CHAPTER TEN

T

HE CEREAL BOXTHE TRUTH IS, IF YOU ASKED ME TO CHOOSE between winning the Tour de France and cancer, I would choose cancer. Odd as it sounds, I would rather have the title of cancer

survivor than winner of the Tour, because of what it has done for me as a human being, a man, a husband, a son, and a father.

In those first days after crossing the finish line in Paris I was swept up in a wave of attention, and as I struggled to keep things in perspective, I asked myself why my victory had such a

profound effect on people. Maybe it’s because illness is universal–we’ve all been sick, no one is immune–and so my winning the Tour was a symbolic act, proof that you can not only survive

cancer, but thrive after it. Maybe, as my friend Phil Knight says, I am hope.

Bill Stapleton finally convinced me that I needed to fly to New York for a day. Nike provided the private jet, and Kik came with me, and in New York, the full reach and impact of the victory

finally hit us. I had a press conference at Niketown, and the mayor did show up, and so did Donald Trump, and I appeared on the Today show, and on David Letterman. I went to Wall

Street to ring the opening bell. As I walked onto the trading floor, the traders erupted in sustained applause, stunning me. Then, as we left the building, I saw a huge throng of people

gathered on the sidewalk. I said to Bill, “I wonder what that crowd is doing here?”

“That’s for you, Lance,” Bill said. “Are you starting to get it now?”

Afterward, Kik and I went to Babies “SL” Us. People came down the aisles of the store to shake my hand and ask for autographs. I was taken aback, but Kik was unfazed. She just said, blithely,

“I think we need some onesies and a diaper pail.”

To us, there was a more ordinary act of survival still to come: parenthood.

AT FIRST, I WORRIED THAT BECAUSE I DIDN’T HAVE A

relationship with my own father, I might not make a good one myself.

I tried to practice being a father. I bought a sling to carry the baby in, and I wore it around the house, empty. I strapped it on and wore it in the kitchen while I made breakfast. I kept it on

when I sat in my office, answering mail and returning phone calls. I strolled in the backyard with it on, imagining that a small figure was nestled there.

Kik and I went to the hospital for a tour of the facilities and a nurse briefed us on what to expect when Kik went into labor.

“After the baby is delivered it will be placed on Kristin’s chest,” she said. “Then we will cut the umbilical cord.”

“I’ll cut the umbilical cord,” I said.

“All right,” the nurse said agreeably. “Next, a nurse will bathe the baby …”

“I’ll bathe the baby.”

“Fine,” the nurse said. “After that, we will carry the baby down the hall . ..”

“I’ll carry the baby,” I said. “It’s my baby.”

One afternoon late in her pregnancy, Kik and I were running errands in separate cars, and I ended up tailgating her home. I thought she was driving too fast, so I dialed her number on the

car phone.

“Slow it down,” I said. “That’s my child you’re carrying.”

In those last few weeks of her pregnancy, Kik liked to tell people, “I’m expecting my second child.”

In early October, about two weeks before the baby was due, Bill Stapleton and I went to Las Vegas, where I was to deliver a speech and hold a couple of business meetings. When I called

home, Kik told me she was sweating and felt strange, but I didn’t think much about it at first. I went on with my business, and when I was done, Bill and I dashed to catch an afternoon flight

back to Dallas, with an evening connection to Austin.

In a private lounge area in Dallas I called Kik, and she said she was still sweating, and now she was having contractions.

“Come on,” I said. “You’re not really having this baby, are you? It’s probably a false alarm.”

On the other end of the line, Kik said, “Lance, this is not funny.”

Then she went into a contraction.

“Okay, okay,” I said. “I’m on my way.”

We boarded the plane for Austin, and as we took our seats, Staple-ton said, “Let me give you a little marital advice. I don’t know if your wife’s having a baby tonight, but we need to call her

again when we get up in the air.”

The plane began its taxi, but I was too impatient to wait for takeoff, so I called her from the runway on my cell phone.

“Look, what’s going on?” I said.

“My contractions are a minute long, and they’re five minutes apart, and they’re getting longer,” she said.

“Kik, do you think we’re having this baby tonight?”

“Yeah, I think we’re having the baby tonight.”

“I’ll call you as soon as we land.”

I hung up, and ordered two beers from the flight attendant, and Bill and I clinked bottles and toasted the baby. It was just a 40-minute flight to Austin, but my leg jiggled the whole way

there. As soon as landed, I called her again. Usually, when Kik answers the phone she says “Hi!” with a voice full of enthusiasm. But this time she picked up with a dull “Hi.”

“How you feeling, babe?” I said, trying to sound calm.

