Chapter 5

T

HOUGH I HAD DECIDED to leave the suitcase in the package room of my old building, where I felt sure Jose and Goldie would look after it, I grew more and more nervous as the date approached until, at the last minute, I determined to go back for what now seems a fairly dumb reason: in my haste to get the painting out of the apartment, I’d thrown a lot of random things in the bag with it, including most of my summer clothes. So the day before my dad was supposed to pick me up at the Barbours’, I hurried back over to Fifty-Seventh Street with the idea of unzipping the suitcase and taking a couple of the better shirts off the top.Jose wasn’t there, but a new, thick-shouldered guy (Marco V, according to his nametag) stepped in front of me and cut me off with a blocky, obstinate stance less like a doorman’s than a security guard’s. “Sorry, can I help you?” he said.

I explained about the suitcase. But after perusing the log—running a heavy forefinger down the column of dates—he didn’t seem inclined to go in and get it off the shelf for me. “An’ you left this here why?” he said doubtfully, scratching his nose.

“Jose said I could.”

“You got a receipt?”

“No,” I said, after a confused pause.

“Well, I can’t help you. We got no record. Besides, we don’t store packages for non-tenants.”

I’d lived in the building long enough to know that this wasn’t true, but I wasn’t about to argue the point. “Look,” I said, “I used to live here. I know Goldie and Carlos and everybody. I mean—come on,” I said, after a frigid, ill-defined pause, during which I felt his attention drifting. “If you take me back there, I can show you which one.”

“Sorry. Nobody but staff and tenants allowed in back.”

“It’s canvas with ribbon on the handle. My name’s on it, see? Decker?” I was pointing out the label still on our old mailbox for proof when Goldie strolled in from his break.

“Hey! look who’s back! This one’s my kid,” he said to Marco V. “I’ve known him since he was this high. What’s up, Theo my friend?”

“Nothing. I mean—well, I’m leaving town.”

“Oh, yeah? Out to Vegas already?” said Goldie. At his voice, his hand on my shoulder, everything had become easy and comfortable. “Some crazy place to live out there, am I right?”

“I guess so,” I said doubtfully. People kept telling me how crazy things were going to be for me in Vegas although I didn’t understand why, as I was unlikely to be spending much time in casinos or clubs.

“You guess?” Goldie rolled his eyes up and shook his head, with a drollery that my mother in moments of mischief had been apt to imitate. “Oh my God, I’m telling you. That city? The unions they got… I mean, restaurant work, hotel work… very good money, anywhere you look. And the weather? Sun—every day of the year. You’re going to love it out there, my friend. When did you say you’re leaving?”

“Um, today. I mean tomorrow. That’s why I wanted to—”

“Oh, you came for your bag? Hey, sure thing.” Goldie said something sharp-sounding in Spanish to Marco V, who shrugged blandly and headed back into the package room.

“He’s all right, Marco,” said Goldie to me in an undertone. “But, he don’t know anything about your bag here because me and Jose didn’t enter it down in the book, you know what I’m saying?”

I did know what he was saying. All packages had to be logged in and out of the building. By not tagging the suitcase, or entering it into the official record, they had been protecting me from the possibility that somebody else might show up and try to claim it.

“Hey,” I said awkwardly, “thanks for looking out for me…”

“No problemo,” said Goldie. “Hey, thanks, man,” he said loudly to Marco as he took the bag. “Like I said,” he continued in a low voice; I had to walk close beside him in order to hear—“Marco’s a good guy, but we had a lot of tenants complaining because the building was understaffed during the, you know.” He threw me a significant glance. “I mean, like Carlos couldn’t get in to work for his shift that day, I guess it wasn’t his fault, but they fired him.”

“Carlos?” Carlos was the oldest and most reserved of the doormen, like an aging Mexican matinee idol with his pencil moustache and greying temples, his black shoes polished to a high gloss and his white gloves whiter than everyone else’s. “They fired Carlos?”

“I know—unbelievable. Thirty-four years and—” Goldie jerked a thumb over his shoulder—“pfft. And now—management’s all like security-conscious, new staff, new rules, sign everybody in and out and like that—

“Anyway,” he said, as he backed into the front door, pushing it open. “Let me get you a cab, my friend. You’re going straight to the airport?”

“No—” I said, putting out a hand to stop him—I’d been so preoccupied, I hadn’t really noticed what he was doing—but he brushed me aside with a naah motion.

“No, no,” he said—hauling the bag to the curb—“it’s all right, my friend, I got it,” and I realized, in consternation, that he thought I was trying to stop him taking the bag outside because I didn’t have money to tip.

“Hey, wait up,” I said—but at the same instant, Goldie whistled and charged into the street with his hand up. “Here! Taxi!” he shouted.

I stopped in the doorway, dismayed, as the cab swooped in from the curb. “Bingo!” said Goldie, opening the back door. “How’s that for timing?” Before I could quite think how to stop him without looking like a jerk, I was being ushered into the back seat as the suitcase was hoisted into the trunk, and Goldie was slapping the roof, the friendly way he did.

“Have a good trip, amigo,” he said—looking at me, then up at the sky. “Enjoy the sunshine out there for me. You know how I am about the sunshine—I’m a tropical bird, you know? I can’t wait to go home to Puerto Rico and talk to the bees. Hmmn…” he sang, closing his eyes and putting his head to the side. “My sister has a hive of tame bees and I sing them to sleep. Do they got bees in Vegas?”

“I don’t know,” I said, feeling quietly in my pockets to see if I could tell how much money I had.

“Well if you see any bees, tell ’em Goldie says hi. Tell ’em I’m coming.”

