Chapter 7

W

HEN I WOKE TO the clatter of garbage trucks, it was as if I’d parachuted into a different universe. My throat hurt. Lying very still under the eiderdown, I breathed the dark air of dried-out potpourri and burnt fireplace wood and—very faint—the evergreen tang of turpentine, resin, and varnish.For some time I lay there. Popper—who’d been curled by my feet—was nowhere in evidence. I’d slept in my clothes, which were filthy. At last—propelled by a sneezing fit—I sat up, pulled my sweater over my shirt and grappled under the bed to make sure the pillowcase was still there, then trudged on cold floors to the bathroom. My hair had dried in knots too tangled to yank the comb through, and even after I doused it in water and started over, one chunk was so matted I finally gave up and sawed it out, laboriously, with a pair of rusted nail scissors from the drawer.

Christ, I thought, turning from the mirror to sneeze. I hadn’t been around a mirror in a while and I barely recognized myself: bruised jaw, spattering of chin acne, face blotched and swollen from my cold—eyes swollen too, lidded and sleepy, giving me a sort of dumb, shifty, homeschooled look. I looked like some cult-raised kid just rescued by local law enforcement, brought blinking from some basement stocked with firearms and powdered milk.

It was late: nine. Stepping out of my room, I could hear the morning classical program on WNYC, a dream familiarity in the announcer’s voice, Köchel numbers, a drugged calm, the same warm public-radio purr I’d woken up to so many mornings back at Sutton Place. In the kitchen, I found Hobie at the table with a book.

But he wasn’t reading; he was staring across the room. When he saw me he started.

“Well, there you are,” he said as he rose to messily sweep aside a pile of mail and bills so I could sit. He was dressed for the workshop, knee-sprung corduroys and an old peat-brown sweater, ragged and eaten with moth holes, and his receding hairline and new short-cropped hair gave him the ponderous, bald-templed look of the marble senator on the cover of Hadley’s Latin book. “How’s the form?”

“Fine, thanks.” Voice gravelled and croaking.

Down came the brows again and he looked at me hard. “Good heavens!” he said. “You sound like a raven this morning.”

What did that mean? Ablaze with shame, I slid into the chair he scraped out for me and—too embarrassed to meet his eye—stared at his book: cracked leather, Life and Letters of Lord Somebody, an old volume that had probably come from one of his estate sales, old Mrs. So-and-So up in Poughkeepsie, broken hip, no children, all very sad.

He was pouring me tea, pushing a plate my way. In an attempt to hide my discomfort I put my head down and plowed into the toast—and nearly choked, since my throat was too raw for me to swallow. Too quickly I reached for the tea, so I sloshed it on the tablecloth and had to scramble to blot it up.

“No—no, it doesn’t matter—here—”

My napkin was sopping wet; I didn’t know what to do with it; in my confusion I dropped it on top of my toast and reached under my glasses to rub my eyes. “I’m sorry,” I blurted.

“Sorry?” He was looking at me as if I’d asked him for directions to a place he wasn’t sure how to get to. “Oh, come now—”

“Please don’t make me go.”

“What’s that? Make you go? Go where?” He pulled his half-moon glasses low and looked at me over the tops of them. “Don’t be ridiculous,” he said, in a playful, half-irritated voice. “Tell you where I ought to make you go is straight back to bed. You sound like you’re down with the Black Death.”

But his manner failed to reassure me. Paralyzed with embarrassment, determined not to start crying, I found myself staring hard at the forlorn spot by the stove where once upon a time Cosmo’s basket had stood.

“Ah,” said Hobie, when he saw me looking at the empty corner. “Yes. There you go. Deaf as a haddock, having three and four seizures a week but still we wanted him to live forever. I blubbed like a baby. If you’d told me Welty was going to go before Cosmo—he spent half his life carrying that dog back and forth to the vet—Look here,” he said in an altered voice, leaning forward and trying to catch my eye when still I sat speechless and miserable. “Come on. I know you’ve been through a lot but there’s no need in the world to fuss about it now. You look very shook—now, now, yes you do,” he said crisply. “Very shook indeed and—bless you!”—flinching a bit—“bad dose of something, for sure. Don’t fret—everything’s all right. Go back to bed, why don’t you, and we’ll hash it out later.”

“I know but—” I turned my head away to stifle a wet, burbling sneeze. “I don’t have any place to go.”

He leaned back in his chair: courteous, careful, something a little dusty about him. “Theo—” tapping at his lower lip—“how old are you?”

“Fifteen. Fifteen and a half.”

“And—” he seemed to be working out how to ask it—“what about your grandfather?”

“Oh,” I said, helplessly, after a pause.

“You’ve spoken to him? He knows that you’ve nowhere to go?”

“Well, shit—” it had just slipped out; Hobie put up a hand to reassure me—“you don’t understand. I mean—I don’t know if he has Alzheimer’s or what, but when they called him he didn’t even ask to speak to me.”

“So—” Hobie leaned his chin heavily in his hand and eyed me like a skeptical schoolteacher—“you didn’t speak to him.”

“No—I mean not personally—this lady was there, helping out—” Xandra’s friend Lisa (solicitous, following me around, voicing gentle but increasingly urgent concerns that “the family” be notified) had retreated to a corner at some point to dial the number I gave her—and got off the phone with such a look that it had elicited, from Xandra, the only laugh of the evening.

“This lady?” said Hobie, in the silence that had fallen, in a voice you might employ with a mental patient.

“Right. I mean—” I scrubbed a hand over my face; the colors in the kitchen were too intense; I felt lightheaded, out of control—“I guess Dorothy answered the phone and Lisa said she was like ‘okay, wait,’—not even ‘Oh no!’ or ‘what happened?’ or ‘how terrible!’—just ‘hang on, let me get him,’ and then my granddad came on and Lisa told him about the wreck and he listened, and then he said well, he was sorry to hear it, but in this sort of tone, Lisa said. Not ‘what can I do’ or ‘when is the funeral’ or anything. Just, like, thank you for calling, we appreciate it, bye. I mean—I could have told her,” I added nervously when Hobie didn’t answer. “Because, I mean, they really didn’t like my dad—really didn’t like him—Dorothy is his stepmother and they hated each other from Day One but he never got along with Grandpa Decker either—”

“All right, all right. Steady on—”

“—and, I mean, my dad was in some trouble when he was a kid, that might have had something to do with it—he was arrested but I don’t know what for—honestly I don’t know why, but they never wanted anything to do with him for as long as I remember and they never wanted anything to do with me either—”

“Calm down! I’m not trying to—”

“—because, I swear, I hardly ever met them, I really don’t know them at all but there’s no reason for them to hate me—not that my grandpa is such a great guy, he was pretty abusive to my dad actually—”

“Ssh—no carrying on! I’m not trying to put the screws on you, I just want to know—no now, listen,” he said as I tried to talk over him, batting away my words as if he were shooing a fly from the table.

“My mother’s lawyer is here. In the city. Will you come with me to see him? No,” I said in confusion as his eyebrows came together, “not a lawyer lawyer, but that handles money? I talked to him on the phone? Before I left?”

“Okay,” said Pippa—laughing, pink-cheeked from the cold—“what’s wrong with this dog? Has he never seen a car?”

Bright red hair; green wool hat; the shock of seeing her in broad daylight was a dash of cold water. She had a hitch in her walk, probably from the accident but there was a grasshopper lightness to it like the odd, graceful preliminary to a dance step; and she was wrapped in so many layers against the cold that she looked like a colorful little cocoon, with feet.

“He was yowling like a cat,” she said, unwinding one of her many patterned scarves as Popchyk danced at her feet with the end of his leash in his mouth. “Does he always make that weird noise? I mean, a cab would go by and—whoo! in the air! I was flying him like a kite! People were laughing their heads off. Yes—” stooping to speak to the dog, rubbing the top of his head with her knuckles—“you, you need a bath, don’t you? Is he a Maltese?” she said, glancing up.

