Chapter Chapter Eleven

'I

'll hustle,' Vic promised solemnly, and she passed on her way back up to the galley, resplendent in her powder-blue slacks uniform and her smile.'What's with you?' Roger asked.

'What do you mean, what's with me?'

'You know what I mean. I never even saw you drink a beer before noon before. Usually not before five.'

'I'm launching the boat,' Vic said.

'What boat?'

'The R.M.S. Titanic,' Vic said.

Roger frowned. 'That's sort of poor taste, don't you think?'

He did, as a matter of fact. Roger deserved something better, but this morning, with the depression still on him like a foul-smelling blanket, he just couldn't think of anything better. He managed a rather bleak smile instead. But Roger went on frowning at him.

'Look,' Vic said, 'I've got an idea on this Zingers thing. It's going to he a bitch convincing old man Sharp and the kid, but it might work.'

Roger looked relieved. It was the way it had always worked with them; Vic was the raw idea man, Roger the shaper and implementer. They had always worked as a team when it came to translating the ideas into media, and in the matter of presentation.

'What is it?'

'Give me a little while,' Vic said. 'Until tonight, maybe. Then we'll run it up the flagpole -'

��-and see who drops their pants,' Roger finished with a grin. He shook his paper open to the financial page again. 'Okay. As long as I get it by tonight. Sharp stock went up another eighth last week. Were you aware of that?'

'Dandy,' Vic murmured, and looked out the window again. No fog now; the day was as clear as a bell. The beaches at Kennebunk and Ogunquit and York formed a panoramic picture postcard - cobalt blue sea, khaki sand, and then the Maine landscape of low hills, open fields, and thick bands of fir stretching west and out of sight. Beautiful. And it made his depression even worse.

If I have to cry, I'm damn well going into the crapper to do it, he thought grimly. Six sentences on a sheet of cheap paper had done this to him. It was a goddam fragile world, as fragile as one of those Easter eggs that were all pretty colors on the outside but hollow on the inside. Only last week he had been thinking of just taking Tad and moving out. Now he wondered if Tad and Donna would still be there when he and Roger got back. Was it possible that Donna might just take the kid and decamp, maybe to her mother's place in the Poconos?

Sure it was possible. She might decide that ten days apart wasn't enough, not for him, not for her. Maybe a six months' separation would be better. And she had Tad now. Possession was nine points of the law, wasn't it?

And maybe, a crawling, insinuating voice inside spoke up, maybe she knows where Kemp is. Maybe she'll decide to go to him. Try it with him for a while. They can search for their happy pasts together Now there's a nice crazy Monday morning thought, he told himself uneasily.

But the thought wouldn't go away. Almost, but not quite.

He managed to finish every drop of his screwdriver before the plane touched down at Logan. It gave him acid indigestion that he knew would last all morning long - like the thought of Donna and Steve Kemp together, it would come creeping back even if he gobbled a whole roll of Turns - but the depression lifted a little and so maybe it was worth it.

Maybe.

Joe Camber looked at the patch of garage floor below his big vise damp with something like wonder. He pushed his green felt hat back on his forehead, stared at what was there awhile longer, then put his fingers between his teeth and whistled piercingly.

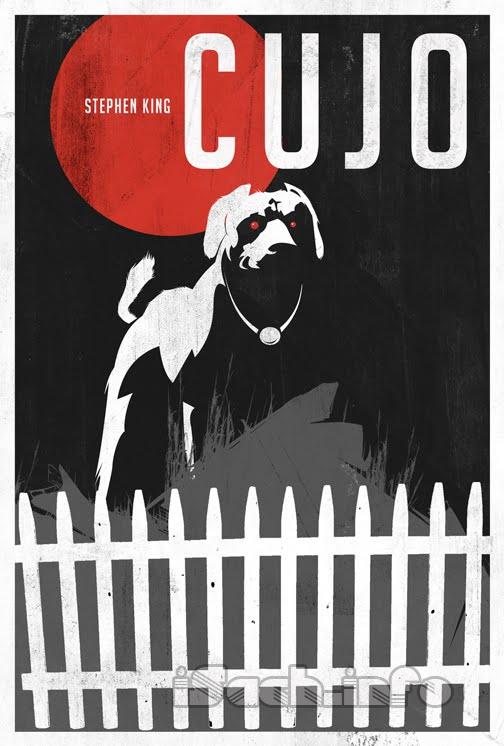

'Cujo! Hey, boy! Come, Cujo!'