“¡Hey! ¡Espera!” It was Jose, hand up—still dressed in his soccer-playing clothes, coming to work straight from his game in the park—swaying towards me with his head-bobbing, athletic walk.

“Hey, manito, you taking off?” he said, leaning down and sticking his head in the window of the cab. “You gotta send us a picture for downstairs!” Down in the basement, where the doormen changed into their uniforms, there was a wall papered with postcards and Polaroids from Miami and Cancun, Puerto Rico and Portugal, which tenants and doormen had sent home to East Fifty-Seventh Street over the years.

“That’s right!” said Goldie. “Send us a picture! Don’t forget!”

“I—” I was going to miss them, but it seemed gay to come out and say so. So all I said was: “Okay. Take it easy.”

“You too,” said Jose, backing away with his hand up. “Stay away from them blackjack tables.”

“Hey, kid,” the cabdriver said, “you want me to take you somewhere or what?”

“Hey, hey, hold your horses, it’s cool,” said Goldie to him. To me he said: “You gonna be fine, Theo.” He gave the cab one last slap. “Good luck, man. See you around. God bless.”

ii.

“DON’T TELL ME,” MY dad said, when he arrived at the Barbours’ the next morning to pick me up in the taxi, “that you’re carrying all that shit on the plane.” For I had another suitcase beside the one with the painting, the one I’d originally planned to take.

“I think you’re going to be over your baggage allowance,” said Xandra a bit hysterically. In the poisonous heat of the sidewalk, I could smell her hair spray even where I was standing. “They only let you carry a certain amount.”

Mrs. Barbour, who had come down to the curb with me, said smoothly: “Oh, he’ll be fine with those two. I go over my limit all the time.”

“Yes, but it costs money.”

“Actually, I think you’ll find it quite reasonable,” said Mrs. Barbour. Though it was early and she was without jewelry or lipstick, somehow even in her sandals and simple cotton dress she still managed to give the impression of being immaculately turned out. “You might have to pay twenty dollars extra at the counter, but that shouldn’t be a problem, should it?”

She and my dad stared each other down like two cats. Then my father looked away. I was a little ashamed of his sports coat, which made me think of guys pictured in the Daily News under suspicion of racketeering.

“You should have told me you had two bags,” he said, sullenly, in the silence (welcome to me) that followed her helpful remark. “I don’t know if all this stuff is going to fit in the trunk.”

Standing at the curb, with the trunk of the cab open, I almost considered leaving the suitcase with Mrs. Barbour and phoning later to tell her what it contained. But before I could make up my mind to say anything, the broad-backed Russian cab driver had taken Xandra’s bag from the trunk and hoisted my second suitcase in, which—with some banging and mashing around—he made to fit.

“See, not very heavy!” he said, slamming the trunk shut, wiping his forehead. “Soft sides!”

“But my carry-on!” said Xandra, looking panicked.

“Not a problem, madame. It can ride in front seat with me. Or in the back with you, if you prefer.”

“All sorted, then,” said Mrs. Barbour—leaning to give me a quick kiss, the first of my visit, a ladies-who-lunch air kiss that smelled of mint and gardenias. “Toodle-oo, you all,” she said. “Have a fantastic trip, won’t you?” Andy and I had said our goodbyes the day before; though I knew he was sad to see me go, still my feelings were hurt that he hadn’t stayed to see me off but instead had gone with the rest of the family up to the supposedly detested house in Maine. As for Mrs. Barbour: she didn’t seem particularly upset to see the last of me, though in truth I felt sick to be leaving.

Her gray eyes, on mine, were clear and cool. “Thank you so much, Mrs. Barbour,” I said. “For everything. Tell Andy I said goodbye.”

“Certainly I will,” she said. “You were an awfully good guest, Theo.” Out in the steamy morning heat haze on Park Avenue, I stood holding her hand for a moment longer—slightly hoping that she would tell me to get in touch with her if I needed anything—but she only said, “Good luck, then,” and gave me another cool little kiss before she pulled away.

iii.

I COULDN’T QUITE FATHOM that I was leaving New York. I’d never been out of the city in my life longer than eight days. On the way to the airport, staring out the window at billboards for strip clubs and personal-injury lawyers that I wasn’t likely to see for a while, a chilling thought settled over me. What about the security check? I hadn’t flown much (only twice, once when I was in kindergarten) and I wasn’t even sure what a security check involved: x-rays? A luggage search?

“Do they open up everything in the airport?” I asked, in a timid voice—and then asked again, because nobody seemed to hear me. I was sitting in the front seat in order to ensure Dad and Xandra’s romantic privacy.

“Oh, sure,” said the cab driver. He was a beefy, big-shouldered Soviet: coarse features, sweaty red-apple cheeks, like a weightlifter gone to fat. “And if they don’t open, they x-ray.”

“Even if I check it?”

“Oh, yes,” he said reassuringly. “They are wiping for explosives, everything. Very safe.”

“But—” I tried to think of some way to formulate what I needed to ask, without betraying myself, and couldn’t.

“Not to worry,” said the driver. “Lots of police at airport. And three-four days ago? Roadblocks.”

“Well, all I can say is, I can’t fucking wait to get out of here,” Xandra said in her husky voice. For a perplexed moment, I thought she was talking to me, but when I looked back, she was turned toward my father.

My dad put his hand on her knee and said something too low for me to hear. He was wearing his tinted glasses, leaning with his head lolled back on the rear seat, and there was something loose and young-sounding in the flatness of his voice, the secret something that passed between them as he squeezed Xandra’s knee. I turned away from them and looked out at the no-man’s-land rushing past: long low buildings, bodegas and body shops, car lots simmering in the morning heat.

