Chapter 6

O

VER THE NEXT YEAR, I was so preoccupied in trying to block New York and my old life out of my mind that I hardly noticed the time pass. Days ran changelessly in the seasonless glare: hungover mornings on the school bus and our backs raw and pink from falling asleep by the pool, the gasoline reek of vodka and Popper’s constant smell of wet dog and chlorine, Boris teaching me to count, ask directions, offer a drink in Russian, just as patiently as he’d taught me to swear. Yes, please, I’d like that. Thank you, you are very kind. Govorite li vy po angliyskiy? Do you speak English? Ya nemnogo govoryu po-russki. I do speak Russian, a little.Winter or summer, the days were dazzling; the desert air burned our nostrils and scraped our throats dry. Everything was funny; everything made us laugh. Sometimes, just before sundown, just as the blue of the sky began darkening to violet, we had these wild, electric-lined, Maxfield Parrish clouds rolling out gold and white into the desert like Divine Revelation leading the Mormons west. Govorite medlenno, I said, speak slowly, and Povtorite, pozhaluysta. Repeat, please. But we were so attuned to each other that we didn’t need to talk at all if we didn’t want to; we knew how to tip each other over in hysterics with an arch of the eyebrow or quirk of the mouth. Nights, we ate crosslegged on the floor, leaving greasy fingerprints on our schoolbooks. Our diet had made us malnourished, with soft brown bruises on our arms and legs—vitamin deficiency, said the nurse at school, who gave us each a painful shot in the ass and a colorful jar of children’s chewables. (“My bottom hurts,” said Boris, rubbing his rear end and cursing the metal seats on the school bus.) I was freckled head to toe from all the swimming we did; my hair (longer then than it’s ever been again) got light streaks from the pool chemicals and basically I felt good, though I still had a heaviness in my chest that never went away and my teeth were rotting out in the back from all the candy we ate. Apart from that, I was fine. And so the time passed happily enough; but then—shortly after my fifteenth birthday—Boris met a girl named Kotku; and everything changed.

The name Kotku (Ukrainian variant: Kotyku) makes her sound more interesting than she was; but it wasn’t her real name, only a pet name (“Kitty cat,” in Polish) that Boris had given her. Her last name was Hutchins; her given name was actually something like Kylie or Keiley or Kaylee; and she’d lived in Clark County, Nevada her whole life. Though she went to our school and was only a grade ahead of us, she was a lot older—older than me by three whole years. Boris, apparently, had had his eye on her for a while, but I hadn’t been aware of her until the afternoon he threw himself on the foot of my bed and said: “I’m in love.”

“Oh yeah? With who?”

“This chick from Civics. That I bought some weed from. I mean, she’s eighteen, too, can you believe it? God, she’s beautiful.”

“You have weed?”

Playfully, he lunged and caught me by the shoulder; he knew just where I was weakest, the spot under the blade where he could dig his fingers and make me yelp. But I was in no mood and hit him, hard.

“Ow! Fuck!” said Boris, rolling away, rubbing his jaw with his fingertips. “Why’d you do that?”

“Hope it hurts,” I said. “Where’s that weed?”

We didn’t talk any more about Boris’s love interest, at least not that day, but then a few days later when I came out of math I saw him looming over this girl by the lockers. While Boris wasn’t especially tall for his age, the girl was tiny, despite how much older than us she seemed: flat-chested, scrawny-hipped, with high cheekbones and a shiny forehead and a sharp, shiny, triangle-shaped face. Pierced nose. Black tank top. Chipped black fingernail polish; streaked orange-and-black hair; flat, bright, chlorine-blue eyes, outlined hard, in black pencil. Definitely she was cute—hot, even; but the glance she slid over me was anxiety-provoking, something about her of a bitchy fast-food clerk or maybe a mean babysitter.

“So what do you think?” said Boris eagerly when he caught up with me after school.

I shrugged. “She’s cute. I guess.”

“You guess?”

“Well Boris, I mean, she looks like she’s, like, twenty-five.”

“I know! It’s great!” he said, looking dazed. “Eighteen years! Legal adult! She can buy booze no problem! Also she’s lived here her whole life, so she knows what places don’t check age.”

ii.

HADLEY, THE TALKATIVE LETTER-JACKET girl who sat by me in American history, wrinkled her nose when I asked about Boris’s older woman. “Her?” she said. “Total slut.” Hadley’s big sister, Jan, was in the same grade with Kyla or Kayleigh or whatever her name was. “And her mother, I heard, is a straight-up hooker. Your friend better be careful he doesn’t get some disease.”

“Well,” I said, surprised at her vehemence, though maybe I shouldn’t have been. Hadley, an army brat, was on the swim team and sang in the school choir; she had a normal family with three siblings, a Weimaraner named Gretchen that she’d brought over from Germany, and a dad who yelled if she was out past her curfew.

“I’m not kidding,” said Hadley. “She’ll make out with other girls’ boyfriends—she’ll make out with other girls—she’ll make out with anybody. Also I think she does pot.”

“Oh,” I said. None of these factors, in my view, were necessarily reasons to dislike Kylie or whatever, especially since Boris and I had wholeheartedly taken to smoking pot ourselves in the past months. But what did bother me—a lot—was how Kotku (I’ll continue to call her by the name Boris gave her, since I can’t now remember her real name) had stepped in overnight and virtually assumed ownership of Boris.

First he was busy on Friday night. Then it was the whole weekend—not just the night, but the day too. Pretty soon, it was Kotku this and Kotku that, and the next thing I knew, Popper and I were eating dinner and watching movies by ourselves.

“Isn’t she amazing?” Boris asked me again, after the first time he brought her over to my house—a highly unsuccessful evening, which had consisted of the three of us getting so stoned we could barely move, and then the two of them rolling around on the sofa downstairs while I sat on the floor with my back to them and tried to concentrate on a rerun of The Outer Limits. “What do you think?”

“Well, I mean—” What did he want me to say? “She likes you. Sure.”

He shifted, restlessly. We were outside by the pool, though it was too windy and cool to swim. “No, really! What do you think about her? Tell the truth, Potter,” he said, when I hesitated.

“I don’t know,” I said doubtfully, and then—when he still sat looking at me: “Honestly? I don’t know, Boris. She seems kind of desperate.”

“Yes? Is that bad?”

His tone was genuinely curious—not angry, not sarcastic. “Well,” I said, taken aback. “Maybe not.”

Boris—cheeks pink with vodka—put his hand on his heart. “I love her, Potter. I mean it. This is the truest thing that has ever happened to me in my life.”

I was so embarrassed I had to look away.

“Little skinny witch!” He sighed, happily. “In my arms, she’s so bony and light! Like air.” Boris, mysteriously, seemed to adore Kotku for many of the reasons I found her disturbing: her slinky alley-cat body, her scrawny, needy adultness. “And so brave and wise, such a big heart! All I want is to look out for her and keep her safe from that Mike guy. You know?”

Quietly, I poured myself another vodka, though I really didn’t need one. The Kotku business was all doubly perplexing because—as Boris himself had informed me, with an unmistakable note of pride—Kotku already had a boyfriend: a twenty-six-year-old guy named Mike McNatt who owned a motorcycle and worked for a pool cleaning service. “Excellent,” I said, when Boris had broken this news earlier. “We ought to get him out here to help with the vacuuming.” I was sick and tired of looking after the swimming pool (a job that had fallen largely to me), especially since Xandra never brought home enough chemicals or the right kind.

Boris wiped his eyes with the heels of his hands. “It’s serious, Potter. I think she’s scared of him. She wants to break up with him but she’s afraid. She’s trying to talk him into going to a military recruiter.”

“You’d better be careful that guy doesn’t come after you.”

“Me!” He snorted. “It’s her I’m worried about! She’s so tiny! Eighty-one pounds!”

“Yeah, yeah.” Kotku claimed to be a “borderline anorexic” and could always get Boris worked up by saying she hadn’t eaten anything all day.

Boris cuffed me on the side of the head. “You sit too much around here on your own,” he said, sitting down beside me and putting his feet in the pool. “Come to Kotku’s tonight. Bring someone.”

“Such as—?”

Boris shrugged. “What about hot little blondie with the boy’s haircut, from your history class? The swimmer?”

“Hadley?” I shook my head. “No way.”

“Yes! You should! Because she is hot! And she would totally go!”

“Believe me, not a good idea.”

“I’ll ask her for you! Come on. She’s friendly to you, and always talks. Shall we call her?”

“No! It’s not that—stop,” I said, grabbing his sleeve as he started to get up.

“No guts!”

“Boris.” He was heading indoors to the phone. “Don’t. I mean it. She won’t come.”

“And why?”