“Not good.”

“How we doing?”

“Hold on,” she said.

She had another contraction. After a minute she got back on.

“Have you called the doctor?” I said.

“Yeah.”

“What’d he say?”

“He said to come into the hospital as soon as you get home.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll be there.”

I floored it. I drove 105 in a 35 zone. I screeched into the driveway, helped Kik into the car, and then drove more carefully to St. David’s Hospital, the same place where I had my cancer

surgery.

Forget what they tell you about the miracle of childbirth, and how it’s the greatest thing that

ever happens to you. It was horrible, terrifying, one of the worst nights of my life, because I was so worried for Kik, and for our baby, for all of us.

Kik had been in labor for three hours as it turned out, and when the delivery-room staff took a look at her and told me how dilated she was, I told her, “You’re a stud.” What’s more, the baby

was turned “sunny side up,” with its face toward her tailbone, so she had racking pains in her back.

The baby was coming butt-first, and Kik had trouble delivering. She tore, and she bled, and then the doctor said, “We’re going to have to use the vacuum.” They brought out something that

practically looked like a bathroom plunger, and they attached it to my wife. They performed a procedure, and–and the baby popped right out. It was a boy. Luke David Armstrong was

officially born.

When they pulled him out he was tiny, and blue, and covered with birth fluids. They placed him on Kik’s chest, and we huddled together. But he wasn’t crying. He just made a couple of small,

mew-like sounds. The delivery-room staff seemed concerned that he wasn’t making more noise. Cry, I thought. Another moment passed, and still Luke didn’t cry. Come on, cry. I could feel the

room grow tense around me.

“He’s going to need a little help,” someone said.

They took him away from us.

A nurse whisked the baby out of Kik’s arms and around a corner into another room, full of complicated equipment.

Suddenly, people were running.

“What’s wrong?” Kik said. “What’s happening?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

Medical personnel dashed in and out of the room, as if it was an emergency. I held Kik’s hand and I craned my neck, trying to see what was going on in the next room. I couldn’t see our baby.

I didn’t know what to do. My son was in there, but I didn’t want to leave Kik, who was terrified. She kept saying to me, “What’s going on, what are they doing to him?” Finally, I let go

of her hand and peered around the corner.

They had him on oxygen, with a tiny mask over his face.

Cry, please. Please, please cry.

I was petrified. At that moment I would have done anything just to hear him scream, absolutely

anything. Whatever I knew about fear was completely eclipsed in that delivery room. I was scared when I was diagnosed with cancer, and I was scared when I was being treated, but it was

nothing compared to what I felt when they took our baby away from us. I felt totally helpless, because this time it wasn’t me who was sick, it was somebody else. It was my son.

They removed the mask. He opened his mouth, and scrunched his face, and all of a sudden he let out a big, strong “Whaaaaaaaaaa!!!” He screamed like a world-class, champion screamer.

With that, his color changed, and everyone seemed to relax. They brought him back to us. I held him, and I kissed him.

I bathed him, and the nurse showed me how to swaddle him, and together, Kik and Luke and I went to a large hospital room that was almost like a hotel suite. It had the regulation hospital

bed and equipment, but it also had a sofa and a coffee table for visitors. We slept together for a few hours, and then everyone began to arrive. My mother came, and Kik’s parents, and Bill and

Laura Stapleton. That first evening, we had a pizza party. Visitors stuck their heads in our door to see Kik sitting up in bed sipping a Shiner Bock and chewing on a slice.

My mother and I took a stroll through the corridors, and I couldn’t help thinking about what I had just gone through with Luke. I completely understood now what she must have felt when it

seemed as though she might outlive her own child.

We passed by my old hospital room. “Remember that?” I asked. We smiled at each other.

THE QUESTION THAT LINGERS IS, HOW MUCH WAS I A

factor in my own survival, and how much was science, and how much miracle?

I don’t have the answer to that question. Other people look to me for the answer, I know. But if I could answer it, we would have the cure for cancer, and what’s more, we would fathom the

true meaning of our existences. I can deliver motivation, inspiration, hope, courage, and counsel, but I can’t answer the unknowable. Personally, I don’t need to try. I’m content with simply being

alive to enjoy the mystery.

Good joke:

A man is caught in a flood, and as the water rises he climbs to the roof of his house and waits to be rescued. A guy in a motorboat comes by, and he says, “Hop in, I’ll save you.”

“No, thanks,” the man on the rooftop says. “My Lord will save me.”

But the floodwaters keep rising. A few minutes later, a rescue plane flies overhead and the pilot drops a line.

“No, thanks,” the man on the rooftop says. “My Lord will save me.”