“See, I don’t mind sevens in the flight number,” Xandra was saying quietly. “It’s eights freak me out.”

“Yeah, but eight’s a lucky number in China. Take a look at the international board when we get to McCarran. All the incoming flights from Beijing? Eight eight eight.”

“You and your Wisdom of the Chinese.”

“Number pattern. It’s all energy. Meeting of heaven and earth.”

“ ‘Heaven and earth.’ You make it sound like magic.”

“It is.”

“Oh yeah?”

They were whispering. In the rear view mirror, their faces were goofy, and too close together; when I realized they were about to kiss (something that still shocked me, no matter how often I saw them do it), I turned to stare straight ahead. It occurred to me that if I didn’t already know how my mother had died, no power on earth could have convinced me they hadn’t murdered her.

iv.

WHILE WE WERE WAITING to get our boarding passes I was stiff with fear, fully expecting Security to open my suitcase and discover the painting right then, in the check-in line. But the grumpy woman with the shag haircut whose face I still remember (I’d been praying we wouldn’t have to go to her when it was our turn) hoisted my suitcase on the belt with hardly a glance.

As I watched it wobble away, towards personnel and procedures unknown, I felt closed-in and terrified in the bright press of strangers—conspicuous too, as if everyone was staring at me. I hadn’t been in such a dense mob or seen so many cops in one place since the day my mother died. National Guardsmen with rifles stood by the metal detectors, steady in fatigue gear, cold eyes passing over the crowd.

Backpacks, briefcases, shopping bags and strollers, heads bobbing down the terminal as far as I could see. Shuffling through the security line, I heard a shout—of my name, as I thought. I froze.

“Come on, come on,” said my dad, hopping behind me on one foot, trying to get his loafer off, elbowing me in the back, “don’t just stand there, you’re holding up the whole damn line—”

Going through the metal detector, I kept my eyes on the carpet—rigid with fear, expecting any moment a hand to fall on my shoulder. Babies cried. Old people puttered by in motorized carts. What would they do to me? Could I make them understand it wasn’t quite how it looked? I imagined some cinder-block room like in the movies, slammed doors, angry cops in shirtsleeves, forget about it, you’re not going anywhere, kid.

Once out of security, in the echoing corridor, I heard distinct, purposeful steps following close behind me. Again I stopped.

“Don’t tell me,” said my dad—turning back with an exasperated roll of his eyes. “You left something.”

“No,” I said, looking around. “I—” There was no one behind me. Passengers coursed around me on every side.

“Jeez, he’s white as a fucking sheet,” said Xandra. To my father, she said: “Is he all right?”

“Oh, he’ll be fine,” said my father as he started down the corridor again. “Once he’s on the plane. It’s been a tough week for everybody.”

“Hell, if I was him, I’d be freaked about getting on a plane too,” said Xandra bluntly. “After what he’s been through.”

My father—tugging his rolling carry-on behind him, a bag my mother had bought him for his birthday several years before—stopped again.

“Poor kid,” he said—surprising me by his look of sympathy. “You’re not scared, are you?”

“No,” I said, far too fast. The last thing I wanted to do was attract anybody’s attention or look like I was even one quarter as wigged-out as I was.

He knit his brows at me, then turned away. “Xandra?” he said to her, lifting his chin. “Why don’t you give him one of those, you know.”

“Got it,” said Xandra smartly, stopping to fish in her purse, producing two large white bullet-shaped pills. One she dropped in my father’s outstretched palm, and the other she gave to me.

“Thanks,” said my dad, slipping it into the pocket of his jacket. “Let’s go get something to wash these down with, shall we? Put that away,” he said to me as I held the pill up between thumb and forefinger to marvel at how big it was.

“He doesn’t need a whole,” Xandra said, grasping my dad’s arm as she leaned sideways to adjust the strap of her platform sandal.

“Right,” said my dad. He took the pill from me, snapped it expertly in half, and dropped the other half in the pocket of his sports coat as they strolled ahead of me, tugging their luggage behind them.

v.

THE PILL WASN’T STRONG enough to knock me out, but it kept me high and happy and somersaulting in and out of air-conditioned dreams. Passengers whispered in the seats around me as a disembodied air hostess announced the results of the in-flight promotional raffle: dinner and drinks for two at Treasure Island. Her hushed promise sent me down into a dream where I swam deep in greenish-black water, some torchlit competition with Japanese children diving for a pillowcase of pink pearls. Throughout it all the plane roared bright and white and constant like the sea, though at some strange point—wrapped deep in my royal-blue blanket, dreaming somewhere high over the desert—the engines seemed to shut off and go silent and I found myself floating chest upward in zero gravity while still buckled into my chair, which had somehow drifted loose from the other seats to float freely around the cabin.

I fell back into my body with a jolt as the plane hit the runway and bounced, screaming to a stop.

“And… welcome to Lost Wages, Nevada,” the pilot was saying over the intercom. “Our local time in Sin City is 11:47 a.m.”

Half-blind in the glare, plate glass and reflecting surfaces, I trailed after Dad and Xandra through the terminal, stunned by the chatter and flash of slot machines and by the music blaring loud and incongruous so early in the day. The airport was like a mall-sized version of Times Square: towering palms, movie screens with fireworks and gondolas and showgirls and singers and acrobats.