The taunting edge in his voice annoyed me. “Honestly? Because—” I started to say Because Kotku is a ho which was only the obvious truth but instead I said: “Look, Hadley’s on Honor Roll and stuff. She’s not going to want to go hang out at Kotku’s.”

“What?” said Boris—spinning back, outraged. “That whore. What’d she say?”

“Nothing. It’s just—”

“Yes she did!” He was charging back to the pool now. “You’d better tell me.”

“Come on. It’s nothing. Chill out, Boris,” I said, when I saw how angry he was. “Kotku’s tons older. They’re not even in the same grade.”

“That snub-nosed bitch. What did Kotku ever do to her?”

“Chill out.” My eye landed on the vodka bottle, illumined by a clean white sunbeam like a light saber. He’d had way too much to drink, and the last thing I wanted was a fight. But I was too drunk myself to think of any funny or easy way to get him off the subject.

iii.

LOTS OF OTHER, BETTER girls our own age liked Boris—most notably Saffi Caspersen, who was Danish, spoke English with a high-toned British accent, had a minor role in a Cirque du Soleil production, and was by leaps and bounds the most beautiful girl in our year. Saffi was in Honors English with us (where she’d had some interesting things to say about The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter) and though she had a reputation for being standoffish, she liked Boris. Anyone could see it. She laughed when he made jokes, acted goofy in his study group, and I’d seen her talking enthusiastically to him in the hall—Boris talking back just as enthusiastically, in his gesticulating Russian mode. Yet—mysteriously—he didn’t seem attracted to her at all.

“But why not?” I asked him. “She’s the best-looking girl in our class.” I’d always thought that Danes were large and blonde, but Saffi was smallish and brunette, with a fairy-tale quality that was accentuated by her glittery stage makeup in the professional photo I’d seen.

“Good looking yes. But she is not very hot.”

“Boris, she is smoking hot. Are you crazy?”

“Ah, she works too hard,” said Boris, dropping down beside me with a beer in one hand, reaching for my cigarette with the other. “Too straight. All the time studying or rehearsing or something. Kotku—” he blew out a cloud of smoke, handed the cigarette back to me—“she’s like us.”

I was silent. How had I gone from AP everything to being lumped in with a derelict like Kotku?

Boris nudged me. “I think you like her yourself. Saffi.”

“No, not really.”

“You do. Ask her out.”

“Yeah, maybe,” I said, although I knew I didn’t have the nerve. At my old school, where foreigners and exchange students tended to stand politely at the margins, someone like Saffi might have been more accessible but in Vegas she was much too popular, too surrounded by people—and there was also the biggish problem of what to ask her to do. In New York it would have been easy enough; I could have taken her ice skating, asked her to a movie or the planetarium. But I could scarcely see Saffi Caspersen sniffing glue or drinking beer from paper bags at the playground or doing any of the things that Boris and I did together.

iv.

I STILL SAW HIM—just not as much. More and more he spent nights with Kotku and her mother at the Double R Apartments—a transient hotel really, a broken down motor court from the 1950s, on the highway between the airport and the Strip, where guys who looked like illegal immigrants stood around the courtyard by the empty swimming pool and argued over motorcycle parts. (“Double R?” said Hadley. “You know what that stands for, right? ‘Rats and Roaches.’ ”) Kotku, mercifully, didn’t accompany Boris to my house all that much, but even when she wasn’t around he talked about her constantly. Kotku had cool taste in music and had made him a mix CD with a bunch of smoking hot hip-hop that I really had to listen to. Kotku liked her pizza with green peppers and olives only. Kotku really really wanted an electronic keyboard—also a Siamese kitten, or maybe a ferret, but wasn’t allowed to have pets at the Double R. “Serious, you need to spend more time with her, Potter,” he said, bumping my shoulder with his. “You’ll like her.”

“Oh come on,” I said, thinking of the smirky way she behaved around me—laughing at the wrong time, in a nasty way, always commanding me to go to the fridge to fetch her beers.

“No! She likes you! She does! I mean, she thinks of you more as a little brother. That’s what she said.”

“She never says a word to me.”

“That’s because you don’t talk to her.”

“Are you guys screwing?”

Boris made an impatient noise, the sound he made when things didn’t go his way.

“Dirty mind,” he said, tossing the hair out of his eyes, and then: “What? What do you think? Do you want me to make you a map?”

“Draw you a map.”

“Eh?”

“That’s the phrase. ‘Do you want me to draw you a map.’ ”

Boris rolled his eyes. Waving his hands around, he started in again about how intelligent Kotku was, how “crazy smart,” how wise she was and how much life she had lived and how unfair I was to judge her and look down on her without bothering to get to know her; but while I sat half listening to him talk, and half watching an old noir movie on television (Fallen Angel, Dana Andrews), I couldn’t help thinking about how he’d met Kotku in what was essentially Remedial Civics, the section for students who weren’t smart enough (even in our extremely non-demanding school) to pass without extra help. Boris—good at mathematics without trying and better in languages than anyone I’d ever met—had been forced into Civics for Dummies because he was a foreigner: a school requirement which he greatly resented. (“Because why? Am I likely to be someday voting for Congress?”) But Kotku—eighteen! born and raised in Clark County! American citizen, straight off of Cops!—had no such excuse.

Over and over, I caught myself in mean-spirited thoughts like this, which I did my best to shake. What did I care? Yes, Kotku was a bitch; yes, she was too dumb to pass regular Civics and wore cheap hoop earrings from the drugstore that were always getting caught in things, and yes, even though she was only eighty-one pounds or whatever she still scared the hell out of me, like she might kick me to death with her pointy-toed boots if she got mad enough. (“She a little fighta nigga,” Boris himself had said boastfully at one point as he hopped around throwing out gang signs, or what he thought were gang signs, and regaling me with a story of how Kotku had pulled out a bloody chunk of some girl’s hair—this was another thing about Kotku, she was always getting in scary girl fights, mostly with other white trash girls like herself but occasionally with the real gangsta girls, who were Latina and black.) But who cared what crappy girl Boris liked? Weren’t we still friends? Best friends? Brothers practically?

Then again: there was not exactly a word for Boris and me. Until Kotku came along, I had never thought too much about it. It was just about drowsy air-conditioned afternoons, lazy and drunk, blinds closed against the glare, empty sugar packets and dried-up orange peels strewn on the carpet, “Dear Prudence” from the White Album (which Boris adored) or else the same mournful old Radiohead over and over:

For a minute

I lost myself, I lost myself…

The glue we sniffed came on with a dark, mechanical roar, like the windy rush of propellers: engines on! We fell back on the bed into darkness, like sky divers tumbling backwards out of a plane, although—that high, that far gone—you had to be careful with the bag over your face or else you were picking dried blobs of glue out of your hair and off the end of your nose when you came to. Exhausted sleep, spine to spine, in dirty sheets that smelled of cigarette ash and dog, Popchik belly-up and snoring, subliminal whispers in the air blowing from the wall vents if you listened hard enough. Whole months passed where the wind never stopped, blown sand rattling against the windows, the surface of the swimming pool wrinkled and sinister-looking. Strong tea in the mornings, stolen chocolate. Boris yanking my hair by the handful and kicking me in the ribs. Wake up, Potter. Rise and shine.

I told myself I didn’t miss him, but I did. I got stoned alone, watched Adult Access and the Playboy channel, read Grapes of Wrath and The House of the Seven Gables which seemed as if they had to be tied for the most boring book ever written, and for what felt like thousands of hours—time enough to learn Danish or play the guitar if I’d been trying—fooled around in the street with a fucked-up skateboard Boris and I had found in one of the foreclosed houses down the block. I went to swim-team parties with Hadley—no-drinking parties, with parents present—and, on the weekends, attended parents-away parties of kids I barely knew, Xanax bars and Jägermeister shots, riding home on the hissing CAT bus at two a.m. so fucked up that I had to hold the seat in front of me to keep from falling out in the aisle. After school, if I was bored, it was easy enough to go hang out with one of the big lackadaisical stoner crowds who floated around between Del Taco and the kiddie arcades on the Strip.

But still I was lonely. It was Boris I missed, the whole impulsive mess of him: gloomy, reckless, hot-tempered, appallingly thoughtless. Boris pale and pasty, with his shoplifted apples and his Russian-language novels, gnawed-down fingernails and shoelaces dragging in the dust. Boris—budding alcoholic, fluent curser in four languages—who snatched food from my plate when he felt like it and nodded off drunk on the floor, face red like he’d been slapped. Even when he took things without asking, as he all too frequently did—little things were always disappearing, DVDs and school supplies from my locker, more than once I’d caught him going through my pockets for money—his own possessions meant so little to him that somehow it wasn’t stealing; whenever he came into cash himself, he split it with me down the middle and anything that belonged to him, he gave me gladly if I asked for it (and sometimes when I didn’t, as when Mr. Pavlikovsky’s gold lighter, which I’d admired in passing, turned up in the outside pocket of my backpack).

