speed. You're not carrying perishable cargo. And smuggling really started on the water,' Tadeusz said. As the canal came into view, he reached out and took her hand in his.

'This is one of the crossroads of the European waterways,' he said. 'From here, you can go to Berlin or Hamburg. But you can go much, much further. You can use the Havel and the Oder to take you to the Baltic or into the heart of Poland and the Czech Republic. In the other direction, there's Rotterdam, Antwerp, Ostende, Paris, Le Havre. Or you can go down the Rhine and the Danube all the way to the Black Sea. And nobody really takes much notice. As long as you have the proper seals on your containers and the appropriate documents, there's nothing to worry about.'

'This is how you move your merchandise?' Carol said, sounding bemused.

He nodded. 'The Romanians are extremely corruptible.

The drugs come across the Black Sea, or else from the Chinese as payment for their travel. The guns come from the Crimea. The illegals come into Budapest or Bucharest on tourist visas. And they all get packed into containers with official customs seals and end up where I want them to be.'

'You pack people into containers? For weeks at a time?'

He smiled. 'It's not so bad. We have containers with special air filters. Chemical toilets. Plenty of water and enough food so they don't starve. Frankly, they don't care how bad the conditions are as long as they end up in some nice EU country with a welfare system and a lousy procedure for getting rid of asylum seekers. One of the reasons they love your country so much,' he added, giving her fingers a gentle squeeze.

'So you load them all up in the docks on the Black Sea? And everybody turns a blind eye?' Even with corruptible officials, Carol thought this was a rather chancy operation.

He laughed. 'Hardly. No, when the containers leave Agigea, they're full of perfectly legitimate merchandise. But I own a small boatyard about fifty kilometres from Bucharest. Near Giurgiu. The barges pull in there and the loads are ... how can I put it? Rectified. The legitimate cargoes are transferred to lorries. And our tame customs officials replace the seals so everything is exactly as it should be.' He dropped her hand and put an arm round her shoulders. 'You see how much I trust you, that I tell you all this?'

'I appreciate it,' Carol said, trying not to show how overjoyed she was at the precious intelligence she had gained. 'So how many containers do you have in operation at any given time?' she asked. It was, she felt, the sort of thing a businesswoman like Caroline would want to know.

'Between thirty and forty,' he said. 'Sometimes there's only a small amount of heroin on board, but it still means you need access to a whole container.'

'That's a big investment,' Carol said.

'Believe me, Caroline, every container pays for itself many times over every year. This is a very lucrative business. Maybe if things work out for us with the illegals, we could move some other merchandise?'

'I don't think so,' she said firmly. 'I don't get involved in drugs. It's too dodgy. Too many stupid people thinking it's easy money. You have to deal with such shitty, unreliable toerags. People you wouldn't want in your town, never mind in your house. Besides, the police pay far too much attention to drugs.'

He shrugged. 'It's up to you. Me, I let Darko deal with the scum. I only talk to the people at the top of the tree. What about guns? How do you feel about them?'

'I don't use them and I don't like them.'

Tadeusz laughed in pure delight. 'I feel the same about drugs. But it's just business, Caroline. You can't afford to be sentimental in business.'

'I'm not sentimental. I've got a very good and very profitable business and I don't want to have to deal with gangsters.'

'Everybody needs a second profit centre.'

'That's why I bought the airbase. That's why I'm here now. You supply the workforce, that's all I need.'

He pulled her closer to him. 'You shall have them.' He turned and kissed her lips. 'Sealed with a kiss.'

Carol allowed herself to lean into him, aware she mustn't reveal the repugnance his revelations had engendered in her. 'We'll make good partners,' she said softly.

'I'm looking forward to it,' he said, his voice heavy with secondary meaning.

She chuckled as she pulled free of his embrace. The too. But remember, I don't mix business with pleasure. First, we do the business. Then... who knows?' She skipped away from him and ran back down the path towards the car.

He caught up with her halfway along the river bank, grabbing her round the waist and pulling her close. COK, business before pleasure,' he said. 'Let's go back to Berlin and make some plans. I'll call Darko and get him to meet us. We've got a quiet little office in Kreuzberg where we can sit down and make some firm plans and talk money. Then tonight we can relax.'

Oh shit, Carol thought. This was all moving faster than she really wanted. How was she going to get out of this in one piece?

Petra looked up gratefully from her computer as The Shark barged into the squad room. Her head was a slow throb of red-eyed pain from too many hours staring at the screen. Her only break had been arranging the warrant for Tony. Late night reading of the murder files followed by a morning of assimilating Carol's reports and cross-referencing them with the existing files on Radecki had left her convinced she could no longer avoid a visit to the optician. This was it, then. The end of youth. First it would be reading glasses, then contact lenses, then she'd probably need a hip replacement. It all felt too grim to think about, so even The Shark was a welcome distraction.

'Got any codeine?' she demanded before he could open his mouth.

'I've got better than codeine,' he said. 'I know where Marlene's kid is.' He stood there grinning, an overgrown child who knew he'd done the one thing that his mother would approve of.

Petra couldn't stop her mouth falling open. 'You're kidding,' she said.