It took a long time for my second bag to come off the carousel. Chewing my fingernails, I stared fixedly at a billboard of a grinning Komodo dragon, an ad for some casino attraction: “Over 2,000 reptiles await you.” The baggage-claim crowd was like a group of colorful stragglers in front of some third-rate nightclub: sunburns, disco shirts, tiny bejeweled Asian ladies with giant logo sunglasses. The belt was circling around mostly empty and my dad (itching for a cigarette, I could tell) was starting to stretch and pace and rub his knuckles against his cheek like he did when he wanted a drink when there it came, the last one, khaki canvas with the red label and the multicolored ribbon my mother had tied around the handle.

My dad, in one long step, lunged forward and grabbed it before I could get to it. “About time,” he said jauntily, tossing it onto the baggage cart. “Come on, let’s get the hell out of here.”

Out we rolled through the automatic doors and into a wall of breathtaking heat. Miles of parked cars stretched around us in all directions, hooded and still. Rigidly I stared straight ahead—chrome knives glinting, horizon shimmering like wavy glass—as if looking back, or hesitating, might invite some uniformed party to step in front of us. Yet no one collared me or shouted at us to stop. No one even looked at us.

I was so disoriented in the glare that when my dad stopped in front of a new silver Lexus and said: “Okay, this is us,” I tripped and nearly fell on the curb.

“This is yours?” I said, looking between them.

“What?” said Xandra coquettishly, clumping around to the passenger side in her high shoes as my dad beeped the lock open. “You don’t like it?”

A Lexus? Every day, I was struck by all sorts of matters large and small that I urgently needed to tell my mother and as I stood dumbly watching my dad hoist the bags in the trunk my first thought was: wow, wait until she hears about this. No wonder he hadn’t sent money home.

My dad threw aside his half-smoked Viceroy with a flourish. “Okay,” he said, “hop in.” The desert air had magnetized him. Back in New York, he had looked a bit worn-out and seedy but out in the rippling heat his white sportcoat and his cult-leader sunglasses made sense.

The car—which started with the push of a button—was so quiet that at first I didn’t realize we were moving. Away we glided, into depthlessness and space. Accustomed as I was to jolting around in the backs of taxis, the smoothness and chill of the ride was sealed off, eerie: brown sand, vicious glare, trance and silence, blown trash whipping at the chain-link fence. I still felt numbed and weightless from the pill, and the crazy façades and superstructures of the Strip, the violent shimmer where the dunes met sky, made me feel as if we had touched down on another planet.

Xandra and my dad had been talking quietly in the front seat. Now she turned to me—snapping gum, robust and sunny, her jewelry blazing in the strong light. “So, whaddaya think?” she said, exhaling a strong breath of Juicy Fruit.

“It’s wild,” I said—watching a pyramid sail past my window, the Eiffel Tower, too overwhelmed to take it in.

“You think it’s wild now?” said my dad, tapping his fingernail on the steering wheel in a manner I associated with frayed nerves and late-night quarrels after he got home from the office. “Just wait until you see it lit up at night.”

“See there—check it out,” said Xandra, reaching over to point out the window on my dad’s side. “There’s the volcano. It really works.”

“Actually, I think they’re renovating it. But in theory, yeah. Hot lava. On the hour, every hour.”

“Exit to the left in point two miles,” said a woman’s computerized voice.

Carnival colors, giant clown heads and XXX signs: the strangeness exhilarated me, and also frightened me a little. In New York, everything reminded me of my mother—every taxi, every street corner, every cloud that passed over the sun—but out in this hot mineral emptiness, it was as if she had never existed; I could not even imagine her spirit looking down on me. All trace of her seemed burned away in the thin desert air.

As we drove, the improbable skyline dwindled into a wilderness of parking lots and outlet malls, loop after faceless loop of shopping plazas, Circuit City, Toys “R” Us, supermarkets and drugstores, Open Twenty-Four Hours, no saying where it ended or began. The sky was wide and trackless, like the sky over the sea. As I fought to stay awake—blinking against the glare—I was ruminating in a dazed way over the expensive-smelling leather interior of the car and thinking of a story I’d often heard my mother tell: of how, when she and my dad were dating, he’d turned up in a Porsche he’d borrowed from a friend to impress her. Only after they were married had she learned that the car wasn’t really his. She’d seemed to think this was funny—although given other, less amusing facts that came to light after their marriage (such as his arrest record, as a juvenile, on charges unknown), I wondered that she was able to find anything very entertaining about the story.

“Um, you’ve had this car how long?” I said, speaking up over their conversation in front.

“Oh—gosh—little over a year now, isn’t that right, Xan?”

A year? I was still chewing this over—this figure meant my dad had acquired the car (and Xandra) before he’d disappeared—when I looked up and saw that the strip malls had given way to an endless-seeming grid of small stucco homes. Despite the air of boxed, bleached sameness—row on row, like stones in a cemetery—some of the houses were painted in festive pastels (mint green, rancho pink, milky desert blue) and there was something excitingly foreign about the sharp shadows, the spiked desert plants. Having grown up in the city, where there was never enough space, I was if anything pleasantly surprised. It would be something new to live in a house with a yard, even if the yard was only brown rocks and cactus.

“Is this still Las Vegas?” As a game, I was trying to pick out what made the houses different from each other: an arched doorway here, a swimming pool or a palm tree there.

“You’re seeing a whole different part now,” my dad said—exhaling sharply, stubbing out his third Viceroy. “This is what tourists never see.”

Though we’d been driving a while, there were no landmarks, and it was impossible to say where we were going or in which direction. The skyline was monotonous and unchanging and I was fearful that we might drive through the pastel houses altogether and out into the alkali waste beyond, into some sun-beaten trailer park from the movies. But instead—to my surprise—the houses began to grow larger: with second stories, with cactus gardens, with fences and pools and multi-car garages.