Furiously I nodded, back of my hand to my mouth, trying to choke back a sneeze.

“I love dogs.” I could hardly hear what she was saying, so dazzled was I by her eyes on mine. “I have a dog book and I memorized every breed there is. If I had a big dog I’d have a Newfoundland like Nana in Peter Pan, and if I had a small dog—well, I change my mind all the time. I like all the little terriers—Jack Russells especially, they’re always so funny and friendly on the street. But I know a wonderful Basenji too. And I met a really great Pekingese the other day. Really really tiny and really intelligent. Only royalty could have them in China. They’re a very ancient breed.”

“Maltese are ancient, too,” I croaked, glad to have an interesting fact to contribute. “They date back to ancient Greece.”

“That’s why you picked a Maltese? Because it was ancient?”

“Um—” Stifling a cough.

She was saying something else—to the dog, not me—but I’d fallen into another fit of sneezing. Quickly, Hobie scrabbled for the closest thing at hand—a table napkin—and passed it over to me.

“All right, enough,” he said. “Back to bed. No, no,” he said as I tried to hand the napkin back to him, “you keep it. Now tell me—” eyeing my wrecked plate, spilled tea and soggy toast—“what can I bring you for breakfast?”

Caught between sneezes, I gave a bright, Russian-accented shrug I’d picked up from Boris: anything.

“All right then, if you don’t mind it, I’ll make you some oatmeal. Easy on the throat. Don’t you have any socks?”

“Um—” She was busy with the dog, mustard-yellow sweater and hair like an autumn leaf, and her colors were mixed up and confused with the bright colors of the kitchen: striped apples glowing in a yellow bowl, the sharp ding of silver glinting from the coffee can where Hobie kept his paintbrushes.

“Pyjamas?” Hobie was saying. “No? I’ll see what I can find of Welty’s. And when you get out of those things I’ll throw them in the wash. Now, off with you,” he said, clapping his hand on my shoulder so suddenly I jumped.

“I—”

“You can stay. As long as however you like. And don’t worry, I’ll go with you to see your solicitor, it’ll all be fine.”

ii.

GROGGY, SHIVERING, I MADE my way down the dark hall and eased between the covers, which were heavy and ice-cold. The room smelled damp, and though there were many interesting things to look at—a pair of terra-cotta griffins, Victorian beadwork pictures, even a crystal ball—the dark brown walls, their deep dry texture like cocoa powder, soaked me through and through with a sense of Hobie’s voice and also of Welty’s, a friendly brown that saturated me to the core and spoke in warm old-fashioned tones, so that drifting in a lurid stream of fever I felt wrapped and reassured by their presence whereas Pippa had cast a shifting, colored nimbus of her own, I was thinking in a mixed-up way about scarlet leaves and bonfire sparks flying up in darkness and also my painting, how it would look against such a rich, dark, light-absorbing ground. Yellow feathers. Flash of crimson. Bright black eyes.

I woke with a jolt—terrified, flailing, back on the bus again with someone lifting the painting from my knapsack—to find Pippa lifting up the sleepy dog, her hair brighter than everything else in the room.

“Sorry, but he needs to go out,” she said. “Don’t sneeze on me.”

I scrambled up on my elbows. “Sorry, hi,” I said idiotically, smearing an arm across my face; and then: “I’m feeling better.”

Her unsettling golden-brown eyes went around the room. “Are you bored? Do you want me to bring you some colored pencils?”

“Colored pencils?” I was baffled. “Why?”

“Uh, to draw with—?”

“Well—”

“Not a big deal,” she said. “All you had to say was no.”

Out she whisked, Popchik trotting after her, leaving behind her a smell of cinnamon gum, and I turned my face into the pillow feeling crushed by my stupidity. Though I would have died rather than told anyone, I was worried that my exuberant drug use had damaged my brain and my nervous system and maybe even my soul in some irreparable and perhaps not readily apparent way.

While I was lying there worrying, my cell phone beeped: GES WR I AM? POOL @ MGM GRAND!!!!!

I blinked. BORIS? I texted in reply.

YES, IS ME!

What was he doing there? RUOK? I texted back.

YES BT V SLEEPY! WE BIN DOIN THOS 8BALS OMG:-)

And then, another ding:

* GREAT * FUN. PARTY PARTY. U? LIVING UNDER UNDRPASS?

NYC, I texted back. SICK IN BED. WHY RU AT MGMGR

HERE W KT AND AMBER & THOSE GUYS!!!;-)

then, coming in a second later: DO U NO OF DRINK CALLED WITE RUSIAN? V NICE TASTNG NOT V GOOD NAME 4 DRNK THO

A knock. “Are you all right?” said Hobie, sticking his head in the door. “Can I bring you anything?”

I put the phone aside. “No, thank you.”

“Well, tell me when you’re hungry, please. There’s loads of food, the fridge is so stuffed I can hardly get the door closed, we had people in for Thanksgiving—what is that racket?” he said, looking around.

“Just my phone.” Boris had texted: U CANT BELIEVE THE LAST FEW DAZE!!!

“Well, I’ll leave you to it. Let me know if you need something.”

Once he was gone, I rolled to face the wall and texted back: MGMGR? W/ KT BEARMAN?!

The answer came almost immediately: YES! ALSO AMBER & MIMI & JESICA & KT’S SISTR JORDAN WHO IS IN *COLEGE*:-D

WTF???

U LEFT AT A BAD TIME!!!:-D

then, almost immediately, before I could reply: G2GO, AMBR NEEDS HER PHONE

CALL ME L8R, I texted back. But there was no reply—and it would be a long, long time before I heard anything from Boris again.

iii.

THAT DAY, AND THE next day or two, flopping around in a bewilderingly soft pair of Welty’s old pyjamas, were so topsy-turvy and deranged with fever that repeatedly I found myself back at Port Authority running away from people, dodging through crowds and ducking into tunnels with oily water dripping on me or else in Las Vegas again on the CAT bus, riding through windwhipped industrial plazas with blown sand hitting the windows and no money to pay my fare. Time slid from under me in drifts like ice skids on the highway, punctuated by sudden sharp flashes where my wheels caught and I was flung into ordinary time: Hobie bringing me aspirins and ginger ale with ice, Popchik—freshly bathed, fluffy and snow-white—hopping up on the foot of the bed to march back and forth across my feet.

“Here,” said Pippa, coming over to the bed and poking me in the side so she could sit down. “Move over.”

I sat up, fumbling for my glasses. I’d been dreaming about the painting—I’d had it out, looking at it, or had I?—and found myself glancing around anxiously to make sure I’d put it away before I went to sleep.

“What’s the matter?”

I forced myself to turn my gaze to her face. “Nothing.” I’d crawled under the bed several times just to put my hands on the pillowcase, and I couldn’t help wondering if I’d been careless and left it poking from under the bed. Don’t look down there, I told myself. Look at her.

“Here,” Pippa was saying. “Made you something. Hold out your hand.”

“Wow,” I said, staring at the spiked, kelly-green origami in my palm. “Thanks.”

“Do you know what it is?”

“Uh—” Deer? Crow? Gazelle? Panicked, I glanced up at her.

“Give up? A frog! Can’t you tell? Here, put it on the nightstand. It’s supposed to hop when you press on it like this, see?”

As I fooled around with it, awkwardly, I was aware of her eyes on me—eyes that had a light and wildness to them, a careless power like the eyes of a kitten.

“Can I look at this?” She’d snatched up my iPod and was busily scrolling through it. “Hmn,” she said. “Nice! Magnetic Fields, Mazzy Star, Nico, Nirvana, Oscar Peterson. No classical?”

“Well, there’s some,” I said, feeling embarrassed. Everything she’d mentioned except the Nirvana had actually been my mom’s, and even some of that was hers.

“I’d make you some CDs. Except I left my computer at school. I guess I could mail you some—I’ve been listening to a lot of Arvo Pärt lately, don’t ask me why, I have to listen on my headphones because it drives my roommates nuts.”