The funny thing: I’d worried, if anything, that Boris was the one who was a little too affectionate, if affectionate is the right word. The first time he’d turned in bed and draped an arm over my waist, I lay there half-asleep for a moment, not knowing what to do: staring at my old socks on the floor, empty beer bottles, my paperbacked copy of The Red Badge of Courage. At last—embarrassed—I faked a yawn and tried to roll away, but instead he sighed and pulled me closer, with a sleepy, snuggling motion.

Ssh, Potter, he whispered, into the back of my neck. Is only me.

It was weird. Was it weird? It was; and it wasn’t. I’d fallen back to sleep shortly after, lulled by his bitter, beery unwashed smell and his breath easy in my ear. I was aware I couldn’t explain it without making it sound like more than it was. On nights when I woke strangled with fear there he was, catching me when I started up terrified from the bed, pulling me back down in the covers beside him, muttering in nonsense Polish, his voice throaty and strange with sleep. We’d drowse off in each other’s arms, listening to music from my iPod (Thelonious Monk, the Velvet Underground, music my mother had liked) and sometimes wake clutching each other like castaways or much younger children.

And yet (this was the murky part, this was what bothered me) there had also been other, way more confusing and fucked-up nights, grappling around half-dressed, weak light sliding in from the bathroom and everything haloed and unstable without my glasses: hands on each other, rough and fast, kicked-over beers foaming on the carpet—fun and not that big of a deal when it was actually happening, more than worth it for the sharp gasp when my eyes rolled back and I forgot about everything; but when we woke the next morning stomach-down and groaning on opposite sides of the bed it receded into an incoherence of backlit flickers, choppy and poorly lit like some experimental film, the unfamiliar twist of Boris’s features fading from memory already and none of it with any more bearing on our actual lives than a dream. We never spoke of it; it wasn’t quite real; getting ready for school we threw shoes, splashed water at each other, chewed aspirin for our hangovers, laughed and joked around all the way to the bus stop. I knew people would think the wrong thing if they knew, I didn’t want anyone to find out and I knew Boris didn’t either, but all the same he seemed so completely untroubled by it that I was fairly sure it was just a laugh, nothing to take too seriously or get worked up about. And yet, more than once, I had wondered if I should step up my nerve and say something: draw some kind of line, make things clear, just to make absolutely sure he didn’t have the wrong idea. But the moment had never come. Now there was no point in speaking up and being awkward about the whole thing, though I scarcely took comfort in the fact.

I hated how much I missed him. There was a lot of drinking going on at my house, on Xandra’s end anyway, a lot of slammed doors (“Well, if it wasn’t me, it had to be you,” I heard her yelling); and without Boris there (they were both more constrained with Boris in the house) it was harder. Part of the problem was that Xandra’s hours at the bar had changed—schedules at her work had been moved; she was under a lot of stress, people she’d worked with were gone, or on different shifts; on Wednesdays and Mondays when I got up for school, I often found her just in from work, sitting alone in front of her favorite morning show too wired to sleep and swigging Pepto-Bismol straight from the bottle.

“Big old exhausted me,” she said, with an attempt at a smile, when she saw me on the stairs.

“You should go for a swim. That’ll make you sleepy.”

“No thanks, I think I’ll just hang out here with my Pepto. What a product. This is definitely some bubble-gum flavored awesomeness.”

As for my dad: he was spending a lot more time at home—hanging out with me, which I enjoyed, though his mood swings wore me out. It was football season; he had a bounce in his step. After checking his BlackBerry he high-fived me and danced around the living room: “Am I a genius or what? What?” He consulted spread breakdowns, matchup reports, and—occasionally—a paperbacked book called Scorpio: Your Sports Year in Forecast. “Always looking for an edge,” he said, when I found him running down the tables and punching out numbers on the calculator like he was figuring out his income tax. “You only have to hit fifty-three, fifty-four percent to grind out a good living on this stuff—see, baccarat is strictly for entertainment, there’s no skill to it, I set myself limits and never go over, but you can really make money at the sports book if you’re disciplined about it. You have to approach it like an investor. Not like a fan, not even like a gambler because the secret is, the better team usually wins the game and the linemaker is good at setting the number. Your linemaker has got limitations, though, as to public opinion. What he’s predicting is not who’s going to win but who the general public thinks is going to win. So that margin, between sentimental favorite and actual fact—fuck, see that receiver in the end zone, another big one for Pittsburgh right there, we need them to score now like we need a hole in the head—anyway, like I was saying, if I really sit down and do my homework as opposed to Joe Beefburger who picks his team by looking five minutes at the sports page? Who’s got the advantage? See, I’m not one of these saps that gets all starry-eyed about the Giants rain or shine—shit, your mother could have told you that. Scorpio is about control—that’s me. I’m competitive. Want to win at any price. That’s where my acting came from, back when I acted. Sun in Scorpio, Leo rising. All in my chart. Now you’re a Cancer, hermit crab, all secretive and up in your shell, completely different MO. It’s not bad, it’s not good, it’s just how it is. Anyway, whatever, I always take my lead from my defensive-offensive lines, but all the same it never hurts to pay attention to these transits and solar-arc progressions on game day—”

“Did Xandra get you interested in all this?”

“Xandra? Half the sports book in Vegas has an astrologer on speed dial. Anyway, like I was saying, all other things equal, do the planets make a difference? Yes. I would definitely have to say yes. It’s like, is a player having a good day, is he having a bad day, is he out of sorts, whatever. Honestly it helps to have that edge when you’re getting a little, how do I put it, ha ha, stretched, although—” he showed me the fat wad of what looked like hundreds, wrapped with a rubber band—“this has been a really amazing year for me. Fifty-three percent, a thousand plays a year. That’s the magic spot.”

Sundays were what he called major-ticket days. When I got up, I found him downstairs in a crackle of strewn newspapers, zinging around bright and restless like it was Christmas morning, opening and shutting cabinets, talking to the sports ticker on his BlackBerry and crunching on corn chips straight from the bag. If I came down and watched with him for even a little while when the big games were on sometimes he’d give me what he called “a piece—” twenty bucks, fifty, if he won. “To get you interested,” he explained, leaning forward on the sofa, rubbing his hands anxiously. “See—what we need is for the Colts to get wiped off the map during this first half of the game. Devastated. And with the Cowboys and the Niners we need the score to go over thirty in the second half—yes!” he shouted, jumping up exhilarated with raised fist. “Fumble! Redskins got the ball. We’re in business!”

But it was confusing, because it was the Cowboys who had fumbled. I’d thought the Cowboys were supposed to win by at least fifteen. His mid-game switches in loyalty were too abrupt for me to follow and I often embarrassed myself by cheering for the wrong team; yet as we surged randomly between games, between spreads, I enjoyed his delirium and the daylong binge of greasy food, accepted the twenties and fifties he tossed at me as if they’d fallen from the sky. Other times—cresting and then tanking on some hoarse wave of enthusiasm—a vague unease took hold of him which as far as I could tell had nothing very much to do with how his games were going and he paced back and forth for no reason I could discern, hands folded atop his head, staring at the set with the air of a man unhinged by business failure: talking to the coaches, the players, asking what the hell was wrong with them, what the hell was happening. Sometimes he followed me into the kitchen, with an oddly supplicant demeanor. “I’m getting killed in there,” he said, humorously, leaning on the counter, his bearing comical, something in his hunched posture suggesting a bank robber doubled over from a gunshot wound.

Lines x. Lines y. Yards run, cover the spread. On game day, until five o’clock or so, the white desert light held off the essential Sunday gloom—autumn sinking into winter, loneliness of October dusk with school the next day—but there was always a long still moment toward the end of those football afternoons where the mood of the crowd turned and everything grew desolate and uncertain, onscreen and off, the sheet-metal glare off the patio glass fading to gold and then gray, long shadows and night falling into desert stillness, a sadness I couldn’t shake off, a sense of silent people filing toward the stadium exits and cold rain falling in college towns back east.

The panic that overtook me then was hard to explain. Those game days broke up with a swiftness, a sense of losing blood almost, that reminded me of watching the apartment in New York being boxed up and carted away: groundlessness and flux, nothing to hang on to. Upstairs, with the door of my room shut, I turned all the lights on, smoked weed if I had it, listened to music on my portable speakers—previously unlistened-to music like Shostakovich, and Erik Satie, that I’d put on my iPod for my mother and then never got around to taking off—and I looked at library books: art books, mostly, because they reminded me of her.