“Okay, this is us,” said my dad, turning into a road that had an imposing granite sign with copper letters: The Ranches at Canyon Shadows.

“You live here?” I said, impressed. “Is there a canyon?”

“No, that’s just the name of it,” said Xandra.

“See, they have a bunch of different developments out here,” said my dad, pinching the bridge of his nose. I could tell by his tone—his scratchy old needing-a-drink voice—that he was tired and not in a very good mood.

“Ranch communities is what they call them,” said Xandra.

“Right. Whatever. Oh, shut the fuck up,” snapped my dad, reaching over to turn the volume down as the lady on the navigation system piped up with instructions again.

“They all have different themes, sort of,” said Xandra, who was dabbing on lip gloss with the pad of her little finger. “There’s Pueblo Breeze, Ghost Ridge, Dancing Deer Villas. Spirit Flag is the golf community? And Encantada is the fanciest, lots of investment properties—Hey, turn here, sweet pea,” she said, clutching his arm.

My dad kept driving straight and did not answer.

“Shit!” Xandra turned in her seat to look at the road receding behind us. “Why do you always have to go the long way?”

“Don’t start with the shortcuts. You’re as bad as the Lexus lady.”

“Yeah, but it’s faster. By fifteen minutes. Now we’re going to have to drive all the way around Dancing Deer.”

My dad blew out an exasperated breath. “Look—”

“What’s so hard about cutting over to Gitana Trails and making two lefts and a right? Because that’s all it is. If you get off on Desatoya—”

“Look. You want to drive the car? Or you want to let me drive the fucking car?”

I knew better than to challenge my dad when he took that tone, and apparently Xandra did too. She flounced around in her seat and—in a deliberate manner that seemed calculated to annoy him—turned up the radio very loud and started punching through static and commercials.

The stereo was so powerful I could feel it thumping through the back of my white leather seat. Vacation, all I ever wanted… Light climbed and burst through the wild desert clouds—never-ending sky, acid blue, like a computer game or a test pilot’s hallucination.

“Vegas 99, serving up the Eighties and Nineties,” said the fast, excited voice on the radio. “And here’s Pat Benatar coming up for you, in our Ladies of the Eighties Lapdance lunch.”

In Desatoya Ranch Estates, on 6219 Desert End Road, where lumber was stacked in some of the yards and sand blew in the streets, we turned into the driveway of a large Spanish-looking house, or maybe it was Moorish, shuttered beige stucco with arched gables and a clay-tiled roof pitched at various startling angles. I was impressed by the aimlessness and sprawl of it, its cornices and columns, the elaborate ironwork door with its sense of a stage set, like a house from one of the Telemundo soap operas the doormen always had going in the package room.

We got out of the car and were circling around to the garage entrance with our suitcases when I heard an eerie, distressing noise: screaming, or crying, from inside the house.

“Gosh, what’s that?” I said, dropping my bags, unnerved.

Xandra was leaning sideways, stumbling a bit in her high shoes and grappling for her key. “Oh, shut up, shut up, shutthefuckup,” she was muttering under her breath. Before she’d opened the door all the way, a hysterical stringy mop shot out, shrieking, and began to hop and dance and caper all around us.

“Get down!” Xandra was yelling. Through the half-opened door, safari music (trumpeting elephants, chattering monkeys) was playing so loud that I could hear it all the way out in the garage.

“Wow,” I said, peering inside. The air inside smelled hot and stale: old cigarette smoke, new carpet, and—no question about it—dog shit.

“For the zookeeper, big cats pose a unique series of challenges,” the voice on the television boomed. “Why don’t we follow Andrea and her staff on their morning rounds.”

“Hey,” I said, stopping in the door with my bag, “you left the television on.”

“Yes,” said Xandra—brushing past me—“that’s Animal Planet, I left it on for him. For Popper. I said get down!” she snapped at the dog, who was scrabbling at her knees with his claws as she hobbled in on her platforms and switched the television off.

“He stayed by himself?” I said, over the dog’s shrieks. He was one of those long-haired girly dogs who would have been white and fluffy if he was clean.

“Oh, he’s got a drinking fountain from Petco,” said Xandra, wiping her forehead with the back of her hand as she stepped over the dog. “And one of those big feeder things?”

“What kind is he?”

“Maltese. Pure bred. I won him in a raffle. I mean, I know he needs a bath, it’s a pain to keep them groomed. That’s right, just look what you did to my pants,” she said to the dog. “White jeans.”

We were standing in a large, open room with high ceilings and a staircase that ran up to a sort of railed mezzanine on one side—a room almost as big as the entire apartment I’d grown up in. But when my eyes adjusted from the bright sun, I was taken aback by how bare it was. Bone-white walls. Stone fireplace, with sort of a fake hunting-lodge feel. Sofa like something from a hospital waiting room. Across from the glass patio doors stretched a wall of built-in shelves, mostly empty.

My dad creaked in, and dropped the suitcases on the carpet. “Jesus, Xan, it smells like shit in here.”

Xandra—leaning over to set down her purse—winced as the dog began to jump and climb and claw all over her. “Well, Janet was supposed to come and let him out,” she said over his high-pitched screams. “She had the key and everything. God, Popper,” she said, wrinkling her nose, turning her head away, “you stink.”