Terrified she was going to catch me staring, unable to wrench my eyes away, I watched her studying my iPod with bent head: ears rosy-pink, raised line of scar tissue slightly puckered underneath the scalding-red hair. In profile her downcast eyes were long, heavy-lidded, with a tenderness that reminded me of the angels and page boys in the Northern European Masterworks book I’d checked and re-checked from the library.

“Hey—” Words drying up in my mouth.

“Yes?”

“Um—” Why wasn’t it like before? Why couldn’t I think of anything to say?

“Oooh—” she’d glanced up at me, and then was laughing again, laughing too hard to talk.

“What is it?”

“Why are you looking at me like that?”

“Like what?” I said, alarmed.

“Like—” I wasn’t sure how to interpret the pop-eyed face she made at me. Choking person? Mongoloid? Fish?

“Dont be mad. You’re just so serious. It’s just—” she glanced down at the iPod, and broke out laughing again. “Ooh,” she said, “Shostakovich, intense.”

How much did she remember? I wondered, afire with humiliation yet unable to tear my eyes from her. It wasn’t the kind of thing you could ask but still I wanted to know. Did she have nightmares too? Crowd fears? Sweats and panics? Did she ever have the sense of observing herself from afar, as I often did, as if the explosion had knocked my body and my soul into two separate entities that remained about six feet apart from one another? Her gust of laughter had a self-propelling recklessness I knew all too well from wild nights with Boris, an edge of giddiness and hysteria that I associated (in myself, anyway) with having narrowly missed death. There had been nights in the desert where I was so sick with laughter, convulsed and doubled over with aching stomach for hours on end, I would happily have thrown myself in front of a car to make it stop.

iv.

ON MONDAY MORNING, THOUGH I was far from well, I roused myself from my fog of aches and dozes and trudged dutifully into the kitchen and telephoned Mr. Bracegirdle’s office. But when I asked for him, his secretary (after putting me on hold, and then returning a bit too swiftly) informed me that Mr. Bracegirdle was out of the office and no, she didn’t have a number where he could be reached and no, she was afraid she couldn’t say when he might be in. Was there anything else?

“Well—” I left Hobie’s number with her and was regretting that I’d been too slow on the draw to go ahead and schedule the appointment when the phone rang.

“212, eh?” said the rich, clever voice.

“I left,” I said stupidly; the cold in my head made me sound nasal and block-witted. “I’m in the city.”

“Yes, I gathered.” His tone was friendly but cool. “What can I do for you?”

When I told him about my father, there was a deep breath. “Well,” he said carefully. “I’m sorry to hear it. When did this happen?”

“Last week.”

He listened without interrupting; in the five minutes or so it took me to fill him in, I heard him turn away at least two other calls. “Crikey,” he said, when I’d finished talking. “That’s quite a story, Theodore.”

Crikey: in a different mood, I might have smiled. This was definitely a person my mother had known and liked.

“It must have been dreadful for you out there,” he was saying. “Of course, I’m terribly sorry for your loss. It’s all very sad. Though quite frankly—and I feel more comfortable saying this to you now—when he turned up, no one knew what to do. Your mother had of course confided some things—even Samantha had expressed concerns—well, as you know, it was a difficult situation. But I don’t think anyone expected this. Thugs with baseball bats.”

“Well—” thugs with baseball bats, I hadn’t really meant for him to seize on that detail. “He was just standing there holding it. It’s not like he hit me or anything.”

“Well—” he laughed, an easy laugh that broke the tension—“sixty-five thousand dollars did seem like a very specific sum. I have to say too—I went a bit beyond my authority as your counsel when we spoke on the phone, though under the circumstances I hope you’ll forgive me. It was just that I smelled a bit of a rat.”

“Sorry?” I said, after a sick pause.

“Over the phone. The money. You can withdraw it, from the 529 anyway. Large tax penalty, but it’s possible.”

Possible? I could have taken it? An alternate future was flashing through my mind: Mr. Silver paid, Dad in his bathrobe checking the sports scores on his BlackBerry, me in Spirsetskaya’s class with Boris lazing across the aisle from me.

“Although I do need to tell you that the money in the fund is actually a bit short of that,” Mr. Bracegirdle was saying. “Socked away and growing all the time, though! Not that we can’t arrange for you to use some of it now, given your circumstances, but your mother was absolutely determined not to dip into it even with her financial troubles. The last thing she would have wanted was for your dad to get his hands on it. And yes, just between the two of us, I do think you were very smart to come back to the city on your own recognizance. Sorry—” muffled conversation—“I’ve got an eleven o’clock, I’ve got to run—you’re staying at Samantha’s now, I gather?”

The question threw me for a loop. “No,” I said, “with some friends in the Village.”

“Well, splendid. Just so long as you’re comfortable. At any rate, I’m afraid I have to dash now. What do you say we continue this discussion in my office? I’ll put you back through to Patsy so she can schedule an appointment.”

“Great,” I said, “thank you,” but when I got off the phone, I felt sick—like someone had just reached a hand in my chest and wrenched loose a lot of ugly wet stuff around my heart.

“Everything okay?” said Hobie—crossing through the kitchen, stopping suddenly to see the look on my face.

“Sure.” But it was a long walk down the hall to my room—and once I closed the door and climbed back in bed I began to cry, or half-cry, ugly dry wheezes with my face pressed in the pillow, while Popchik pawed at my shirt and snuffled anxiously against the back of my neck.

v.

BEFORE THIS, I’D BEEN feeling better, but somehow it was like this news made me ill all over again. As the day wore on and my fever climbed to its former dizzying wobble, I could think of nothing but my dad: I have to call him, I thought, starting again and again from bed just as I was drifting off; it was as if his death weren’t real but only a rehearsal, a trial run; the real death (the permanent one) was yet to happen and there was time to stop it if only I found him, if only he was answering his cell phone, if Xandra could reach him from work, I have to get hold of him, I have to let him know. Then, later—the day was over, it was dark—I had fallen into a troubled half dream where my dad was excoriating me for screwing up some air travel reservations when I became aware of lights in the hallway, a tiny backlit shadow—Pippa, coming suddenly into the room with stumbling step almost like someone had pushed her, looking doubtfully behind her, saying: “Should I wake him?”

“Wait,” I said—half to her and half to my dad, who was falling back rapidly into the darkness, some violent stadium crowd on the other side of a tall, arched gate. When I got my glasses on, I saw she had her coat on like she was going out.

“Sorry?” I said, arm over my eyes, confused in the glare from the lamp.

“No, I’m sorry. It’s just—I mean—” pushing a strand of hair out of her face—“I’m leaving and I wanted to say goodbye.”

“Goodbye?”

“Oh.” Her pale brows drew together; she looked in the doorway to Hobie (who had vanished) and back to me. “Right. Well.” Her voice seemed slightly panicked. “I’m going back. Tonight. Anyway, it was nice to see you. I hope everything works out for you okay.”

“Tonight?”

“Yeah, I’m flying out now. She has me in boarding school?” she said when I continued to goggle at her. “I’m here for Thanksgiving? Here to see the doctor? Remember?”

“Oh. Right.” I was staring at her very hard and hoping that I was still asleep. Boarding school rang a vague bell but I thought it was something I’d dreamed.

“Yeah—” she seemed uneasy too—“too bad you didn’t get here earlier, it was fun. Hobie cooked—we had tons of people over. Anyway I was lucky I got to come at all—I had to get permission from Dr. Camenzind. We don’t have Thanksgiving off at my school.”

“What do they do?”

“They don’t celebrate it. Well—I think maybe they make turkey or something for the people who do.”

“What school is this?”

When she told me the name—with a half-humorous quirk of her mouth—I was shocked. Institut Mont-Haefeli was a school in Switzerland—barely accredited, according to Andy—where only the very dumbest and most disturbed girls went.

“Mont-Haefeli? Really? I thought it was very”—the word psychiatric was wrong—“wow.”