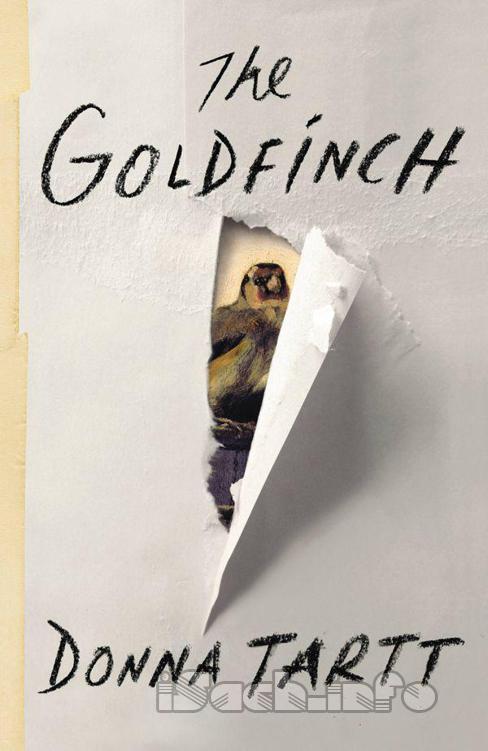

The Masterworks of Dutch Painting. Delft: The Golden Age. Drawings by Rembrandt, His Anonymous Pupils and Followers. From looking on the computer at school, I’d seen that there was a book about Carel Fabritius (a tiny book, only a hundred pages) but they didn’t have it at the school library and our computer time at school was so closely monitored that I was too paranoid to do any research on line—especially after a thoughtlessly clicked link (Het Puttertje, The Goldfinch, 1654) had taken me to a scarily official-looking site called Missing Art Database that required me to sign in with my name and address. I’d been so freaked out at the unexpected sight of the words Interpol and Missing that I’d panicked and shut down the computer entirely, something we weren’t supposed to do. “What have you just done?” demanded Mr. Ostrow the librarian before I was able to get it back up again. He reached over my shoulder and began typing in the password.

“I—” In spite of myself, I was relieved that I hadn’t been looking at porn once he began surfing back through the history. I’d meant to buy myself a cheap laptop with the five hundred bucks my dad had given me for Christmas, but somehow that money had gotten away from me—Missing Art, I told myself; no reason to panic over that word missing, destroyed art was missing art, wasn’t it? Even though I hadn’t put down a name, it worried me that I’d tried to check out the database from my school’s IP address. For all I knew, the investigators who’d been to see me had kept track, and knew that I was in Vegas; the connection, though small, was real.

The painting was hidden, quite cleverly as I thought, in a clean cotton pillowcase duct-taped to the back of my headboard. I’d learned, from Hobie, how carefully old things had to be handled (sometimes he used white cotton gloves for particularly delicate objects) and I never touched it with my bare hands, only by the edges. I never took it out except when Dad and Xandra weren’t there and I knew they wouldn’t be back for a while—though even when I couldn’t see it I liked knowing it was there for the depth and solidity it gave things, the reinforcement to infrastructure, an invisible, bedrock rightness that reassured me just as it was reassuring to know that far away, whales swam untroubled in Baltic waters and monks in arcane time zones chanted ceaselessly for the salvation of the world.

Taking it out, handling it, looking at it, was nothing to be done lightly. Even in the act of reaching for it there was a sense of expansion, a waft and a lifting; and at some strange point, when I’d looked at it long enough, eyes dry from the refrigerated desert air, all space appeared to vanish between me and it so that when I looked up it was the painting and not me that was real.

1622–1654. Son of a schoolteacher. Fewer than a dozen works accurately attributed to him. According to van Bleyswijck, the city historian of Delft, Fabritius was in his studio painting the sexton of Delft’s Oude Kerk when, at half past ten in the morning, the explosion of the powder magazine took place. The body of the painter Fabritius had been pulled from the wreckage of his studio by neighboring burghers, “with great sorrow,” the books said, “and no little effort.” What held me fast in these brief library-book accounts was the element of chance: random disasters, mine and his, converging on the same unseen point, the big bang as my father called it, not with any kind of sarcasm or dismissiveness but instead a respectful acknowledgment for the powers of fortune that governed his own life. You could study the connections for years and never work it out—it was all about things coming together, things falling apart, time warp, my mother standing out in front of the museum when time flickered and the light went funny, uncertainties hovering on the edge of a vast brightness. The stray chance that might, or might not, change everything.

Upstairs, the tap water from the bathroom sink was too chlorinated to drink. Nights, a dry wind blew trash and beer cans down the street. Moisture and humidity, Hobie had told me, were the worst things in the world for antiques; on the tall-case clock he’d been repairing when I left, he’d showed me how the wood had been rotted out underneath from the damp (“someone sluicing stone floors with a bucket, you see how soft this wood is, how worn away?”)

Time warp: a way of seeing things twice, or more than twice. Just as my dad’s rituals, his betting systems, all his oracles and magic were predicated on a field awareness of unseen patterns, so too the explosion in Delft was part of a complex of events that ricocheted into the present. The multiple outcomes could make you dizzy. “The money’s not important,” said my dad. “All money represents is the energy of the thing, you know? It’s how you track it. The flow of chance.” Steadily the goldfinch gazed at me, with shiny, changeless eyes. The wooden panel was tiny, “only slightly larger than an A-4 sheet of paper” as one of my art books had pointed out, although all that dates-and-dimensions stuff, the dead textbook info, was as irrelevant in its way as the sports-page stats when the Packers were up by two in the fourth quarter and a thin icy snow had begun to fall on the field. The painting, the magic and aliveness of it, was like that odd airy moment of the snow falling, greenish light and flakes whirling in the cameras, where you no longer cared about the game, who won or lost, but just wanted to drink in that speechless windswept moment. When I looked at the painting I felt the same convergence on a single point: a flickering sun-struck instant that existed now and forever. Only occasionally did I notice the chain on the finch’s ankle, or think what a cruel life for a little living creature—fluttering briefly, forced always to land in the same hopeless place.

v.

THE GOOD THING: I was pleased at how nice my dad was being. He’d been taking me out to dinners—nice dinners, at white-tablecloth restaurants, just the two of us—at least once a week. Sometimes he invited Boris to come, invitations Boris always jumped to accept—the lure of a good meal was powerful enough to override even the gravitational tug of Kotku—but strangely, I found myself enjoying it more when it was just my dad and me.

“You know,” he said, at one of these dinners when we were lingering late over dessert—talking about school, about all sorts of things (this new, involved dad! where had he come from?)—“you know, I really have enjoyed getting to know you since you’ve been out here, Theo.”

“Well, uh, yeah, me too,” I said, embarrassed but also meaning it.

“I mean—” my dad ran a hand through his hair—“thanks for giving me a second chance, kiddo. Because I made a huge mistake. I never should have let my relationship with your mother get in the way of my relationship with you. No, no,” he said, raising his hand, “I’m not blaming anything on your mom, I’m way past that. It’s just that she loved you so much, I always felt like kind of an interloper with you guys. Stranger-in-my-own-house kind of thing. You two were so close—” he laughed, sadly—“there wasn’t much room for three.”

“Well—” My mother and I tiptoeing around the apartment, whispering, trying to avoid him. Secrets, laughter. “I mean, I just—”

“No, no, I’m not asking you to apologize. I’m the dad, I’m the one who should have known better. It’s just that it got to be a kind of vicious circle if you know what I mean. Me feeling alienated, bummed-out, drinking a lot. And I never should have let that happen. I missed, like, some really important years in your life. I’m the one that has to live with that.”

“Um—” I felt so bad I didn’t know what to say.

“Not trying to put you on the spot, pal. Just saying I’m glad that we’re friends now.”

“Well yeah,” I said, staring into my scraped-clean crème brûlée plate, “me too.”

“And, I mean—I want to make it up to you. See, I’m doing so well on the sports book this year—” my dad took a sip of his coffee—“I want to open you a savings account. You know, just put a little something aside. Because, you know, I really didn’t do right by you as far as your mom, you know, and all those months that I was gone.”

“Dad,” I said, disconcerted. “You don’t have to do that.”

“Oh, but I want to! You have a Social Security number, don’t you?”

“Sure.”

“Well, I’ve already got ten thousand set aside. That’s a good start. If you think about it when we get home, give me your Social and next time I drop by the bank, I’ll open an account in your name, okay?”

vi.

APART FROM SCHOOL, I’D hardly seen Boris, except for a Saturday afternoon trip when my dad had taken us in to the Carnegie Deli at the Mirage for sable and bialys. But then, a few weeks before Thanksgiving, he came thumping upstairs when I wasn’t expecting him and said: “Your dad has been having a bad run, did you know that?”

I put down Silas Marner, which we were reading for school. “What?”

“Well, he’s been playing at two hundred dollar tables—two hundred dollars a pop,” he said. “You can lose a thousand in five minutes, easy.”

“A thousand dollars is nothing for him,” I said; and then, when Boris did not reply: “How much did he say he lost?”