The emptiness of the place stunned me. Until that moment, I had never questioned the necessity of selling my mother’s books and rugs and antiques, or the need of sending almost everything else to Goodwill or the garbage. I had grown up in a four-room apartment where closets were packed to overflowing, where every bed had boxes beneath it and pots and pans were hung from the ceiling because there wasn’t room in the cupboards. But—how easy it would have been to bring some of her things, like the silver box that had been her mother’s, or the painting of a chestnut mare that looked like a Stubbs, or even her childhood copy of Black Beauty! It wasn’t as if he couldn’t have used a few good pictures or some of the furniture she’d inherited from her parents. He had gotten rid of her things because he hated her.

“Jesus Christ,” my father was saying, his voice raised angrily over the shrill barks. “This dog has destroyed the place. Quite honestly.”

“Well, I don’t know—I mean, I know it’s a mess but Janet said—”

“I told you, you should have kennelled this dog. Or, I don’t know, taken him to the pound. I don’t like having him in the house. Outdoors is the place for him. Didn’t I tell you this was going to be a problem? Janet is such a fucking flake—”

“So he went on the rug a few times? So what? And—what the hell are you looking at?” said Xandra angrily, stepping over the shrieking dog—and with a bit of a start, I realized it was me she was glaring at.

vi.

MY NEW ROOM FELT so bare and lonely that, after I unpacked my bags, I left the sliding door of the closet open so I could see my clothes hanging inside. From downstairs, I could still hear Dad shouting about the carpet. Unfortunately, Xandra was shouting too, getting him more wound up, which (I could have told her, if she’d asked) was exactly the wrong way to handle him. At home, my mother had known how to suffocate my dad’s anger by growing silent, a low, unwavering flame of contempt that sucked all the oxygen out of the room and made everything he said and did seem ridiculous. Eventually he would whoosh out with a thunderous slam of the front door and when he returned—hours later, with a quiet click of the key in the lock—he would walk around the apartment as if nothing had happened: going to the refrigerator for a beer, asking in a perfectly normal voice where his mail was.

Of the three empty rooms upstairs I’d chosen the largest, which like a hotel room had its own tiny bathroom to the side. Floor heavily carpeted in steel blue plush. Bare mattress, with a plastic package of bedsheets at the foot. Legends Percale. Twenty percent off. A gentle mechanical hum emanated from the walls, like the hum of an aquarium filter. It seemed like the kind of room where a call girl or a stewardess would be murdered on television.

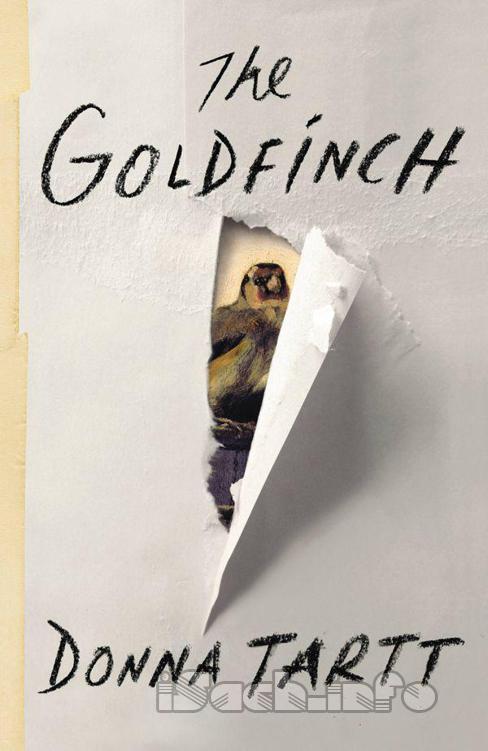

With an ear out for Dad and Xandra, I sat on the mattress with the wrapped painting on my knees. Even with the door locked, I was hesitant to take the paper off in case they came upstairs, and yet the desire to look at it was irresistible. Carefully, carefully, I scratched the tape with my thumbnail and peeled it up by the edges.

The painting slid out more easily than I’d expected, and I found myself biting back a gasp of pleasure. It was the first time I’d seen the painting in the light of day. In the arid room—all sheetrock and whiteness—the muted colors bloomed with life; and even though the surface of the painting was ghosted ever so slightly with dust, the atmosphere it breathed was like the light-rinsed airiness of a wall opposite an open window. Was this why people like Mrs. Swanson went on about the desert light? She had loved to warble on about what she called her “sojourn” in New Mexico—wide horizons, empty skies, spiritual clarity. Yet as if by some trick of the light the painting seemed transfigured, as the dark roofline view of water tanks from my mother’s bedroom window sometimes stood gilded and electrified for a few strange moments in the stormlight of late afternoon, right before a summer cloudburst.

“Theo?” My dad, knocking briskly at the door. “You hungry?”

I stood up, hoping he wouldn’t try the door and find it locked. My new room was as bare as a jail cell; but the closet had high shelves, well above my dad’s eye level, very deep.

“I’m going to pick up some Chinese. Want me to get you something?”

Would my dad know what the painting was, if he saw it? I hadn’t thought so—but looking at it in the light, the glow it threw off, I realized that any fool would. “Um, be right there,” I called, my voice false-sounding and hoarse, slipping the painting into an extra pillowcase and hiding it under the bed before hurrying out of the room.

vii.

IN THE WEEKS IN Las Vegas before school started, loitering around downstairs with the earphones of my iPod in but the sound off, I learned a number of interesting facts. For starters: my dad’s former job had not involved nearly as much business travel to Chicago and Phoenix as he had led us to believe. Unbeknownst to my mother and me, he had actually been flying out to Vegas for some months, and it was in Vegas—in an Asian-themed bar at the Bellagio—that he and Xandra had met. They had been seeing each other for a while before my dad vanished—a bit over a year, as I gathered; it seemed that they had celebrated their “anniversary” not long before my mother died, with dinner at Delmonico Steakhouse and the Jon Bon Jovi concert at the MGM Grand. (Bon Jovi! Of all the many things I was dying to tell my mother—and there were thousands of them, if not millions—it seemed terrible that she would never know this hilarious fact.)