But the floodwaters rise ever higher, and finally, they overflow the roof and the man drowns.

When he gets to heaven, he confronts God.

“My Lord, why didn’t you save me?” he implores.

“You idiot,” God says. “I sent you a boat, I sent you a plane.”

I think in a way we are all just like the guy on the rooftop. Things take place, there is a confluence of events and circumstances, and we can’t always know their purpose, or even if

there is one. But we can take responsibility for ourselves and be brave.

We each cope differently with the specter of our deaths. Some people deny it. Some pray. Some numb themselves with tequila. I was tempted to do a little of each of those things. But I think

we are supposed to try to face it straightforwardly, armed with nothing but courage. The definition of courage is: the quality of spirit that enables one to encounter danger with firmness

and without fear.

It’s a fact that children with cancer have higher cure rates than adults with cancer, and I wonder if the reason is their natural, unthinking bravery. Sometimes little kids seem better equipped to

deal with cancer than grown-ups are. They’re very determined little characters, and you don’t have to give them big pep talks. Adults know too much about failure; they’re more cynical and

resigned and fearful. Kids say, “I want to play. Hurry up, and make me better.” That’s all they want.

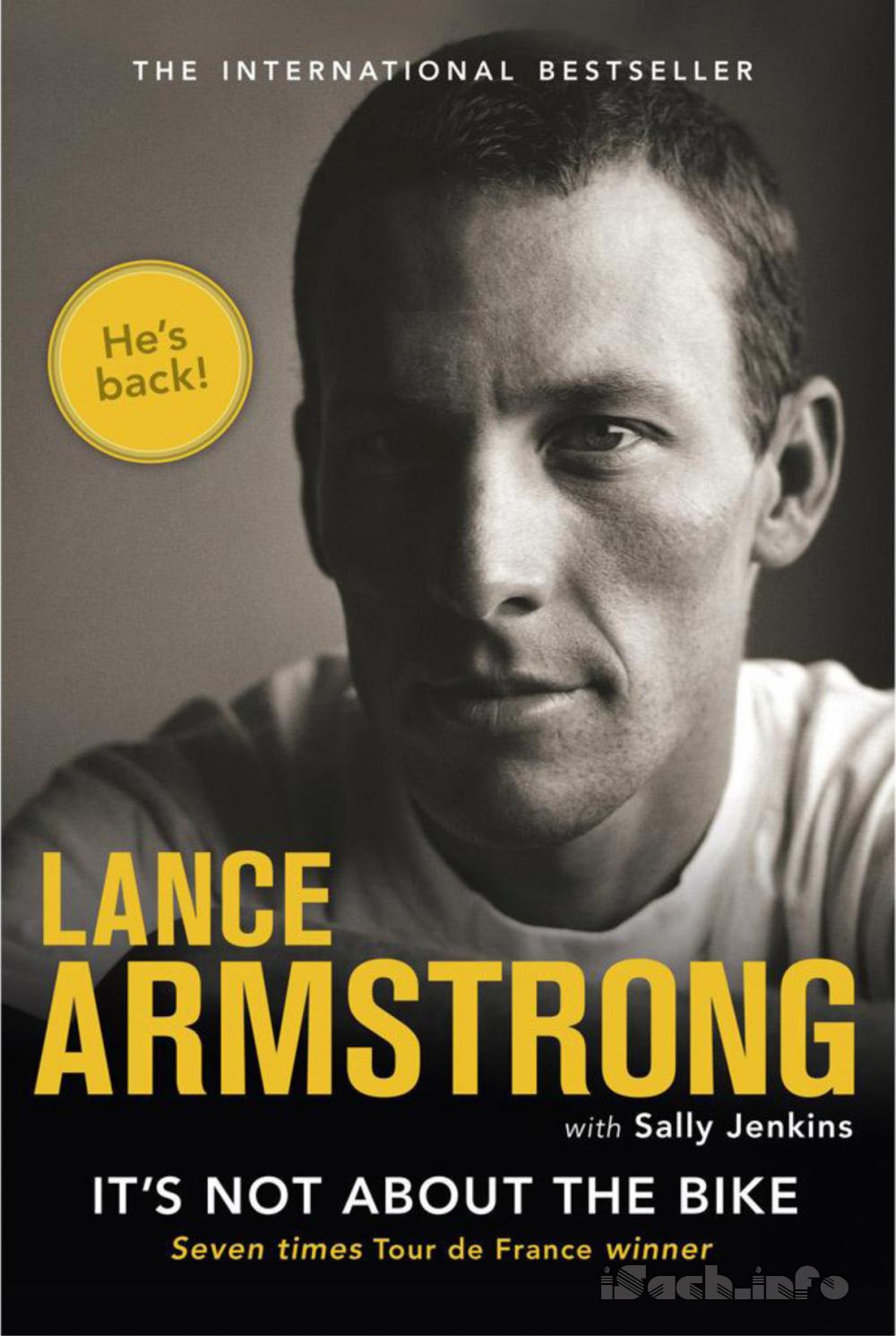

When Wheaties decided to put me on the cover of the box after the Tour de France, I asked if we could hold the press conference in the children’s cancer ward at the same hospital where my