“Didn’t say,” said Boris. “But a lot.”

“Are you sure he wasn’t just bullshitting you?”

Boris laughed. “Could be,” he said, sitting on the bed and leaning back on his elbows. “You don’t know anything about it?”

“Well—” As far as I knew, my father had cleaned up when the Bills had won the week before. “I don’t see how he can be doing too bad. He’s been taking me to Bouchon and places like that.”

“Yes, but maybe is good reason for that,” said Boris sagely.

“Reason? What reason?”

Boris seemed about to say something, then changed his mind.

“Well, who knows,” he said, lighting a cigarette and taking a sharp drag. “Your dad—he’s part Russian.”

“Right,” I said, reaching for the cigarette myself. I’d often heard Boris and my father, in their arm-waving “intellectual talks,” discussing the many celebrated gamblers in Russian history: Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, other names I didn’t know.

“Well—very Russian, you know, to complain how bad things are all the time! Even if life is great—keep it to yourself. You don’t want to tempt the devil.” He was wearing a discarded dress shirt of my father’s, washed nearly transparent and so big that it billowed on him like some item of Arab or Hindu costume. “Only, your dad, sometimes is hard to tell between joking and serious.” Then, watching me carefully: “What are you thinking?”

“Nothing.”

“He knows we talk. That’s why he told me. He wouldn’t tell me if he didn’t want you to know.”

“Yeah.” I was fairly sure this wasn’t the case. My dad was the kind of guy who in the right mood would happily discuss his personal life with his boss’s wife or some other inappropriate person.

“He’d tell you himself,” said Boris, “if he thought you wanted to know.”

“Look. Like you said—” My dad had a taste for masochism, the overblown gesture; on our Sundays together, he loved to exaggerate his misfortunes, groaning and staggering, complaining loudly of being ‘wiped out’ or ‘destroyed’ after a lost game even as he’d won half a dozen others and was totting up the profits on the calculator. “Sometimes he lays it on a bit thick.”

“Well, yes, is true,” said Boris sensibly. He took the cigarette back, inhaled, and then, companionably, passed it to me. “You can have the rest.”

“No, thanks.”

There was a bit of a silence, during which we could hear the television crowd roar of my dad’s football game. Then Boris leaned back on his elbows again and said: “What is there to eat downstairs?”

“Not a motherfucking thing.”

“There was leftover Chinese, I thought.”

“Not any more. Somebody ate it.”

“Shit. Maybe I’ll go to Kotku’s, her mom has frozen pizzas. You want to come?”

“No, thanks.”

Boris laughed, and threw out some fake-looking gang sign. “Suit yourself, yo,” he said, in his “gangsta” voice (discernible from his regular voice only by the hand gesture and the “yo”) as he got up and roll-walked out. “Nigga gotz to eat.”

vii.

THE PECULIAR THING ABOUT Boris and Kotku was how rapidly their relationship had taken on a punchy, irritable quality. They still made out constantly, and could hardly keep their hands off each other, but the minute they opened their mouths it was like listening to people who had been married fifteen years. They bickered over small sums of money, like who had paid for their food-court lunches last; and their conversations, when I could overhear them, went something like this:

Boris: “What! I was trying to be nice!”

Kotku: “Well, it wasn’t very nice.”

Boris, running to catch up with her: “I mean it, Kotyku! Honest! Was only trying to be nice!”

Kotku: [pouting]

Boris, trying unsuccessfully to kiss her: “What did I do? What’s the matter? Why do you think I’m not nice any more?”

Kotku: [silence]

The problem of Mike the pool man—Boris’s romantic rival—had been solved by Mike’s extremely convenient decision to join the Coast Guard. Kotku, apparently, still spent hours on the phone with him every week, which for whatever reason didn’t trouble Boris (“She’s only trying to support him, see”). But it was disturbing how jealous he was of her at school. He knew her schedule by heart and the second our classes were over he raced to find her, as if he suspected her of two-timing him during Spanish for the Workplace or whatever. One day after school, when Popper and I were by ourselves at home, he telephoned me to ask: “Do you know some guy named Tyler Olowska?”

“No.”

“He’s in your American History class.”

“Sorry. It’s a big class.”

“Well, look. Can you find out about him? Where he lives maybe?”

“Where he lives? Is this about Kotku?”

All of a sudden—surprising me greatly—the doorbell rang: four stately chimes. In all my time in Las Vegas no one had ever rung the doorbell of our house, not even once. Boris, on the other end, had heard it too. “What is that?” he said. The dog was running in circles and barking his head off.

“Someone at the door.”

“The door?” On our deserted street—no neighbors, no garbage pickup, no streetlights even—this was a major event. “Who do you think it is?”

“I don’t know. Let me call you back.”

I grabbed up Popchyk—who was practically hysterical—and (as he wriggled and shrieked in my arms, struggling to get down) managed to get the door open with one hand.

“Wouldja look at that,” a pleasant, Jersey-accented voice said. “What a cute little fella.”

I found myself blinking up in the late afternoon glare at a very tall, very very tanned, very thin man, of indeterminate age. He looked partly like a rodeo guy and partly like a fucked-up lounge entertainer. His gold-rimmed aviators were tinted purple at the top; he was wearing a white sports jacket over a red cowboy shirt with pearl snaps, and black jeans, but the main thing I noticed was his hair: part toupee, part transplanted or sprayed-on, with a texture like fiberglass insulation and a dark brown color like shoe polish in the tin.

“Go on, put him down!” he said, nodding at Popper, who was still struggling to get away. His voice was deep, and his manner calm and friendly; except for the accent he was the perfect Texan, boots and all. “Let him run around! I don’t mind. I love dogs.”

When I let Popchyk loose, he stooped to pat his head, in a posture reminiscent of a lanky cowboy by the campfire. As odd as the stranger looked, with the hair and all, I couldn’t help but admire how easy and comfortable he seemed in his skin.

“Yeah, yeah,” he said. “Cute little fella. Yes you are!” His tanned cheeks had a wrinkled, dried-apple quality, creased with tiny lines. “Have three of my own at home. Mini pennys.”

“Excuse me?”

He stood; when he smiled at me, he displayed even, dazzlingly white teeth.

“Miniature pinschers,” he said. “Neurotic little bastards, chew the house to pieces when I’m gone, but I love them. What’s your name, kid?”

“Theodore Decker,” I said, wondering who he was.

Again he smiled; his eyes behind the semi-dark aviators were small and twinkly. “Hey! Another New Yorker! I can hear it in your voice, am I right?”

“That’s right.”

“A Manhattan boy, that would be my guess. Correct?”

“Right,” I said, wondering exactly what it was in my voice that he’d heard. No one had ever guessed I was from Manhattan just from hearing me talk.

“Well, hey—I’m from Canarsie. Born and bred. Always nice to meet another guy from back East. I’m Naaman Silver.” He held out his hand.

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Silver.”

“Mister!” He laughed fondly. “I love a polite kid. They don’t make many like you any more. You Jewish, Theodore?”

“No, sir,” I said, and then wished I’d said yes.

“Well, tell you what. Anybody from New York, in my book they’re an honorary Jew. That’s how I look at it. You ever been to Canarsie?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, it used to be a fantastic community back in the day, though now—” He shrugged. “My family, they were there for four generations. My grandfather Saul ran one of the first kosher restaurants in America, see. Big, famous place. Closed when I was a kid, though. And then my mother moved us over to Jersey after my father died so we could be closer to my uncle Harry and his family.” He put his hand on his thin hip and looked at me. “Your dad here, Theo?”

“No.”

“No?” He looked past me, into the house. “That’s a shame. Know when he’ll be back?”

“No, sir,” I said.

“Sir. I like that. You’re a good kid. Tell you what, you remind me of myself at your age. Fresh from yeshiva—” he held up his hands, gold bracelets on the tanned, hairy wrists—“and these hands? White, like milk. Like yours.”

“Um”—I was still standing awkwardly in the door—“would you like to come in?” I wasn’t sure if I should invite a stranger in the house, except I was lonely and bored. “You can wait if you want. But I’m not sure when he’ll be home.”

Again, he smiled. “No thanks. I have a bunch of other stops to make. But I’ll tell you what, I’m gonna be straight with you, because you’re a nice kid. I got five points on your dad. You know what that means?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, bless you. You don’t need to know, and I hope you never do know. But let me just say it aint a good business policy.” He put a friendly hand on my shoulder. “Believe it or not, Theodore, I got people skills. I don’t like to come to a man’s home and deal with his child, like I’m doing with you now. That’s not right. Normally I would go to your dad’s place of work and we would have our little sit-down there. Except he’s kind of a hard man to run down, as maybe you already know.”

In the house I could hear the telephone ringing: Boris, I was fairly sure. “Maybe you better go answer that,” said Mr. Silver pleasantly.