“Well. Aunt Margaret says I’ll get used to it.” She was fooling around with the origami frog on the nightstand, trying to make it jump, only it was bent and tipping to one side. “And the view is like the mountain on the Caran d’Ache box. Snowcaps and flower meadow and all that. Otherwise it’s like one of those dull Euro horror movies where nothing much happens.”

“But—” I felt like I was missing something, or maybe still asleep. The only person I’d ever known who went to Mont-Haefeli was James Villiers’s sister, Dorit Villiers, and the story was she’d been sent there because she stabbed her boyfriend in the hand with a knife.

“Yeah, it’s a weird place,” she said, bored eyes flickering around the room. “A school for loonies. Not many places I could get in with my head injury though. They have a clinic attached,” she said, shrugging. “Doctors on staff. Bigger deal than you’d think. I mean, I have problems since I got hit on the head, but it’s not like I’m nuts or a shoplifter.”

“Yeah, but—” I was still trying to get horror movie out of my mind—“Switzerland? That’s pretty cool.”

“If you say so.”

“I knew this girl Lallie Foulkes who went to Le Rosey. She said they had a chocolate break every morning.”

“Well, we don’t even get jam on our toast.” Her hand was speckled and pale against the black of her coat. “Only the eating-disorder girls get it. If you want sugar in your tea you have to steal the packets from the nurses’ station.”

“Um—” Worse and worse. “Do you know a girl named Dorit Villiers?”

“No. She was there but then they sent her someplace else. I think she tried to scratch somebody in the face. They had her in lock-up for a while.”

“What?”

“That’s not what they call it,” she said, rubbing her nose. “It’s a farm-looking building they call La Grange—you know, all milkmaid and fake rustic. Nicer than the residence houses. But the doors are alarmed and they have guards and stuff.”

“Well, I mean—” I thought of Dorit Villiers—frizzy gold hair; blank blue eyes like a loopy Christmas tree angel—and didn’t know what to say.

“That’s only where they put the really crazy girls. La Grange. I’m in Bessonet, with a bunch of French-speaking girls. It’s supposed to be so I learn French better but all it means is nobody talks to me.”

“You should tell her you don’t like it! Your aunt.”

She grimaced. “I do. But then she starts telling me how much it costs. Or else says I’m hurting her feelings. Anyway,” she said, uneasily, in an I’ve got to go voice, looking over her shoulder.

“Huh,” I said, at last, after a woozy pause. Day and night, my delirium had been colored with an awareness of her in the house, recurring energy-surges of happiness at the sound of her voice in the hallway, her footsteps: we were going to make a blanket tent, she would be waiting for me at the ice rink, bright hum of excitement at all the things we were going to do when I got better—in fact it seemed we had been doing things, such as stringing necklaces of rainbow-colored candy while the radio played Belle and Sebastian and then, later on, wandering through a non-existent casino arcade in Washington Square.

Hobie, I noticed, was standing discreetly in the hall. “Sorry,” he said, glancing at his wristwatch. “I really hate to rush you—”

“Sure,” she said. To me she said: “Goodbye then. Hope you feel better.”

“Wait!”

“What?” she said, half turning.

“You’ll be back for Christmas, right?”

“Nope, Aunt Margaret’s.”

“When are you coming back, then?”

“Well—” one-shouldered shrug. “Dunno. Spring holidays maybe.”

“Pips—” said Hobie, though he was really speaking to me instead of her.

“Right,” she said, brushing her hair from her eyes.

I waited until I heard the front door shut. Then I got out of bed and pulled aside the curtain. Through the dusty glass, I watched them going together down the front steps, Pippa in her pink scarf and hat hurrying slightly alongside Hobie’s large, well-dressed form.

For a while after they turned the corner, I stood at the window looking out at the empty street. Then, feeling light-headed and forlorn, I trudged to her bedroom and—unable to resist—cracked the door a sliver.

It was the same as two years before, except emptier. Wizard of Oz and Save Tibet posters. No wheelchair. Window piled with white pebbles of sleet on the sill. But it smelled like her, it was still warm and alive with her presence, and as I stood breathing in her atmosphere I felt a huge happy smile on my face just to be standing there with her fairy tale books, her perfume bottles, her sparkly tray of barrettes and her valentine collection: paper lace, cupids and columbines, Edwardian suitors with rose bouquets pressed to their hearts. Quietly, tiptoeing even though I was barefoot, I walked over to the silver-framed photographs on the dresser—Welty and Cosmo, Welty and Pippa, Pippa and her mother (same hair, same eyes) with a younger and thinner Hobie—

Low buzzing noise, inside the room. Guiltily I turned—someone coming? No: only Popchik, cotton white after his bath, nestled amongst the pillows of her unmade bed and snoring with a drooling, blissful, half-purring sound. And though there was something pathetic about it—taking comfort in her left-behind things like a puppy snuggled in an old coat—I crawled in under the sheets and nestled down beside him, smiling foolishly at the smell of her comforter and the silky feel of it on my cheek.

vi.

“WELL WELL,” SAID Mr. Bracegirdle as he shook Hobie’s hand and then mine. “Theodore—I do have to say—you’re growing up to look a great deal like your mother. I wish she could see you now.”

I tried to meet his eye and not seem embarrassed. The truth was: though I had my mother’s straight hair, and something of her light-and-dark coloring, I looked a whole lot more like my father, a likeness so strong that no chatty bystander, no waitress in any coffee shop had allowed it to pass unremarked—not that I’d ever been happy about it, resembling the parent I couldn’t stand, but to see a younger version of his sulky, drunk-driving face in the mirror was particularly upsetting now that he was dead.

Hobie and Mr. Bracegirdle were chatting in a subdued way—Mr. Bracegirdle was telling Hobie how he’d met my mother, dawning remembrance from Hobie: “Yes! I remember—a foot in less than an hour! My God, I came out of my auction and nothing was moving, I was uptown at the old Parke-Bernet—”

“On Madison across from the Carlyle?”

“Yes—quite a long hoof home.”

“You deal antiques? Down in the Village, Theo says?”

Politely, I sat and listened to their conversation: friends in common, gallery owners and art collectors, the Rakers and the Rehnbergs, the Fawcetts and the Vogels and the Mildebergers and Depews, on to vanished New York landmarks, the closing of Lutèce, La Caravelle, Café des Artistes, what would your mother have thought, Theodore, she loved Café des Artistes. (How did he know that? I wondered.) While I didn’t for an instant believe some of the things my dad, in moments of meanness, had insinuated about my mother, it did appear that Mr. Bracegirdle had known my mother a good deal better than I would have thought. Even the non-legal books on his shelf seemed to suggest a correspondence, an echo of interests between them. Art books: Agnes Martin, Edwin Dickinson. Poetry too, first editions: Ted Berrigan. Frank O’Hara, Meditations in an Emergency. I remembered the day she’d turned up flushed and happy with the exact same edition of Frank O’Hara—which I assumed she’d found at the Strand, since we didn’t have the money for something like that. But when I thought about it, I realized she hadn’t told me where she’d got it.

“Well, Theodore,” said Mr. Bracegirdle, calling me back to myself. Though elderly, he had the calm, well-tanned look of someone who spent a lot of his spare time on the tennis court; the dark pouches under his eyes gave him a genial panda-bear aspect. “You’re old enough that a judge would consider your wishes above all in this matter,” he was saying. “Especially since your guardianship would be uncontested—of course,” he said to Hobie, “we could seek a temporary guardianship for the upcoming interlude, but I don’t think that will be necessary. Clearly this arrangement is in the minor’s best interests, as long as it’s all right with you?”

“That and more,” said Hobie. “I’m happy if he’s happy.”

“You’re fully prepared to act in an informal capacity as Theodore’s adult custodian for the time being?”

“Informal, black tie, whatever’s called for.”