son was born. As I visited with the kids and signed some autographs, one little boy grabbed a Wheaties box and stood at my knees, clutching it to his chest.

“Can I have this?” he said.

“Yeah, you can have it,” I said. “It’s yours.”

He just stood there, looking at the box, and then he looked back at me. I figured he was pretty impressed.

Then he said, “What shapes are they?”

“What?” I said.

“What shapes are they?”

“Well,” I said, “it’s cereal. It’s all different shapes.”

“Oh,” he said. “Okay.”

See, to him, it’s not about cancer. It’s just about cereal.

IF CHILDREN HAVE THE ABILITY TO IGNORE ODDS AND

percentages, then maybe we can all learn from them. When you think about it, what other choice is there but to hope? We have two options, medically and emotionally: give up, or fight

like hell.

After I was well again, I asked Dr. Nichols what my chances really were. “You were in bad shape,” he said. He told me I was one of the worst cases he had seen. I asked, “How bad was I?

Worst fifty percent?” He shook his head. “Worst twenty percent?” He shook his head again. “Worst ten?” He still shook his head.

When I got to three percent, he started nodding.

Anything’s possible. You can be told you have a 90-percent chance or a 50-percent chance or a 1-percent chance, but you have to believe, and you have to fight. By fight I mean arm yourself

with all the available information, get second opinions, third opinions, and fourth opinions. Understand what has invaded your body, and what the possible cures are. It’s another fact of

cancer that the more informed and empowered patient has a better chance of long-term survival.

What if I had lost? What if I relapsed and the cancer came back? I still believe I would have gained something in the struggle, because in what time I had left I would have been a more

complete, compassionate, and intelligent man, and therefore more alive. The one thing the illness has convinced me of beyond all doubt–more than any experience I’ve had as an athlete–is

that we are much better than we know. We have unrealized capacities that sometimes only emerge in crisis.

So if there is a purpose to the suffering that is cancer, I think it must be this: it’s meant to improve us.

I am very firm in my belief that cancer is not a form of death. I choose to redefine it: it is a part of life. One afternoon when I was in remission and sitting around waiting to find out if the

cancer would come back, I made an acronym out of the word: Courage, Attitude, Never give up, Curability, Enlightenment, and Remembrance of my fellow patients.

In one of our talks, I asked Dr. Nichols why he chose oncology, a field so difficult and

heartbreaking. “Maybe for some of the same reasons you do what you do,” he said. In a way, he suggested, cancer is the Tour de France of illnesses.

“The burden of cancer is enormous, but what greater challenge can you ask?” he said. “There’s no question it’s disheartening and sad, but even when you don’t cure people, you’re always

helping them. If you’re not able to treat them successfully, at least you can help them manage the illness. You connect with people. There are more human moments in oncology than any

other field I could imagine. You never get used to it, but you come to appreciate how people deal with it–how strong they are.”

“You don’t know it yet, but we’re the lucky ones,” my fellow cancer patient had written.

I will always carry the lesson of cancer with me, and feel that I’m a member of the cancer community. I believe I have an obligation to make something better out of my life than before,

and to help my fellow human beings who are dealing with the disease. It’s a community of shared experience. Anyone who has heard the words You have cancer and thought, “Oh, my

God, I’m going to die,” is a member of it. If you’ve ever belonged, you never leave.

So when the world seems unpromising and gray, and human nature mean, I take out my driver’s license and I stare at the picture, and I think about LaTrice Haney, Scott Shapiro, Craig Nichols,

Lawrence Einhorn, and the little boy who likes cereal for their shapes. I think about my son, the embodiment of my second life, who gives me a purpose apart from myself.

Sometimes, I wake up in the middle of the night and I miss him. I lift him out of his crib and I take him back to bed with me, and I lay him on my chest. Every cry of his delights me. He

throws back his tiny head and his chin trembles and his hands claw the air, and he wails. It sounds like the wail of life to me. “Yeah, that’s right,” I urge him. “Go on.”

The louder he cries, the more I smile.

ePub

ePub A4

A4