“No, that’s okay.”

“Go ahead. I think maybe you should. I’ll be waiting right here.”

Feeling increasingly disturbed I went back in and answered the telephone. As predicted, it was Boris. “Who was that?” he said. “Not Kotku, was it?”

“No. Look—”

“I think she went home with that Tyler Olowska guy. I got this funny feeling. Well, maybe she didn’t go home home with him. But they left school together—she was talking to him in the parking lot. See, she has her last class with him, woodwork skills or whatever—”

“Boris, I’m sorry, I really can’t talk now, I’ll call you back, okay?”

“I’m taking your word for it that wasn’t your dad in there on the horn,” said Mr. Silver when I returned to the door. I looked past him, to the white Cadillac parked by the curb. There were two men in the car—a driver, and another man in the front seat. “That wasn’t your dad, right?”

“No sir.”

“You would tell me if it was, wouldn’t you?”

“Yes sir.”

“Why don’t I believe you?”

I was silent, not knowing what to say.

“Doesn’t matter, Theodore.” Again, he stooped to scratch Popper behind the ears. “I’ll run him down sooner or later. You’ll be sure to remember what I told him? And that I stopped by?”

“Yes sir.”

He pointed a long finger at me. “What’s my name again?”

“Mr. Silver.”

“Mr. Silver. That’s right. Just checking.”

“What do you want me to tell him?”

“Tell him I said gambling’s for tourists,” he said. “Not locals.” Lightly, lightly, with his thin brown hand, he touched me on the top of the head. “God bless.”

viii.

WHEN BORIS SHOWED UP at the door around half an hour later, I tried to tell him about the visit from Mr. Silver, but though he listened, a little, mainly he was furious at Kotku for flirting with some other boy, this Tyler Olowska or whatever, a rich stoner kid a year older than us who was on the golf team. “Fuck her,” he said throatily while we were sitting on the floor downstairs at my house smoking Kotku’s pot. “She’s not answering her phone. I know she’s with him now, I know it.”

“Come on.” As worried as I was about Mr. Silver, I was even more sick of talking about Kotku. “He was probably just buying some weed.”

“Yah, but is more to it, I know. She never wants me to stay over with her any more, have you noticed that? Always has stuff to do now. She’s not even wearing the necklace I bought her.”

My glasses were lopsided and I pushed them back up on the bridge of my nose. Boris hadn’t even bought the stupid necklace but shoplifted it at the mall, snatching it and running out while I (upstanding citizen, in school blazer) occupied the salesgirl’s attention with dumb but polite questions about what Dad and I ought to get Mom for her birthday. “Huh,” I said, trying to sound sympathetic.

Boris scowled, his brow like a thundercloud. “She’s a whore. Other day? Was pretending to cry in class—trying to make this Olowska bastard feel sorry for her. What a cunt.”

I shrugged—no argument from me on that point—and passed him the reefer.

“She only likes him because he has money. His family has two Mercedes. E class.”

“That’s an old lady car.”

“Nonsense. In Russia, is what mobsters drive. And—” he took a deep hit, holding it in, waving his hands, eyes watering, wait, wait, this is the best part, hold on, get this, would you?—“you know what he calls her?”

“Kotku?” Boris was so insistent about calling her Kotku that people at school—teachers, even—had begun calling her Kotku as well.

“That’s right!” said Boris, outraged, smoke erupting from his mouth. “My name! The kliytchka I gave her. And, other day in the hallway? I saw him ruffle her on the head.”

There were a couple of half-melted peppermints from my dad’s pocket on the coffee table, along with some receipts and change, and I unwrapped one and put it in my mouth. I was as high as a paratrooper and the sweetness tingled all through me, like fire. “Ruffled her?” I said, the candy clicking loudly against my teeth. “Come again?”

“Like this,” he said, making a tousling motion with his hand as he took one last hit off the joint and stubbed it out. “Don’t know the word.”

“I wouldn’t worry about it,” I said, rolling my head back against the couch. “Say, you ought to try one of these peppermints. They taste really great.”

Boris scrubbed a hand down his face, then shook his head like a dog throwing off water. “Wow,” he said, running both hands through his tangled-up hair.

“Yeah. Me too,” I said, after a vibrating pause. My thoughts were stretched-out and viscid, slow to wade to the surface.

“What?”

“I’m fucked up.”

“Oh yeah?” He laughed. “How fucked up?”

“Pretty far up there, pal.” The peppermint on my tongue felt intense and huge, the size of a boulder, like I could hardly talk with it in my mouth.

A peaceful silence followed. It was about five thirty in the afternoon but the light was still pure and stark. Some white shirts of mine were hanging outside by the pool and they were dazzling, billowing and flapping like sails. I closed my eyes, red burning through my eyelids, sinking back into the (suddenly very comfortable) couch as if it were a rocking boat, and thought about the Hart Crane we’d been reading in English. Brooklyn Bridge. How had I never read that poem back in New York? And how had I never paid attention to the bridge when I saw it practically every day? Seagulls and dizzying drops. I think of cinemas, panoramic sleights…

“I could strangle her,” Boris said abruptly.

“What?” I said, startled, having heard only the word strangle and Boris’s unmistakably ugly tone.

“Scrawny fucking bint. She makes me so mad.” Boris nudged me with his shoulder. “Come on, Potter. Wouldn’t you like to wipe that smirk off her face?”

“Well…” I said, after a dazed pause; clearly this was a trick question. “What’s a bint?”

“Same as a cunt, basically.”

“Oh.”

“I mean, who does she.”

“Right.”

There followed a long and weird enough silence that I thought about getting up and putting some music on, although I couldn’t decide what. Anything upbeat seemed wrong and the last thing I wanted to do was put on something dark or angsty that would get him stirred up.

“Um,” I said, after what I hoped was a decently long pause, “The War of the Worlds comes on in fifteen minutes.”

“I’ll give her War of the Worlds,” said Boris darkly. He stood up.

“Where are you going?” I said. “To the Double R?”

Boris scowled. “Go ahead, laugh,” he said bitterly, elbowing on his gray sovietskoye raincoat. “It’s going to be the Three Rs for your dad if he doesn’t pay the money he owes that guy.”

“Three Rs?”

“Revolver, roadside, or roof,” said Boris, with a black, Slavic-sounding chuckle.

ix.

WAS THAT A MOVIE or something? I wondered. Three Rs? Where had he come up with that? Though I’d done a fairly good job of putting the afternoon’s events out of my mind, Boris had thoroughly freaked me out with his parting comment and I sat downstairs rigidly for an hour or so with War of the Worlds on but the sound off, listening to the crash of the icemaker and the rattle of wind in the patio umbrella. Popper, who had picked up on my mood, was just as keyed-up as I was and kept barking sharply and hopping off the sofa to check out noises around the house—so that when, not long after dark, a car did actually turn into the driveway, he dashed to the door and set up a racket that scared me half to death.

But it was only my father. He looked rumpled and glazed, and not in a very good mood.

“Dad?” I was still high enough that my voice came out sounding way too blown and odd.

He stopped at the foot of the stairs and looked at me.

“There was a guy here. A Mr. Silver.”

“Oh, yeah?” said my dad, casually enough. But he was standing very still with his hand on the banister.

“He said he was trying to get in touch with you.”

“When was this?” he said, coming into the room.

“About four this afternoon, I guess.”

“Was Xandra here?”

“I haven’t seen her.”

He lay a hand on my shoulder, and seemed to think for a minute. “Well,” he said, “I’d appreciate if you didn’t say anything about it.”

The end of Boris’s joint was, I realized, still in the ashtray. He saw me looking at it, and picked it up and sniffed it.

“Thought I smelled something,” he said, dropping it in his jacket pocket. “You reek a bit, Theo. Where have you boys been getting this?”

“Is everything okay?”

My dad’s eyes looked a bit red and unfocused. “Sure it is,” he said. “I’m just going to go upstairs and make a few calls.” He gave off a strong odor of stale tobacco smoke and the ginseng tea he always drank, a habit he’d picked up from the Chinese businessmen in the baccarat salon: it gave his sweat a sharp, foreign smell. As I watched him walk up the steps to the landing, I saw him retrieve the joint-end from his jacket pocket and run it under his nose again, ruminatively.

x.

ONCE I WAS UPSTAIRS in my room, with the door locked, and Popper still edgy and pacing stiffly around—my thoughts went to the painting. I had been proud of myself for the pillowcase-behind-the-headboard idea, but now I realized how stupid it was to have the painting in the house at all—not that I had any options unless I wanted to hide it in the dumpster a few houses down (which had never been emptied the whole time I’d lived in Vegas) or over in one of the abandoned houses across the street. Boris’s house was no safer than mine, and there was no one else I knew well enough or trusted. The only other place was school, also a bad idea, but though I knew there had to be a better choice I couldn’t think of it. Every so often they had random locker inspections at school and now—connected as I was, through Boris, to Kotku—I was possibly the sort of dirtbag they might randomly inspect. Still, even if someone found it in my locker—whether the principal, or Mr. Detmars the scary basketball coach, or even the Rent-a-Cops from the security firm whom they brought in to scare the students from time to time—still, it would be better than having it found by Dad or Mr. Silver.