“There’s your schooling to look after as well. We’d spoken of boarding school, as I recall. But that seems a lot to think of now, doesn’t it?” he said, noting the stricken look on my face. “Shipping out as you’ve just arrived, and with the holidays coming up? No need to make any decisions at all at the moment, I shouldn’t think,” he said, with a glance at Hobie. “I should think it would be fine if you just sat out the rest of this term and we can sort it out later. And you know that you can of course call upon me at any time. Day or night.” He was writing a phone number on a business card. “This is my home number, and this is my cell—my, my, that’s a nasty cough you have there!” he said, glancing up—“quite a cough, are you having that looked after, yes? and this is my number out in Bridgehampton. I hope you won’t hesitate to call me for any reason, if you need anything.”

Trying hard, doing my best, to swallow another cough. “Thank you—”

“This is definitely what you want?” He was looking at me keenly with an expression that made me feel like I was on the witness stand. “To be at Mr. Hobart’s for the next few weeks?”

I didn’t like the sound of the next few weeks. “Yes,” I said into my fist, “but—”

“Because—boarding school.” He folded his hands and leaned back in his chair and regarded me. “Almost certainly the best thing for you in the long term but quite frankly, given the situation, I believe I could telephone my friend Sam Ungerer at Buckfield and we could get you up there right now. Something could be arranged. It’s an excellent school. And I think it would be possible to arrange for you to stay in the home of the headmaster or one of the teachers rather than the dormitory, so you could be in more of a family setting, if you thought that would be something you’d like.”

He and Hobie were both looking at me, encouragingly as I thought. I stared at my shoes, not wanting to seem ungrateful but wishing that this line of suggestion would go away.

“Well.” Mr. Bracegirdle and Hobie exchanged a glance—was I wrong to see a hint of resignation and/or disappointment in Hobie’s expression? “As long as this is what you want, and Mr. Hobart’s amenable, I see nothing wrong with this arrangement for the time being. But I do urge you to think about where you’d like to be, Theodore, so we can go ahead and work out something for the next school term or maybe even summer school, if you’d like.”

vii.

TEMPORARY GUARDIANSHIP. IN THE next weeks, I did my best to buckle down and not think too much about what temporary might mean. I’d applied to an early-college program in the city—my reasoning being that it would keep me from being shipped out to the sticks if for some reason things at Hobie’s didn’t work. All day in my room, under a weak lamp, as Popchik snoozed on the carpet by my feet, I spent hunched over test preparation booklets, memorizing dates, proofs, theorems, Latin vocabulary words, so many irregular verbs in Spanish that even in my dreams I looked down the lines of long tables and despaired of keeping them straight.

It was as if I was trying to punish myself—maybe even make things up to my mother—by setting my sights so high. I’d fallen out of the habit of doing schoolwork; it wasn’t exactly as if I’d kept up my studies in Vegas and the sheer amount of material to memorize gave me a feeling of torture, lights turned in the face, not knowing the correct answer, catastrophe if I failed. Rubbing my eyes, trying to keep myself awake with cold showers and iced coffee, I goaded myself on by reminding myself what a good thing I was doing, though my endless cramming felt a lot more like self destruction than any glue-sniffing I’d ever done; and at some bleary point, the work itself became a kind of drug that left me so drained that I could hardly take in my surroundings.

And yet I was grateful for the work because it kept me too mentally bludgeoned to think. The shame that tormented me was all the more corrosive for having no very clear origin: I didn’t know why I felt so tainted, and worthless, and wrong—only that I did, and whenever I looked up from my books I was swamped by slimy waters rushing in from all sides.

Part of it had to do with the painting. I knew nothing good would come of keeping it, and yet I also knew I’d kept it too long to speak up. Confiding in Mr. Bracegirdle was foolhardy. My position was too precarious; he was already champing at the bit to send me to boarding school. And when I thought, as I often did, of confiding in Hobie, I found myself drifting into various theoretical scenarios none of which seemed any more or less probable than the others.

I would give the painting to Hobie and he would say, ‘oh, no big deal’ and somehow (I had problems with this part, the logistics of it) he would take care of it, or phone some people he knew, or have a great idea about what to do, or something, and not care, or be mad, and somehow it would all be fine?

Or: I would give the painting to Hobie and he would call the police.

Or: I would give the painting to Hobie and he would take the painting for himself and then say, ‘what, are you crazy? Painting? I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

Or: I would give the painting to Hobie and he would nod and look sympathetic and tell me I’d done the right thing but then as soon as I was out of the room he would phone his own lawyer and I would be dispatched to boarding school or a juvenile home (which, painting or not, was where most of my scenarios ended up anyway).

But by far the greater part of unease had to do with my father. I knew that his death wasn’t my fault, and yet on a bone-deep, irrational, completely unshakable level I also knew that it was. Given how coldly I’d walked away from him in his final despair, the fact that he’d lied was beside the point. Maybe he’d known that it was in my power to pay his debt—a fact which had haunted me since Mr. Bracegirdle had so lightly let it slip. In the shadows beyond the desk lamp, Hobie’s terra-cotta griffins stared at me with beady glass eyes. Did he think I’d stiffed him on purpose? That I wanted him to die? At night, I dreamed of him beaten and chased through casino parking lots, and more than once awoke with a jolt to him sitting in the chair by my bed and observing me quietly, the coal of his cigarette glowing in the dark. But they told me you died, I said aloud, before realizing he wasn’t there.

Without Pippa, the house was deathly quiet. The closed-off formal rooms smelled faint and damp, like dead leaves. I mooned about looking at her things, wondering where she was and what she was doing and trying hard to feel connected to her by such tenuous threads as a red hair in the bathtub drain or a balled-up sock under the sofa. But as much as I missed the nervous tingle of her presence, I was soothed by the house, its sense of safety and enclosure: old portraits and poorly lit hallways, loudly ticking clocks. It was as if I’d signed on as a cabin boy on the Marie Céleste. As I moved about through the stagnant silences, the pools of shadow and deep sun, the old floors creaked underfoot like the deck of a ship, the wash of traffic out on Sixth Avenue breaking just audibly against the ear. Upstairs, puzzling light-headed over differential equations, Newton’s Law of Cooling, independent variables, we have used the fact that tau is constant to eliminate its derivative, Hobie’s presence below stairs was an anchor, a friendly weight: I was comforted to hear the tap of his mallet floating up from below and to know that he was down there pottering quietly with his tools and his spirit gums and varicolored woods.

With the Barbours, my lack of pocket money had been a continual worry; having always to hit Mrs. Barbour up for lunch money, lab fees at school, and other small expenses had occasioned dread and anxiety quite out of proportion to the sums she carelessly disbursed. But my living stipend from Mr. Bracegirdle made me feel a lot less awkward about throwing myself down in Hobie’s household, unannounced. I was able to pay Popchik’s vet bills, a small fortune, since he had bad teeth and a mild case of heartworm—Xandra to my knowledge never having given him a pill or taken him for shots my whole time in Vegas. I was also able to pay my own dentist bills, which were considerable (six fillings, ten hellish hours in the dentist’s chair) and buy myself a laptop and an iPhone, as well as the shoes and winter clothes I needed. And—though Hobie wouldn’t accept grocery money—still I went out and got groceries for him all the same, groceries I paid for: milk and sugar and washing powder from Grand Union, but more often fresh produce from the farmers’ market at Union Square, wild mushrooms and winesap apples, raisin bread, small luxuries which seemed to please him, unlike the large containers of Tide which he looked at sadly and took to the pantry without a word.