Another thing I figured out, after a few days in the house on Desert End Road: what Xandra and my dad really meant when they said my dad had “stopped drinking” was that he’d switched from Scotch (his beverage of choice) to Corona Lights and Vicodin. I had been puzzled by how frequently the peace sign, or V for Victory, was flashed between them, in all sorts of incongruous contexts, and it might have gone on being a mystery for a lot longer if my dad hadn’t just come out and asked Xandra for a Vicodin when he thought I wasn’t listening.

I didn’t know anything about Vicodin except that it was something that a wild movie actress I liked was always getting her picture in the tabloids about: stumbling from her Mercedes as police lights flashed in the background. Several days later, I came across a plastic bag with what looked like about three hundred pills in it—sitting on the kitchen counter, alongside a bottle of my dad’s Propecia and a stack of unpaid bills—which Xandra snatched up and threw in her purse.

“What are those?” I said.

“Um, vitamins.”

“Why are they in that baggie like that?”

“I get them from this bodybuilder guy at work.”

The weird thing was—and this was something else I wished I could have discussed with my mother—the new, drugged-out Dad was a much more pleasant and predictable companion than the Dad of old. When my father drank, he was a twist of nerves—all inappropriate jokes and aggressive bursts of energy, right up until the moment he passed out—but when he stopped drinking, he was worse. He blasted along ten paces ahead of my mother and me on the sidewalk, talking to himself and patting his suit pockets as if for a weapon. He brought home stuff we didn’t want and couldn’t afford, like crocodile Manolos for my mother (who hated high heels) and not even in the right size. He lugged piles of paper home from the office and sat up past midnight drinking iced coffee and punching in numbers on the calculator, sweat pouring off him like he’d just done forty minutes on the StairMaster. Or else he would make a big deal of going to some party way the hell over in Brooklyn (“What do you mean, ‘maybe I shouldn’t go’? You think I should live like a fucking hermit, is that it?”) and then—after dragging my mother there—storm out ten minutes later after insulting someone or mocking them to their face.

This was a different, more affable energy, with the pills: a combination of sluggishness and brightness, a bemused, goofy, floating quality. His walk was looser. He napped more, nodded agreeably, lost the thread of his arguments, ambled about barefoot with his bathrobe halfway open. From his genial cursing, his infrequent shaving, the relaxed way he talked around the cigarette in the corner of his mouth, it was almost as if he were playing a character: some cool guy from a fifties noir or maybe Ocean’s Eleven, a lazy, sated gangster with not much to lose. Yet even in the midst of his new laid-backness he still had that crazed and slightly heroic look of schoolboy insolence, all the more stirring since it was drifting towards autumn, half-ruined and careless of itself.

In the house on Desert End Road, which had the super-expensive cable television package my mother would never let us get, he drew the blinds against the glare and sat smoking in front of the television, glassy as an opium addict, watching ESPN with the sound off, no sport in particular, anything and everything that came on: cricket, jai alai, badminton, croquet. The air was overly chilled, with a stale, refrigerated smell; sitting motionless for hours, the filament of smoke from his Viceroy floating to the ceiling like a thread of incense, he might as well have been contemplating the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha as the leaderboard at the PGA or whatever.

What wasn’t clear was if my dad had a job—or, if he did, what kind of job it was. The phone rang all hours of the day and night. My dad went in the hallway with the handset, his back to me, bracing his arm against the wall and staring at the carpet as he talked, something in his posture suggesting the attitude of a coach at the end of a tough game. Usually he kept his voice well down but even when he didn’t, it was tough to understand his end of the conversation: vig, moneyline, odds-on favorite, straight up and against the spread. He was gone much of the time, on unexplained errands, and a lot of nights he and Xandra didn’t come home at all. “We get comped a lot at the MGM Grand,” he explained, rubbing his eyes, sinking back into the sofa cushions with an exhausted sigh—and again I got a sense of the character he was playing, moody playboy, relic of the eighties, easily bored. “I hope you don’t mind. It’s just when she’s working the late shift, it’s easier for us to crash on the Strip.”

viii.

“WHAT ARE ALL THESE papers everywhere?” I asked Xandra one day while she was in the kitchen making her white diet drink. I was confused by the pre-printed cards I kept finding all over the house: grids pencilled in with row after monotonous row of figures. Vaguely scientific-looking, they had a creepy feel of DNA sequences, or maybe spy transmissions in binary code.

She switched the blender off, flicked the hair out of her eyes. “Excuse me?”

“These work sheets or whatever.”

“Bacca-rat!” said Xandra—rolling the r, doing a tricky little fillip with her fingers.

“Oh,” I said after a flat pause, though I’d never heard the word before.

She stuck her finger in the drink, and licked it off. “We go to the baccarat salon at the MGM Grand a lot?” she said. “Your dad likes to keep track of his played games.”

“Can I go some time?”

“No. Well yeah—I guess you could,” she said, as if I’d inquired about vacation prospects in some unstable Islamic nation. “Except they’re not super-welcoming of kids in the casinos? You’re not really allowed to come and watch us play.”

So what, I thought. Standing around and watching Dad and Xandra gamble was scarcely my idea of fun. Aloud, I said: “But I thought they had tigers and pirate boats and things like that.”