He whistled again and then leaned over, hands on his knees. The dog would come, he had no doubt of that. Cujo never went far. But how was he going to handle this?

The dog had shat on the garage floor. He had never known Cujo to do such a thing, not even as a pup. He had piddled around a few times, as puppies will, and he had tom the bejesus out of a chair cushion or two, but there had never been anything like this. He wondered briefly if maybe some other dog had done it, and then dismissed the thought. Cujo was the biggest dog in Castle Rock, so far as he knew. Big dogs ate big, and big dogs crapped big. No poodle or beagle or Heinz Fifty-seven Varieties had done this mess. Joe wondered if the dog could have sensed that Charity and Brett were going away for a sped. If so, maybe this was his way of showing just how that idea set with him. Joe had heard of such things.

He had taken the dog in payment for a job he had done in 1975. The customer had been a one-eyed fellow named Ray Crowell from up Fryeburg way. This Crowell spent most of his time working in the woods, although it was acknowledged that he had a fine touch with dogs - he was good at breeding them and good at training them. He could have made a decent living doing what New England country people sometimes called 'dog farming', but his temper was not good, and he drove many customers away with his sullenness.

'I need a new engine in my truck,' Crowell had told Joe that spring.

'Ayuh,' Joe had said.

'I got the motor, but I can't pay you nothing. I'm tapped out.'

They had been standing just inside Joe's garage, chewing on stems of grass. Brett, then five, had been goofing around the dooryard while Charity hung out clothes.

'Well, that's too bad, Ray,' Joe said, 'but I don't work for free. This ain't no charitable organization.'

'Mrs. Beasley just had herself a litter,' Ray said. Mrs. Beasley was a prime bitch Saint Bernard. 'Purebreds. You do the work and I'll give you the pick of the litter. What do you say? You'd be coming out ahead, but I can't cut no pulp if I don't have a truck to haul it in.'

'Don't need a dog,' joe said. 'Especially a big one like that. Goddam Saint Bernards ain't nothing but eatin machines.'

'You don't need a dog,' Ray said, casting an eye out at Brett, who was now just sitting on the grass and watching his mother, 'but your boy might appreciate one.'

Joe opened his mouth and then closed it again. He and Charity didn't use any protection but there had been no more kids since Brett, and Brett himself had been a long while coming. Sometimes, looking at him, a vague question would form itself in Joe's head: Was the boy lonely? Perhaps he was. And perhaps Ray Crowell was right. Brett's birthday was coming up. He could give him the pup then.

'I'll think about it,' he said.

'Well, don't think too long,' Ray said, bridling. 'I can go see Vin Callahan over in North Conway. He's just as handy as you are, Camber. Handier, maybe.'

'Maybe,' Joe said, unperturbed. Ray Crowell's temper did not scare him in the least.

Later that week, the manager of the Shop'n Save drove his Thunderbird up to Joe's to get the transmission looked at. It was a minor problem, but the manager, whose name was Donovan, fussed around the car like a worried mother while Joe drained the transmission fluid well, refilled it, and tightened the bands. The car was a piece of work, all right, a 1960 T-Bird in cherry condition. And as he finished the job, listening to Donovan talk about how his wife wanted him to sell the car, Joe had, had an idea.

'I'm thinking about getting my boy a dog,' he told this Donovan as he let the T-Bird down off the jacks.

Oh, yes?' Donovan asked politely.

Ayuh. Saint Bernard. It's just a pup now, but it's gonna eat big when it grows. Now I was just thinking that we might make a little deal, you and me. If you was to guarantee me a discount on that dry dog food, Gaines Meal, Ralston-Purina, whatever you sell, I'd guarantee you to work on your Bird here every once in a while. No labor charges.'

Donovan had been delighted and the two of them had shaken on it. Joe had called Ray Crowell and said he'd decided to take the pup if Crowell was still agreeable. Crowell was, and when his son's birthday rolled around that year, Joe had astounded both Brett and Charity by putting the squirming, wriggling puppy into the boy's arms.