The Shark was literally bouncing on the balls of his feet. 'No way, Petra. I'm telling you, I've found Tanja.'

'Jesus, Shark, that's amazing.'

'It was your idea,' he said, his words tumbling over each other. 'You remember? You set me looking for Krasic's contacts? Well, I eventually found this cousin, he's got a pig farm on the outskirts of Oranienburg, his son Rado is one of Krasic's gophers, apparently. So I went over there to check it out. Lo and behold, they've got the girl!'

'You didn't go near the house, did you?' Petra felt a moment's panic. He wasn't that much of a liability, was he?

'No, of course I didn't. I was going to go out there last night, then I thought it'd make more sense to wait till morning. Daylight, you know? Anyway, I got up before dawn, put on my oldest clothes and went across the fields. I found a place where I could see the back of the house and I crawled under a hedge and staked it out. God, it was horrible. Cold and muddy, and I had no idea how much pigs fart. The bastards seemed to know I was there, kept walking right up to me and farting in my face.'

'Never mind the fucking pigs, Shark. What did you see?'

'Well, it's a lovely day, right? Perfect spring weather? Anyway, around seven, this middle-aged guy built like a brick shithouse comes out on a little quad bike and feeds the pigs. Nothing much happens for a while, then the back door opens and a woman comes out. Looks like she's in her late forties. She walks around the yard, taking a good look around her. There's a lane runs along the side of the yard and she sticks her head over the fence, like she's checking if it's all clear. Then she goes back in the house and comes out with this little girl. I had my binoculars with me, and I could see straight off it was Marlene's kid. I couldn't believe my luck. Anyway, the woman is holding Tanja by the hand, then she lets her go, and I can see she's got a rope tied round the little girl's waist. The kid tries to run off, but she gets yanked off her feet before she's gone a dozen yards. The woman walks her round the yard for ten minutes like a dog on a lead, then picks her up and carries her back indoors.'

'You're sure this was Tanja?'

The Shark nodded like a man with palsy. Tm telling you, Petra, no mistaking her. I had her photo with me, just to be on the safe side. It was Tanja. No messing.' He gave her an eager grin.

Petra shook her head, hardly able to believe that the bone she'd thrown to keep him quiet had given them so much to chew on. Much as she had come to respect Carol Jordan and the quality of the work she was doing, she still wanted to nail Radecki herself. And it looked as if she might finally have her hand on the lever that would deliver him to her. 'That's terrific, Sharkster.'

'So what do we do now?' he demanded.

'We go and see Plesch and decide how we're going to liberate the kid and take care of Marlene so Krasic and Radecki can't reach out for her. Well done, kid. I'm impressed.'

It was all he wanted to hear. A grin split his face from ear to ear. 'It was your idea, Petra.'

'Maybe. But it was your hard work that made it happen. Come on, Shark. Let's make Plesch's day.'

When Tadeusz had told her his was a small office, he hadn't been joking, Carol thought. There was barely enough room for the table and four chairs in the room above the amusement arcade. However, in spite of the scruffy stairway that led upstairs, the office itself was as plush as she would have expected. It reeked of stale cigar smoke, but the furnishings were expensive leather executive desk chairs and the table was a solid piece of limed oak. A bottle of marc de champagne and one of Jack Daniels sat on a small side table beside four crystal tumblers, and the ashtrays were four pieces of hand-crafted glass. The walls and ceiling were lined with sound-absorbing tiles so that none of the electronic cacophony from below penetrated this quiet sanctum.

'Very choice,' Carol said, spinning one of the chairs on its swivel. 'I see you like to impress those you do business with.'

Tadeusz shrugged. 'Why be uncomfortable?' He glanced at his watch. 'Make yourself at home. Darko will be here any time now. Would you like a drink?'

She shook her head. 'A bit early in the day for me to hit the brandy.' She settled down in the chair facing the door.

Tadeusz raised his eyebrows. 'The bodyguard's seat, huh?'

'What?'

'Bodyguards always sit where they can see the door.'

Carol laughed. 'And women over thirty always sit with their backs to the window, Tadzio.'

'Not something you have to worry about, Caroline.'

Before she could respond to the compliment, the door opened. Fuck me, it's a Centurion tank with legs, Carol thought.

Krasic stood on the threshold, shoulders almost as broad as the doorway itself. His eyes were shadowed under frowning brows as he took in the scene. Turn on the charm, Carol, she told herself, jumping to her feet. She crossed the short distance between them, hand extended, smile masking the deep unease this man's physical presence provoked in her. 'You must be Darko,' she said cheerfully. 'It's a pleasure to meet you.'

He took her hand in a surprisingly gentle grip. 'Mine is pleasure,' he said in heavily accented English, his brooding stare giving the lie to his words. He looked over her shoulder and said something in rapid German.

Tadeusz snorted with laughter. 'He says you're every bit as beautiful as I said. Darko, you are such a smooth-talking bastard with the ladies. Come on, sit down, have a drink.'

Krasic pulled out a chair for Carol, poured himself a Jack Daniels and sat down opposite her, his eyes fixed on her face.

ePub

ePub A4

A4