It was all very different from the crowded, complicated, and overly formal atmosphere of the Barbours’, where everything was rehearsed and scheduled like a Broadway production, an airless perfection from which Andy had been in constant retreat, scuttling to his bedroom like a frightened squid. By contrast Hobie lived and wafted like some great sea mammal in his own mild atmosphere, the dark brown of tea stains and tobacco, where every clock in the house said something different and time didn’t actually correspond to the standard measure but instead meandered along at its own sedate tick-tock, obeying the pace of his antique-crowded backwater, far from the factory-built, epoxy-glued version of the world. Though he enjoyed going out to the movies, there was no television; he read old novels with marbled end papers; he didn’t own a cell phone; his computer, a prehistoric IBM, was the size of a suitcase and useless. In blameless quiet, he buried himself in his work, steam-bending veneers or hand-threading table legs with a chisel, and his happy absorption floated up from the workshop and diffused through the house with the warmth of a wood-burning stove in winter. He was absent-minded and kind; he was neglectful and muddle-headed and self-deprecating and gentle; often he didn’t hear the first time you spoke to him, or even the second time; he lost his glasses, mislaid his wallet, his keys, his dry-cleaning tickets, and was always calling me downstairs to get on my hands and knees with him to help him search for some minuscule fitting or piece of hardware he’d dropped on the floor. Occasionally he opened the store by appointment, for an hour or two at a time, but—as far as I could tell—this was little more than an excuse to bring out the bottle of sherry and visit with friends and acquaintances; and if he showed a piece of furniture, opening and shutting drawers to oohs and aahs, it seemed to be mostly in the spirit in which Andy and I, once upon a time, had dragged out our toys for show and tell.

If he ever actually sold a piece, I never saw him do it. His bailiwick (as he called it) was the workshop, or the ‘hospital’ rather, where the crippled chairs and tables stood stacked awaiting his care. Like a gardener occupied with greenhouse specimens, brushing aphids from individual plant leaves, he absorbed himself in the texture and grain of individual pieces, the hidden drawers, the scars and marvels. Though he owned a few items of modern woodworking equipment—a router, a cordless drill and a circular saw—he seldom used them. (“If it requires earplugs, I haven’t much call for it.”) He went down there early and sometimes, if he had a project, stayed down there after dark, but generally when the light started to go he came upstairs and—before washing up for dinner—poured himself the same inch of whiskey, neat, in a small tumbler: tired, congenial, lamp-black on his hands, something rough and soldierly in his fatigue. Has he takn u out to dinner, Pippa texted me.

Yes like 3 or 4x

He only likes 2go 2 3mpty rstrnts where nobody goes.

Thats right the place he took me last week was like king tuts tomb

Yes he only goes places where he feels sorry for the owners! because he is scared they will go out of business and then he will feel guilty

I like it better when he cooks

Ask him to make gingerbread for u I wish i had some now

Dinner was the time of day I looked forward to most. In Vegas—especially after Boris had taken up with Kotku—I’d never gotten used to the sadness of having to scrabble around to feed myself at night, sitting on the side of my bed with a bag of potato chips or maybe a dried-up container of rice left over from my dad’s carry out. By happy contrast, Hobie’s whole day revolved around dinner. Where shall we eat? Who’s coming over? What shall I cook? Do you like pot-au-feu? No? Never had it? Lemon rice or saffron? Fig preserves or apricot? Do you want to walk over to Jefferson Market with me? Sometimes on Sundays there were guests, who among New School and Columbia professors, opera-orchestra and preservation-society ladies, and various old dears from up and down the street also included a great many dealers and collectors of all stripes, from batty old ladies in fingerless gloves who sold Georgian jewelry at the flea market to rich people who wouldn’t have been out of place at the Barbours (Welty, I learned, had helped many of these people build their collections, by advising them what pieces to buy). Most of the conversation left me wholly at sea (St-Simon? Munich Opera Festival? Coomaraswamy? The villa at Pau?). But even when the rooms were formal and the company was “smart” his lunches were the sort where people didn’t seem to mind serving themselves or eating from plates in their laps, as opposed to the rigidly catered parties always tinkling frostily away at the Barbours’ house.

In fact, at these dinners, as agreeable and interesting as Hobie’s guests were, I constantly worried that somebody who knew me from the Barbours was going to turn up. I felt guilty for not calling Andy; and yet, after what had happened with his dad on the street, I felt even more ashamed for him to know that I’d washed up in the city again with no place of my own to live.

And—though it was a small matter enough—I was still bothered by how I’d turned up at Hobie’s in the first place. Though he never told the story in front of me, how I’d showed up on the doorstep, mainly because he could see how uncomfortable it made me, still he’d told people—not that I blamed him; it was too good a story not to tell. “It’s so fitting if you knew Welty,” said Hobie’s great friend Mrs. DeFrees, a dealer in nineteenth-century watercolors who for all her stiff clothes and strong perfumes was a hugger and a cuddler, with the old-ladyish habit of liking to hold your arm or pat your hand as she talked. “Because, my dear, Welty was an agoramaniac. Loved people, you know, loved the marketplace. The to and the fro of it. Deals, goods, conversation, exchange. It was that eeny bit of Cairo from his boyhood, I always said he would have been perfectly happy padding around in slippers and showing carpets in the souk. He had the antiquaire’s gift, you know—he knew what belonged with whom. Someone would come in the shop never intending to buy a thing, ducking in out of the rain maybe, and he’d offer them a cup of tea and they’d end up having a dining room table shipped to Des Moines. Or a student would wander in to admire, and he’d bring out just the little inexpensive print. Everyone was happy, do you know. He knew everybody wasn’t in the position to come in and buy some big important piece—it was all about matchmaking, finding the right home.”

“Well, and people trusted him,” said Hobie, coming in with Mrs. DeFrees’s thimble of sherry and a glass of whiskey for himself. “He always said his handicap was what made him a good salesman and I think there’s something to that. ‘The sympathetic cripple.’ No axe to grind. Always on the outside, looking in.”

“Ah, Welty was never on the outside of anything,” said Mrs. DeFrees, accepting her glass of sherry and patting Hobie affectionately on the sleeve, her little paper-skinned hand glittering with rose-cut diamonds. “He was always right in the thick of it, bless him, laughing that laugh, never a word of complaint. Anyway, my dear,” she said, turning back to me, “make no mistake about it. Welty knew exactly what he was doing by giving you that ring. Because by giving it to you, he brought you straight here to Hobie, you see?”

“Right,” I said—and then I’d had to get up and walk in the kitchen, so troubled was I by this detail. Because, of course, it wasn’t just the ring he had given me.

viii.

AT NIGHT, IN WELTY’S old room, which was now my room, his old reading glasses and fountain pens still in the desk drawers, I lay awake listening to the street noise and fretting. It had crossed my mind in Vegas that if my dad or Xandra found the painting they might not know what it was, at least not right away. But Hobie would know. Over and over I found myself envisioning scenarios where I came home to discover Hobie waiting for me with the painting in his hands—“what’s this?”—for there was no flim-flam, no excuse, no pre-emptive line with which to meet such a catastrophe; and when I got on my knees and reached under the bed to put my hands on the pillowcase (as I did, blindly and at erratic interludes, to make sure it was still there) it was a quick feint and drop like grabbing at a too-hot microwave dinner.

A house fire. An exterminator visit. Big red INTERPOL on the Missing Art Database. If anyone cared to make the connection, Welty’s ring was proof positive that I’d been in the gallery with the painting. The door to my room was so old and uneven on its hinges that it didn’t even catch properly; I had to prop it shut with an iron doorstop. What if, driven by some unanticipated impulse, he took it in his head to come upstairs and clean? Admittedly this seemed out of character for the absent-minded and not-particularly-tidy Hobie I knew—No he dosn’t care if U R messy he never goes in my room except to change sheets & dust Pippa had texted, prompting me to strip my bed immediately and spend forty-five frantic minutes dusting every surface in my room—the griffons, the crystal ball, the headboard of the bed—with a clean T-shirt. Dusting soon became an obsessive habit—enough that I went out and bought my own dust cloths, even though Hobie had a house full of them; I didn’t want him to see me dusting, my only hope was that the word dust would never occur to him if he happened to poke his head in my room.

For this reason, because I was really only comfortable leaving the house in his company, I spent most of my days in my room, at my desk, with scarcely a break for meals. And when he went out, I tagged along with him to galleries, estate sales, showrooms, auctions where I stood with him in the very back (“no, no,” he said, when I pointed out the empty chairs in front, “we want to be where we can see the paddles”)—exciting at first, just like the movies, though after a couple of hours as tedious as anything in Calculus: Concepts and Connections.