The painting, inside the pillowcase, was wrapped in several layers of taped drawing paper—good paper, archival paper, that I’d taken from the art room at school—with an inner, double layer of clean white cotton dishcloth to protect the surface from the acids in the paper (not that there were any). But I’d taken the painting out so often to look at it—opening the top flap of the taped edge to slide it out—that the paper was torn and the tape wasn’t even sticky any more. After lying in bed for a few minutes staring at the ceiling, I got up and retrieved the extra-large roll of heavy-duty packing tape left over from our move, and then untaped the pillowcase from behind the headboard.

Too much—too tempting—to have my hands on it and not look at it. Quickly I slid it out, and almost immediately its glow enveloped me, something almost musical, an internal sweetness that was inexplicable beyond a deep, blood-rocking harmony of rightness, the way your heart beat slow and sure when you were with a person you felt safe with and loved. A power, a shine, came off it, a freshness like the morning light in my old bedroom in New York which was serene yet exhilarating, a light that rendered everything sharp-edged and yet more tender and lovely than it actually was, and lovelier still because it was part of the past, and irretrievable: wallpaper glowing, the old Rand McNally globe in half-shadow.

Little bird; yellow bird. Shaking free of my daze I slid it back in the paper-wrapped dishtowel and wrapped it again with two or three (four? five?) of my dad’s old sports pages, then—impulsively, really getting into it in my own stoned, determined way—wound it around and around with tape until not a shred of newsprint was visible and the entire X-tra large roll of tape was gone. Nobody was going to be opening that package on a whim. Even if with a knife, a good one, not just scissors, it would take a good long time to get into it. At last, when I was done—the bundle looked like some weird science-fiction cocoon—I slipped the mummified painting, pillowcase and all, in my book bag, and put it under the covers by my feet. Irritably, with a groan, Popper shifted over to make room. Tiny as he was, and ridiculous-looking, still he was a fierce barker and territorial about his place next to me; and I knew if anyone opened the bedroom door while I was sleeping—even Xandra or my dad, neither of whom he liked much—he would jump up and raise the alarm.

What had started as a reassuring thought was once again morphing into thoughts of strangers and break-ins. The air conditioner was so cold I was shaking; and when I closed my eyes I felt myself lifting up out of my body—floating up fast like an escaped balloon—only to startle with a sharp full-body jerk when I opened my eyes. So I kept my eyes shut and tried to remember what I could of the Hart Crane poem, which wasn’t much, although even isolated words like seagull and traffic and tumult and dawn carried something of its airborne distances, its sweeps from high to low; and just as I was nodding off, I fell into sort of an overpowering sense-memory of the narrow, windy, exhaust-smelling park near our old apartment, by the East River, roar of traffic washing abstractly above as the river swirled with fast, confusing currents and sometimes appeared to flow in two different directions.

xi.

I DIDN’T SLEEP MUCH that night and was so exhausted by the time I got to school and stowed the painting in my locker that I didn’t even notice that Kotku (hanging all over Boris, like nothing had happened) was sporting a fat lip. Only when I heard this tough senior guy Eddie Riso say, “Mack truck?” did I see that somebody had smacked her pretty good in the face. She was going around laughing a bit nervously and telling people that she got hit in the mouth by a car door, but in a sort of embarrassed way that (to me, at least) didn’t ring true.

“Did you do that?” I said to Boris, when next I saw him alone (or relatively alone) in English class.

Boris shrugged. “I didn’t want to.”

“What do you mean, you ‘didn’t want to’?”

Boris looked shocked. “She made me!”

“She made you,” I repeated.

“Look, just because you’re jealous of her—”

“Fuck you,” I said. “I don’t give a shit about you and Kotku—I have things of my own to worry about. You can beat her head in for all I care.”

“Oh, God, Potter,” said Boris, suddenly sobered. “Did he come back? That guy?”

“No,” I said, after a brief pause. “Not yet. Well, I mean, fuck it,” I said, when Boris kept on staring at me. “It’s his problem, not mine. He’ll just have to figure something out.”

“How much is he in for?”

“No clue.”

“Can’t you get the money for him?”

“Me?”

Boris looked away. I poked him in the arm. “No, what do you mean, Boris? Can’t I get it for him? What are you talking about?” I said, when he didn’t answer.

“Never mind,” he said quickly, settling back in his chair, and I didn’t have a chance to pursue the conversation because then Spirsetskaya walked into the room, all primed to talk about boring Silas Marner, and that was it.

xii.

THAT NIGHT, MY DAD came home early with bags of carry-out from his favorite Chinese, including an extra order of the spicy dumplings I liked—and he was in such a good mood that it was as if I’d dreamed Mr. Silver and the stuff from the night before.

“So—” I said, and stopped. Xandra, having finished her spring rolls, was rinsing glasses at the sink but there was only so much I felt comfortable saying in front of her.

He smiled his big Dad smile at me, the smile that sometimes made stewardesses bump him up to first class.

“So what?” he said, pushing aside his carton of Szechuan shrimp to reach for a fortune cookie.

“Uh—” Xandra had the water up loud—“Did you get everything straightened out?”

“What,” he said lightly, “you mean with Bobo Silver?”

“Bobo?”

“Listen, I hope you weren’t worried about that. You weren’t, were you?”

“Well—”

“Bobo—” he laughed—“they call him ‘The Mensch.’ He’s actually a nice guy—well, you talked to him yourself—we just had some crossed wires, is all.”

“What does five points mean?”

“Look, it was just a mix-up. I mean,” he said, “these people are characters. They have their own language, their own ways of doing things. But, hey—” he laughed—“this is great—when I met with him over at Caesars, that’s what Bobo calls his ‘office,’ you know, the pool at Caesars—anyway, when I met with him, you know what he kept saying? ‘That’s a good kid you’ve got there, Larry.’ ‘Real little gentleman.’ I mean, I don’t know what you said to him, but I do actually owe you one.”

“Huh,” I said in a neutral voice, helping myself to more rice. But inwardly I was almost drunk at the lift in his mood—the same flood of elation I’d felt as a small child when the silences broke, when his footsteps grew light again and you heard him laughing at something, humming at the shaving mirror.

My dad cracked open his fortune cookie, and laughed. “See here,” he said, balling it up and tossing it over to me. “I wonder who sits around in Chinatown and thinks up these things?”

Aloud, I read it: “ ‘You have an unusual equipment for fate, exercise with care!’ ”

“Unusual equipment?” said Xandra, coming up behind to put her arms around his neck. “That sounds kind of dirty.”

“Ah—” my dad turned to kiss her. “A dirty mind. The fountain of youth.”

“Apparently.”

xiii.

“I GAVE you a fat lip that time,” said Boris, who clearly felt guilty about the Kotku business since he’d brought it up out of nowhere in our companionable morning silence on the school bus.

“Yeah, and I knocked your head against the fucking wall.”

“I didn’t mean to!”

“Didn’t mean what?”

“To hit you in the mouth!”

“You meant it with her?”

“In a way, yeah,” he said evasively.

“In a way.”

Boris made an exasperated sound. “I told her I was sorry! Everything is fine with us now, no problem! And besides, what business is it of yours?”

“You brought it up, not me.”

He looked at me for an odd, off-centered moment, then laughed. “Can I tell you something?”

“What?”

He put his head close to mine. “Kotku and me tripped last night,” he said quietly. “Dropped acid together. It was great.”

“Really? Where did you get it?” E was easy enough to find at our school—Boris and I had taken it at least a dozen times, magical speechless nights where we had walked into the desert half-delirious at the stars—but nobody ever had acid.

Boris rubbed his nose. “Ah. Well. Her mom knows this scary old guy named Jimmy that works at a gun shop. He hooked us up with five hits—I don’t know why I bought five, I wish I’d bought six. Anyway I still have some. God it was fantastic.”

“Oh, yeah?” Now that I looked at him more closely, I realized that his pupils were dilated and strange. “Are you still on it?”

“Maybe a little. I only slept like two hours. Anyway we totally made up. It was like—even the flowers on her mom’s bedspread were friendly. And we were made out of the same stuff as the flowers, and we realized how much we loved each other, and needed each other no matter what, and how everything hateful that had happened between us was only out of love.”

“Wow,” I said, in a voice that I guess must have sounded sadder than I’d intended, from the way that Boris brought his eyebrows together and looked at me.