'Thank you, Daddy, thank you, thank you!' Brett had cried, hugging his father and covering his cheeks with kisses.

'Sure,' joe said. 'But you take care of him, Brett. He's your dog, not mine. I guess if he does any piddling or cropping around, IT take him out in back of the barn and shoot him for a stranger.'

'I will, Daddy ... I promise!'

He had kept his promise, pretty much, and on the few occasions he forgot, either Charity or Joe himself had cleaned up after the dog with no comment. And Joe had discovered it was impossible to stand aloof from Cujo; as he grew (and he grew damned fast, developing into exactly the sort of eating machine Joe had foreseen), he simply took his place in the Camber family. He was one of your bona fide good dogs.

He had house-trained quickly and completely ... and now this. Joe turned around, hands stuffed in his pockets, frowning. No sign of Cuje anywhere.

He stepped outside and whistled again. Damn dog was maybe down in the creek, cooling off. Joe wouldn't blame him. It felt like eighty-five in the shade already. But the dog would come back soon, and when he did, Joe would rub his nose in that mess. He would be sorry to do it if Cujo had made it because he was missing his people, but you couldn't let a dog get away with

A new thought came. Joe slapped the flat of his hand against his forehead. Who was going to feed Cujo while he and Gary were gone?

He supposed he could fill up that old pig trough behind the barn with Gaines Meal - they had just about a long ton of the stuff stored downstairs in the cellar - but it would get soggy if it rained. And if he left it in the house or the barn, Cujo might just decide to up and crap on the floor again. Also, when it came to food, Cujo was a big cheerful glutton. He would cat half the first day, half the second day, and then walk around hungry until Joe came back.

'Shit,' he muttered.

The dog wasn't coming. Knew Joe would have found his mess and ashamed of it, probably. Cujo was a bright dog, as dogs went, and knowing (or guessing) such a thing was by no means out of his mental reach.

Joe got a shovel and cleaned up the mess. He spilled a capful of the industrial cleaner he kept handy on the spot, mopped it, and rinsed it off with a bucket of water from the faucet at the back of the garage.

That done, he got out the small spiral notebook in which he kept his work schedule and looked it over. Richie's International Harvester was taken care of - that chainfall surely did take the ouch out of pulling a motor. He had pushed the transmission job back with no trouble; the teacher had been every bit as easygoing as Joe had expected. He had another half a dozen jobs lined up, all of them minor.

He went into the house (he had never bothered to have a phone installed in his garage; they charged you dear for that extra line, he had told Charity) and began to call people and tell them he would be out of town for a few days on business. He would get to most of them before they got around to taking their problems somewhere else. And if one or two couldn't wait to get their new fanbelt or radiator hose, piss on em.

The calls made, he went back out to the barn. The last item before he was free was an oil change and a ring job. The owner had promised to come by and pick up his car by noon. Joe got to work, thinking how quiet the home place seemed with Charity and Brett gone ... and with Cujo gone. Usually the big Saint Bernard would lie in the patch of shade by the big sliding garage door, panting, watching Joe as he worked. Sometimes Joe would talk to him, and Cujo always looked as if he was listening carefully.

Been deserted, he thought semi-resentfully. Been deserted by all three. He glanced at the spot where Cujo had messed and shook his head again in a puzzled sort of disgust. The question of what he was going to do about feeding the dog recurred to him and he came up empty again. Well, later on he would give the old Pervert a call. Maybe he would be able to think of someone - some kid - who would be willing to come up and give Cujo his chow for a couple-three days.

He nodded his head and turned the radio on to WOXO in Norway, turning it up loud. He didn't really hear it unless the news or the ball scores were on, but it was company. Especially with everyone gone. He got to work. And when the phone in the house rang a dozen or so times, he never heard it.

Tad Trenton was in his room at midmorning, playing with his trucks. He had accumulated better than thirty of them in his four years on the earth, an extensive collection which ranged from the seventy-nine-cent plastic jobs that his dad sometimes bought him at the Bridgton Pharmacy where he always got Time magazine on Wednesday evenings (you had to play carefully with the seventy-nine-cent trucks because they were MADE IN TAIWAN and had a tendency to fall apart) to the flagship of his line, a great yellow Tonka bulldozer that came up to his knees when he was standing.