But though I tried (with some success) to act blasé, trailing him indifferently around Manhattan as if I didn’t care one way or another, in truth I stuck to him in much the same anxious spirit that Popchik—desperately lonely—had followed along constantly behind Boris and me in Vegas. I went with him to snooty lunches. I went with him on appraisals. I went with him to his tailor. I went with him to poorly attended lectures on obscure Philadelphia cabinet-makers of the 1770s. I went with him to the Opera Orchestra, even though the programs were so boring and dragged on so long that I feared I might actually black out and topple into the aisle. I went with him to dinner with the Amstisses (on Park Avenue, uncomfortably close to the Barbours’) and the Vogels, and the Krasnows, and the Mildebergers, where the conversation was either a.) so eye-crossingly dull or b.) so far over my head that I could never manage much more than hmn. (“Poor boy, we must be hopelessly uninteresting to you,” said Mrs. Mildeberger brightly, not appearing to realize how truly she spoke.) Other friends, like Mr. Abernathy—my dad’s age, with some ill-articulated scandal or disgrace in his past—were so mercurial and articulate, so utterly dismissive of me (“And where did you say you obtained this child, James?”) that I sat dumbfounded among the Chinese antiquities and Greek vases, wanting to say something clever while at the same time terrified of attracting attention in any way, feeling tongue-tied and completely at sea. At least once or twice a week we went to Mrs. DeFrees in her antique-packed townhouse (the uptown analogue of Hobie’s) on East Sixty-Third, where I sat on the edge of a spindly chair and tried to ignore her frightening Bengal cats digging their claws in my knees. (“He’s a socially alert little creature, isn’t he?” I heard her remark not so sotto voce when they were across the room fussing over some Edward Lear watercolors.) Sometimes she accompanied us to the showings at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, Hobie poring over every piece, opening and shutting drawers, showing me various points of workmanship, marking up his catalogue with a pencil—and then, after a stop or two at a gallery along the way, she went back to Sixty-Third Street and we went to Sant Ambrœus, where Hobie, in his smart suit, stood at the counter and drank an espresso while I ate a chocolate croissant and looked at the kids with book bags coming in and hoped I didn’t see anyone I knew from my old school.

“Would your dad like another espresso?” the counterman asked when Hobie excused himself to go to the gents’.

“No thanks, I think just the check.” It thrilled me, deplorably, when people mistook Hobie for my parent. Though he was old enough to be my grandfather, he projected a vigor more in keeping with older European dads you saw on the East Side—polished, portly, self-possessed dads on their second marriages who’d had kids at fifty and sixty. In his gallery-going clothes, sipping his espresso and looking out peacefully at the street, he might have been a Swiss industrial magnate or a restaurateur with a Michelin star or two: substantial, late-married, prosperous. Why, I thought sadly, as he returned with his topcoat over his arm, why hadn’t my mother married someone like him—? Or Mr. Bracegirdle? somebody she actually had something in common with—older maybe but personable, someone who enjoyed galleries and string quartets and poking around used book stores, someone attentive, cultivated, kind? Who would have appreciated her, and bought her pretty clothes and taken her to Paris for her birthday, and given her the life she deserved? It wouldn’t have been hard for her to find someone like that, if she’d tried. Men had loved her: from the doormen to my schoolteachers to the fathers of my friends right on up to her boss Sergio at work (who had called her, for reasons unknown to me, Dollybird), and even Mr. Barbour had always been quick to jump up and greet her when she came to pick me up from sleepovers, quick with the smiles and quick to touch her elbow as he steered her to the sofa, voice low and companionable, won’t you sit down? would you like a drink, a cup of tea, anything? I did not think it was my imagination—not quite—how closely Mr. Bracegirdle had looked at me: almost as if he were looking at her, or looking for some trace of her ghost in me. Yet even in death my dad was ineradicable, no matter how hard I tried to wish him out of the picture—for there he always was, in my hands and my voice and my walk, in my darting sideways glance as I left the restaurant with Hobie, the very set of my head recalling his old, preening habit of checking himself out in any mirror-like surface.

ix.

IN JANUARY, I HAD my tests: the easy one and the hard one. The easy one was in a high school classroom in the Bronx: pregnant moms, assorted cabdrivers, and a raucous gaggle of Grand Concourse homegirls with short fur jackets and sparkle fingernails. But the test was not actually so easy as I thought it would be, with a lot more questions about arcane matters of New York State government than I’d anticipated (how many months of the year was the legislature in Albany in session? How the hell was I supposed to know?), and I came home on the subway preoccupied and depressed. And the hard test (locked classroom, uptight parents pacing the hallways, the strained atmosphere of a chess tournament) seemed to have been designed with some twitching, MIT-bred recluse in mind, with many of the multiple-choice answers so similar that I came away with literally no idea how I’d done.

So what, I told myself, walking up to Canal Street to catch the train with my hands shoved deep in my pockets and my armpits rank with anxious classroom perspiration. Maybe I wouldn’t get into the early-college program—and what if I didn’t? I had to do well, very well, in the top thirty per cent, if I stood any chance at all.

Hubris: a vocabulary word that had featured prominently on my pre-tests though it hadn’t shown up on the tests proper. I was competing with five thousand applicants for something like three hundred places—if I didn’t make the cut, I wasn’t sure what would happen; I didn’t think I could bear it if I had to go to Massachusetts and stay with these Ungerer people Mr. Bracegirdle kept talking about, this good-guy headmaster and his “crew,” as Mr. Bracegirdle called them, mom and three boys, whom I imagined as a slab-like, stair-stepped, whitely smiling line of the same prep-school hoods who with cheerful punctuality in the bad old days had beaten up Andy and me and made us eat dust balls off the floor. But if I failed the test (or, more accurately, didn’t do quite well enough to make the early-college program), how would I be able to work things so I could stay in New York? Certainly I should have aimed for a more achievable goal, some decent high school in the city where I would have at least had a chance of getting in. Yet Mr. Bracegirdle had been so adamant about boarding school, about fresh air and autumn color and starry skies and the many joys of country life (“Stuyvesant. Why would you stay here and go to Stuyvesant when you could get out of New York? Stretch your legs, breathe a bit easier? Be in a family situation?”) that I’d stayed away from high schools altogether, even the very best ones.

“I know what your mother would have wanted for you, Theodore,” he’d said repeatedly. “She would have wanted a fresh start for you. Out of the city.” He was right. But how could I explain to him, in the chain of disorder and senselessness that had followed her death, exactly how irrelevant those old wishes were?

Still lost in thought as I turned the corner to the station, fishing in my pocket for my MetroCard, I passed a newsstand where I saw a headline reading:

MUSEUM MASTERWORKS RECOVERED IN BRONX MILLIONS IN STOLEN ART

I stopped on the sidewalk, commuters streaming past me on either side. Then—stiffly, feeling observed, heart pounding—I walked back and bought a copy (certainly buying a newspaper was a less suspicious thing for a kid my age to do than it seemed to be—?) and ran across the street to the benches on Sixth Avenue to read it.

Police, acting on a tip, had recovered three paintings—a George van der Mijn; a Wybrand Hendriks; and a Rembrandt, all missing from the museum since the explosion—from a Bronx home. The paintings had been found in an attic storage area, wrapped in tinfoil and stacked amidst a bunch of spare filters for the building’s central air-conditioning unit. The thief, his brother, and the brother’s mother-in-law—owner of the premises—were in custody pending bail; if convicted on all charges, they faced combined sentences of up to twenty years.