“Well?” I said, when he kept on staring at me. “What is it?”

He blinked and shook his head. “No, I can just see it. This mist of sadness, sort of, around your head. It’s like you’re a soldier or something, a person from history, walking on a battlefield maybe with all these deep feelings…”

“Boris, you’re still completely fried.”

“Not really,” he said dreamily. “I sort of snap in and out of it. But I still see colored sparks coming off things if I look from the corner of my eye just right.”

xiv.

A WEEK OR SO passed, without incident, either with my dad or on the Boris-Kotku front—enough time that I felt safe bringing the pillowcase home. I had noticed, when taking it out of my locker, how unusually bulky (and heavy) it seemed, and when I got it upstairs and out of the pillowcase, I saw why. Clearly I’d been blasted out of my mind when I wrapped and taped it: all those layers of newspaper, wound with a whole extra-large roll of heavy-duty, fiber-reinforced packing tape, had seemed like a prudent caution when I was freaked out and high, but back in my room, in the sober light of afternoon, it looked like it had been bound and wrapped by an insane and/or homeless person—mummified, practically: so much tape on it that it wasn’t even quite square any more; even the corners were round. I got the sharpest kitchen knife I could find and sawed at a corner—cautiously at first, worried that the knife would slip in and damage the painting—and then more energetically. But I’d gotten only partway through a three-inch section and my hands were starting to get tired when I heard Xandra coming in downstairs, and I put it back in the pillowcase and taped it to the back of my headboard again until I knew they were going to be gone for a while.

Boris had promised me that we would do two of the leftover hits of acid as soon as his mind got back to usual, which was how he put it; he still felt a bit spaced-out, he confided, saw moving patterns in the fake wood-grain of his desk at school, and the first few times he’d smoked weed he’d started out-and-out tripping again.

“That sounds kind of intense,” I said.

“No, it’s cool. I can make it stop when I want to. I think we should take it at the playground,” he added. “On Thanksgiving holiday maybe.” The abandoned playground was where we’d gone to take E every time but the first, when Xandra came beating on my bedroom door asking us to help her fix the washing machine, which of course we weren’t able to do, but forty-five minutes of standing around with her in the laundry room during the best part of the roll had been a tremendous bringdown.

“Is it going to be a lot stronger than E?”

“No—well, yes, but is wonderful, trust me. I kept wanting Kotku and me to be outside in the air except was too much that close to the highway, lights, cars—maybe this weekend?”

So that was something to look forward to. But just as I was starting to feel good and even hopeful about things again—ESPN hadn’t been on for a week, which was definitely some kind of record—I found my father waiting for me when I got home from school.

“I need to talk to you, Theo,” he said, the moment I walked in. “Do you have a minute?”

I paused. “Well, okay, sure.” The living room looked almost as if it had been burgled—papers scattered everywhere, even the cushions on the sofa slightly out of place.

He stopped pacing—he was moving a bit stiffly, as if his knee hurt him. “Come over here,” he said, in a friendly voice. “Sit down.”

I sat. My dad exhaled; he sat down across from me and ran a hand through his hair.

“The lawyer,” he said, leaning forward with his clasped hands between his knees and meeting my eye frankly.

I waited.

“Your mom’s lawyer. I mean—I know this is short notice, but I really need you to get on the phone with him for me.”

It was windy; outside, blown sand rattled against the glass doors and the patio awning flapped with a sound like a flag snapping. “What?” I said, after a cautious pause. She’d spoken of seeing a lawyer after he left—about a divorce, I figured—but what had come of it, I didn’t know.

“Well—” My dad took a deep breath; he looked at the ceiling. “Here’s the thing. I guess you’ve noticed I haven’t been betting my sports anymore, right? Well,” he said, “I want to quit. While I’m ahead, so to speak. It’s not—” he paused, and seemed to think—“I mean, quite honestly, I’ve gotten pretty good at this stuff by doing my homework and being disciplined about it. I crunch my numbers. I don’t bet impulsively. And, I mean, like I say, I’ve been doing pretty good. I’ve socked away a lot of money these past months. It’s just—”

“Right,” I said uncertainly, in the silence that followed, wondering what he was getting at.

“I mean, why tempt fate? Because—” hand on heart—“I am an alcoholic. I’m the first to admit that. I can’t drink at all. One drink is too many and a thousand’s not enough. Giving up booze was the best thing I ever did. And I mean, with gambling, even with my addictive tendencies and all, it’s always been kind of different, sure I’ve had some scrapes but I’ve never been like some of these guys that, I don’t know, that get so far in that they embezzle money and wreck the family business or whatever. But—” he laughed—“if you don’t want a haircut sooner or later, better stop hanging out at the barber shop right?”

“So?” I said cautiously, after waiting for him to continue.

“So—whew.” My dad ran both hands through his hair; he looked boyish, dazed, incredulous. “Here’s the thing. I’m really wanting to make some big changes right now. Because I have the opportunity to get in on the ground floor of this great business. Buddy of mine has a restaurant. And, I mean, I think it’s going to be a really great thing for all of us—once in a lifetime thing, actually. You know? Xandra’s having such a hard time at work right now with her boss being such a shit and, I don’t know, I just think this is going to be a lot more sane.”

My dad? A restaurant? “Wow—that’s great,” I said. “Wow.”

“Yeah.” My dad nodded. “It’s really great. The thing is, though, to open a place like this—”

“What kind of restaurant?”

My dad yawned, wiped red eyes. “Oh, you know—just simple American food. Steaks and hamburgers and stuff. Just really simple and well prepared. The thing is, though, for my buddy to get the place open and pay his restaurant taxes—”

“Restaurant taxes?”

“Oh God, yes, you wouldn’t believe the kind of fees they’ve got out here. You’ve got to pay your restaurant taxes, your liquor-license taxes, liability insurance—it’s a huge cash outlay to get a place like this up and running.”

“Well.” I could see where he was going with this. “If you need the money in my savings account—”

My dad looked startled. “What?”

“You know. That account you started for me. If you need the money, that’s fine.”

“Oh yeah.” My dad was silent for a moment. “Thanks. I really appreciate that, pal. But actually—” he had stood up, and was walking around—“the thing is, I actually see a really smart way we can do this. Just a short term solution, in order to get the place up and running, you know. We’ll make it back in a few weeks—I mean, a place like this, the location and all, it’s like having a license to print money. It’s just the initial expense. This town is crazy with the taxes and the fees and so forth. I mean—” he laughed, half-apologetically, “you know I wouldn’t ask if it wasn’t an emergency—”

“Sorry?” I said, after a confused pause.

“I mean, like I was saying, I really need you to make this call for me. Here’s the number.” He had it all written out for me on a sheet of paper—a 212 number, I noticed. “You need to telephone this guy and speak to him yourself. His name is Bracegirdle.”

I looked at the paper, and then at my dad. “I don’t understand.”

“You don’t have to understand. All you have to do is say what I tell you.”

“What does it have to do with me?”

“Look, just do it. Tell him who you are, need to have a word, business matter, blah blah blah—”

“But—” Who was this person? “What do you want me to say?”

My father took a long breath; he was taking care to control his expression, something he was fairly good at.

“He’s a lawyer,” he said, on an out breath. “Your mother’s lawyer. He needs to make arrangements to wire this amount of money—” my eyes popped at the sum he was pointing to, $65,000—“into this account” (dragging his finger to the string of numbers beneath it). “Tell him I’ve decided to send you to a private school. He’ll need your name and Social Security number. That’s it.”

“Private school?” I said, after a disoriented pause.

“Well, you see, it’s for tax reasons.”

“I don’t want to go to private school.”

“Wait—wait—just hear me out. As long as these funds are used for your benefit, in the official sense, we’ve got no problem. And the restaurant is for all our benefit, see. Maybe, in the end, yours most of all. And I mean, I could make the call myself, it’s just that if we angle this the right way we’d be saving like thirty thousand dollars that would go to the government otherwise. Hell, I will send you to a private school if you want. Boarding school. I could send you to Andover with all that extra money. I just don’t want half of it to end up with the IRS, know what I’m saying? Also—I mean, the way this thing is set up, by the time you end up going to college, it’s going to end up costing you money, because with that amount of money in there it means you won’t be eligible for a scholarship. The college financial aid people are going to look right at that account and put you in a different income bracket and take 75 percent of it the first year, poof. This way, at least, you’ll get the full use of it, you see? Right now. When it could actually do some good.”

“But—”

“But—” falsetto voice, lolled tongue, goofy stare. “Oh, come on, Theo,” he said, in his normal voice, when I kept on looking at him. “Swear to God, I don’t have time for this. I need you to make this call ASAP, before the offices close back East. If you need to sign something, tell him to FedEx the papers. Or fax them. We just need to get this done as soon as possible, okay?”

“But why do I need to do it?”