He had various 'men' to stick into the cabs of his trucks. Some of them were round-headed guys scrounged from his PlaySkool toys. Others were soldiers. Not a few were what he called 'Star Wars Guys'. These included Luke, Han Solo, the Imperial Creep (aka Darth Vader), a Bespin Warrior, and Tad's absolute favorite, Greedo. Greedo always got to drive the Tonka dozer.

Sometimes he played Dukes of Hazzard with his trucks, sometimes B. J. and the Bear, sometimes Cops and Moonshiners (his dad and mom had taken him to see White Lightning and White Line Fever on a double bill at. the Norway Drive-In and Tad had been very impressed), sometimes a game he had made up himself. That one was called Ten-Truck Wipe-Out.

But the game he played most often - and the one he was playing now -had no name. It consisted of digging the trucks and the 'men' out of his two playchests and lining the trucks up one by one in diagonal parallels, the men inside, as if they were all slant-parked on a street that only Tad could see. Then he would run them to the other side of the room one by one, very slowly, and line them up on that side bumper-to-bumper. Sometimes he would repeat this cycle ten or fifteen times, for an hour or more, without tiring.

Both Vic and Donna had been struck by this game. It was a little disturbing to watch Tad set up this constantly repeating, almost ritualistic pattern. They had both asked him on occasion what the attraction was, but Tad did not have the vocabulary to explain. Dukes of Hazzard, Cops and Moonshiners, and Ten-Truck Wipe-Out were simple crash-and-bash games. The no-name game was quiet, peaceful, tranquil, ordered. If his vocabulary bad been big enough, he might have told his parents it was his way of saying Om and thereby opening the doors to contemplation and reflection.

Now as he played it, he was thinking something was wrong.

His eyes went automatically - unconsciously - to the door of his closet, but the problem wasn't there. The door was firmly latched, and since the Monster Words, it never came open. No, the something wrong was something else.

He didn't know exactly what it was, and wasn't sure he even wanted to know. But, Iike Brett Camber, he was already adept at reading the currents of the parental river upon which he floated. just lately he had gotten the feeling that there were black eddies, sandbars, maybe deadfalls hidden just below the surface. There could be rapids. A waterfall. Anything.

Things weren't right between his mother and father.

It was in the way they looked at each other. The way they talked to each other. It was on their faces and behind their faces. In their thoughts.

He finished changing a slant-parked row of trucks on one side of the room to bumper-to-bumper traffic on the other side and got up and went to the window. His knees hurt a little because he had been playing the no-name game for quite a while. Down below in the back yard his mother was hanging out clothes. Half an hour earlier she had tried to call the man who could fix the Pinto, but the man wasn't home. She waited a long time for someone to say hello and then slammed the phone down, mad. And his mom hardly ever got mad at little things like that.

As he watched, she finished hanging the first two sheets.

She looked at them ... and her shoulders kind of sagged. She went to stand by the apple tree beyond the double clothesline, and Tad knew from her posture-her legs spread, her head down, her shoulders in slight motion - that she was crying. He watched her for a little while and then crept back to his trucks. There was a hollow place in the pit of his stomach. He missed his father already, missed him badly, but this was worse.

He ran the trucks slowly back across the room, one by one, returning them to their slant-parked row. He paused once when the screen door slammed. He thought she would call to him, but she didn't. There was the sound of her steps crossing the kitchen, then the creak of her special chair in the living room as she sat down. But the TV didn't go on. He thought of her just sitting down there, just. . . sitting ... and dismissed the thought, quickly from his mind.

He finished the row of trucks. There was Greedo, his best, sitting in the cab of the dozer, looking blankly out of his round black eyes at the door of Tad's closet. His eyes were wide, as if he had seen something there, something so scary it had shocked his eyes wide, something really gooshy, something horrible, something that was coming

Tad glanced nervously at the closet door. It was firmly latched.

Still he was tired of the game. He put the trucks back in his playchest, clanking them loudly on purpose so she would know he was getting ready to come down and watch Gunsmoke on Channel 8. He started for the door and then paused, looking at the Monster Words, fascinated.