It was a pages-long article, complete with timelines and diagram. The thief—a paramedic—had lingered after the call to evacuate, removed the paintings from the wall, draped them with a sheet, concealed them beneath a folded-up portable stretcher, and walked with them from the museum unobserved. “Chosen with no eye to value,” said the FBI investigator interviewed for the article. “Snatch and grab. The guy didn’t know a thing about art. Once he got the paintings home he didn’t know what to do with them so he consulted with his brother and together they hid the works at the mother-in-law’s, without her knowledge according to her.” After a little Internet research, the brothers had apparently realized that the Rembrandt was too famous to sell, and it was their efforts to sell one of the lesser-known works that led investigators to the cache in the attic.

But the final paragraph of the article leaped out as if it had been printed in red.

As for other art still missing, the hopes of investigators have been revived, and authorities are now looking into several local leads. “The more you shake the trees, the more falls out of them,” said Richard Nunnally, city police liaison with the FBI art crimes unit. “Generally, with art theft, the pattern is for pieces to be whisked out of the country very quickly, but this find in the Bronx only goes to confirm that we probably have quite a few amateurs at work, inexperienced parties who stole on impulse and don’t have the know-how to sell or conceal these objects.” According to Nunnally, a number of people present at the scene are being questioned, contacted, and reinvestigated: “Obviously, now, the thinking is that a lot of these missing pictures may be here in the city right under our noses.”

I felt sick. I got up and dumped the paper in the nearest trash can, and—instead of getting on the subway—wandered back down Canal Street and roamed around Chinatown for an hour in the freezing cold, cheap electronics and blood red carpets in the dim sum parlors, staring in fogged windows at mahogany racks of rotisseried Peking duck and thinking: shit, shit. Red-cheeked street vendors, bundled like Mongolians, shouting above smoky braziers. District Attorney. FBI. New information. We are determined to prosecute these cases to the fullest extent of the law. We have full confidence that other missing works will surface soon. Interpol, UNESCO and other federal and international agencies are cooperating with local authorities in the case.

It was everywhere. All the newspapers had it: even the Mandarin newspapers, the recovered Rembrandt portrait amid streams of Chinese print, peeping out from bins of unidentifiable vegetables and eels on ice.

“Really disturbing,” said Hobie later that night at dinner with the Amstisses, brow knitted with anxiety. The recovered paintings were all he’d been able to talk about. “Wounded people everywhere, people bleeding to death, and here’s this fellow snatching paintings off the walls. Carrying them around outside in the rain.”

“Well, can’t say I’m surprised,” said Mr. Amstiss, who was on his fourth scotch on the rocks. “After that second heart attack of Mother’s? You can’t believe the mess these goons from Beth Israel left. Black footprints all over the carpet. We were finding plastic needle caps all over the floor for weeks, the dog almost swallowed one. And they broke something too, Martha, something in the china cabinet, what was it?”

“Listen, you won’t catch me complaining about paramedics,” said Hobie. “I was really impressed with the ones we had when Juliet was ill. I’m just glad they found the paintings before they were too badly damaged, it could have been a real—Theo?” he said to me, rather suddenly, causing me to glance up quickly from my plate. “Everything all right?”

“Sorry. I’m just tired.”

“No wonder,” said Mrs. Amstiss kindly. She taught American history at Columbia; she, of the pair, was the one Hobie liked and was friends with, Mr. Amstiss being the unfortunate half of the package. “You’ve had a tough day. Worried about your test?”

“No, not really, “ I said without thinking, and then was sorry.

“Oh, I’m sure he’ll get in,” said Mr. Amstiss. “You’ll get in,” he said to me, in a tone implying that any idiot could expect to do so, and then, turning back to Hobie: “Most of these early-college programs don’t deserve the name, isn’t that right, Martha? Glorified high school. Tough pull to get in but then a doddle once you’ve made it. That’s the way it is these days with the kids—participate, show up, and they expect a prize. Everybody wins. Do you know what one of Martha’s students said to her the other day? Tell them, Martha. This kid comes up after class, wants to talk. Shouldn’t say kid—graduate student. And you know what he says?”

“Harold,” said Mrs. Amstiss.

“Says he’s worried about his test performance, wants her advice. Because he has a hard time remembering things. Does that take the cake, or what? Graduate student in American history? Hard time remembering things?”

“Well, God knows, I have a hard time remembering things too,” said Hobie affably, and rising with the dishes, steered the conversation into other channels.

But late that night, after the Amstisses had left and Hobie was asleep, I sat up in my room staring out the window at the street, listening to the distant two a.m. grindings of trucks over on Sixth Avenue and doing my best to talk myself down from my panic.

Yet what could I do? I’d spent hours on my laptop, clicking rapidly through what seemed like hundreds of articles—Le Monde, Daily Telegraph, Times of India, La Repubblica, languages I couldn’t read, every paper in the world was covering it. The fines, in addition to the prison sentences, were ruinous: two hundred thousand, half a million dollars. Worse: the woman who owned the house was being charged because the paintings had been found on her property. And what this meant, very likely, was that Hobie would be in trouble too—much worse trouble than me. The woman, a retired beautician, claimed she’d had no idea the paintings were in her house. But Hobie? An antiques dealer? Never mind that he’d taken me in innocently, out of the goodness of his heart. Who would believe he hadn’t known about it?

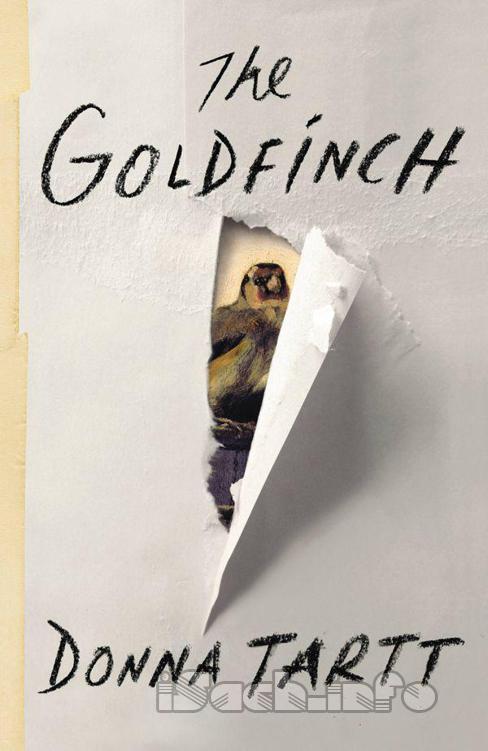

Up, down and around my thoughts plunged, like a bad carnival ride. Though these thieves acted impulsively and have no prior criminal records, their inexperience will not deter us from prosecuting this case to the letter of the law. One commentator, in London, had mentioned my painting in the same breath with the recovered Rembrandt:… has drawn attention to more valuable works still missing, most particularly Carel Fabritius’s Goldfinch of 1654, unique in the annals of art and therefore priceless…

I reset the computer for the third or fourth time and shut it down, and then, a bit stiffly, climbed in bed and turned out the light. I still had the baggie of pills I’d stolen from Xandra—hundreds of them, all different colors and sizes, all painkillers according to Boris, but though sometimes they knocked my dad out cold I’d also heard him complaining how sometimes they kept him awake at night, so—after lying paralyzed with discomfort and indecision for an hour or more, seasick and tossing, staring at the spokes of car lights wheeling across the ceiling—I snapped on the light again and scrabbled around in the nightstand drawer for the bag and selected two different colored pills, a blue and a yellow, my reasoning being that if one didn’t put me to sleep, the other might.

Priceless. I rolled to face the wall. The recovered Rembrandt had been valued at forty million. But forty million was still a price.

Out on the avenue, a fire engine screamed high and hard before trailing into the distance. Cars, trucks, loudly-laughing couples coming out of the bars. As I lay awake trying to think of calming things like snow, and stars in the desert, hoping I hadn’t swallowed the wrong mix and accidentally killed myself, I did my best to hold tight to the one helpful or comforting fact I’d gleaned from my online reading: stolen paintings were almost impossible to trace unless people tried to sell them, or move them, which was why only twenty per cent of art thieves were ever caught.

ePub

ePub A4

A4