Monsters, stay out of this room! You have no business here.

He knew them by heart. He liked to look at them, read them by rote, look at his daddy's printing.

Nothing will touch Tad, or hurt Tad, all this night.

You have no business here.

On a sudden, powerful impulse, he pulled out the pushpin that held the paper to the wall. He took the Monster Words carefully - almost reverently - down. He folded the sheet of paper up and put it carefully into the back pocket of his jeans. Then, feeling better than he had all day, he ran down the stairs to watch Marshal Dillon and Festus.

That last fellow had come and picked up his car at ten minutes of twelve. He had paid cash, which Joe had tucked away into his old greasy wallet, reminding himself to go down to the Norway Savings and pick up another five hundred before he and Gary took off.

Thinking of taking off made him remember Cujo, and the problem of who was going to feed him. He got into his Ford wagon and drove down to Gary Pervier's at the foot of the hill. He parked in Gary's driveway. He started up the porch steps, and the hail that had been rising in his throat died there. He went back down and bent over the steps.

There was blood there.

Joe touched it with his fingers. It was tacky but not completely dry. He stood up again, a little worried but not yet unduly so. Gary might have been drunk and stumbled with a glass in his hand. He wasn't really worried until he saw the way the rusty bottom panel of the screen door was crashed in.

'Gary?'

There was no answer. He found himself wondering if someone with a grudge had maybe come hunting ole Gary. Or maybe some tourist had come asking directions and Gary had picked the wrong day to tell someone he could take a flying fuck at the moon. .

He climbed the steps. There were more splatters of blood on the boards of the porch.

'Gary?' he called again, and suddenly wished for the weight of his shotgun cradled over his right arm. But if someone had punched Gary out, bloodied his nose, or maybe popped out a few of the old Pervert's remaining teeth, that person was gone now, because the only car in the yard other than Joe's rusty Ford LTD wagon was Gary's white '66 Chrysler hardtop. And You just didn't walk out to Town Road No. 3. Gary Pervier's was seven miles from town, two miles off the Maple Sugar Road that led back to Route 117.

More likely he just cut himself, Joe thought. But Christ, I hope it was just his hand he cut and not his throat.

Joe opened the screen door. It squealed on its hinges. 'Gary?'

Still no answer. There was a sickish-sweet smell in here that he didn't like. but at first he thought it was the honeysuckle. The stairs to the second floor went up on his left. Straight ahead was the hall to the kitchen, the living room doorway opening off the hall about halfway down on the right.

There was something on the hall floor but it was too dark for Joe to make it out. Looked like an endtable that had been knocked over, or something like that ... but so far as Joe knew, there wasn't now and never had been any furniture in Gary's front hall. He leaned his lawn chairs in here when it rained, but there hadn't been any rain for two weeks. Besides, the chairs had been out by Gary's Chrysler in their accustomed places. By the honeysuckle.

Only that smell wasn't honeysuckle. It was blood. A whole lot of blood. And that was no tipped-over endtable.

He hurried down to the shape, his heart hammering in his chest. He knelt by it, and a sound like a squeak escaped his throat Suddenly the air in the hall seemed too hot and dose.

It seemed to be strangling him. He turned away from Gary, one hand cupped over his mouth. Someone had murdered Gay. Someone had

He forced himself to look back. Gary lay in a pool of his own blood. His eyes glared sightlessly up at the hallway ceiling. His throat had been opened. Not just opened, dear God, it looked as if it had been chewed open.

This time there was no struggle with his gorge. This time he simply let everything come up in a series of hopeless choking sounds. Crazily, the back of his mind had turned to Charity with childish resentment. Charity had gotten her trip, but he wasn't going to get his. He wasn't going to get his because some crazy bastard had done a jack the Ripper act on poor old Gary Pervier and

- and he had to call the police. Never mind all the rest of it. Never mind the way the ole Pervert's eyes were glaring up at the ceiling in the shadows, the way the sheared-copper smell of his blood mingled with the sickish-sweet aroma of the honeysuckle.

He got to his feet and staggered down toward the kitchen. He was moaning deep in his throat but was hardly aware of it. The phone was on the wall in the kitchen. He had to call the State Police, Sheriff Bannerman, someone

ePub

ePub A4

A4