“Yeah, well. I guess.” She was reaching up for a glass on the shelf, exposing a quadrangle of blue-inked Chinese characters between her T-shirt and her low-slung jeans. “They tried to sell this whole family-friendly package a few years ago, but it didn’t wash.”

ix.

I MIGHT HAVE LIKED Xandra in other circumstances—which, I guess, is sort of like saying I might have liked the kid who beat me up if he hadn’t beat me up. She was my first inkling that women over forty—women maybe not all that great-looking to start with—could be sexy. Though she wasn’t pretty in the face (bullet eyes, blunt little nose, tiny teeth) still she was in shape, she worked out, and her arms and legs were so glossy and tan that they looked almost sprayed, as if she anointed herself with lots of creams and oils. Teetering in her high shoes, she walked fast, always tugging at her too-short skirt, a forward-leaning walk, weirdly alluring. On some level, I was repelled by her—by her stuttery voice, her thick, shiny lip gloss that came in a tube that said Lip Glass; by the multiple pierce holes in her ears and the gap in her front teeth that she liked to worry with her tongue—but there was something sultry and exciting and tough about her too: an animal strength, a purring, prowling quality when she was out of her heels and walking barefoot.

Vanilla Coke, vanilla Chapstick, vanilla diet drink, Stoli Vanilla. Off from work, she dressed like sort of a rapped-up tennis mom, short white skirts, lots of gold jewelry. Even her tennis shoes were new and spanking white. Sunbathing by the pool, she wore a white crocheted bikini; her back was wide but thin, lots of ribs, like a man without his shirt on. “Uh-oh, wardrobe malfunction,” she said when she sat up from the lounge chair without remembering to fasten her top, and I saw that her breasts were as tan as the rest of her.

She liked reality shows: Survivor, American Idol. She liked to shop at Intermix and Juicy Couture. She liked to call her friend Courtney and “vent,” and a lot of her venting, unfortunately, was on the subject of me. “Can you believe it?” I heard her saying on the telephone when my dad was out of the house one day. “I didn’t sign on for this. A kid? Hello?

“Yeah, it’s a pain in the ass, all right,” she continued, inhaling lazily on her Marlboro Light—pausing by the glass doors that led to the pool, staring down at her freshly painted, honeydew-green toenails. “No,” she said after a brief pause. “I don’t know how long for. I mean, what does he expect me to think? I’m not a freaking soccer mom.”

Her complaints seemed routine, not particularly heated or personal. Still it was hard to know just how to make her like me. Previously, I had operated on the assumption that mom-aged women loved it when you stood around and tried to talk to them but with Xandra I soon learned that it was better not to joke around or inquire too much about her day when she came home in a bad mood. Sometimes, when it was just the two of us, she switched the channel from ESPN and we sat eating fruit cocktail and watching movies on Lifetime peacefully enough. But when she was annoyed with me, she had a cold way of saying “Apparently” in answer to almost anything I said, making me feel stupid.

“Um, I can’t find the can opener.”

“Apparently.”

“There’s going to be a lunar eclipse tonight.”

“Apparently.”

“Look, sparks are coming out of the wall socket.”

“Apparently.”

Xandra worked nights. Usually she breezed off around three thirty in the afternoon, dressed in her curvy work uniform: black jacket, black pants made of some stretchy, tight-fitting material, with her blouse unbuttoned to her freckled breastbone. The nametag pinned to her blazer said XANDRA in big letters and underneath: Florida. In New York, when we’d been out at dinner that night, she’d told me that she was trying to break into real estate but what she really did, I soon learned, was manage a bar called “Nickels” in a casino on the Strip. Sometimes she came home with plastic platters of bar snacks wrapped in cellophane, things like meatballs and chicken teriyaki bites, which she and my dad carried in front of the television and ate with the sound off.

Living with them was like living with roommates I didn’t particularly get along with. When they were at home, I stayed in my room with the door shut. And when they were gone—which was most of the time—I prowled through the farther reaches of the house, trying to get used to its openness. Many of the rooms were bare of furniture, or almost bare, and the open space, the uncurtained brightness—all exposed carpet and parallel planes—made me feel slightly unmoored.

And yet it was a relief not to feel constantly exposed, or onstage, the way I had at the Barbours’. The sky was a rich, mindless, never-ending blue, like a promise of some ridiculous glory that wasn’t really there. No one cared that I never changed my clothes and wasn’t in therapy. I was free to goof off, lie in bed all morning, watch five Robert Mitchum movies in a row if I felt like it.

Dad and Xandra kept their bedroom door locked—which was too bad, as that was the room where Xandra kept her laptop, off-limits to me unless she was home and she brought it down for me to use in the living room. Poking around when they were out of the house, I found real estate leaflets, new wineglasses still in the box, a stack of old TV Guides, a cardboard box of beat-up trade paperbacks: Your Moon Signs, The South Beach Diet, Caro’s Book of Poker Tells, Lovers and Players by Jackie Collins.

The houses around us were empty—no neighbors. Five or six houses down, on the opposite side of the street, there was an old Pontiac parked out front. It belonged to a tired-looking woman with big boobs and ratty hair whom I sometimes saw standing barefoot out in front of her house in the late afternoon, clutching a pack of cigarettes and talking on her cell phone. I thought of her as “the Playa” as the first time I’d seen her, she’d been wearing a T-shirt that said DON’T HATE THE PLAYA, HATE THE GAME. Apart from her, the Playa, the only other living person I’d seen on our street was a big-bellied man in a black sports shirt way the hell down at the cul-de-sac, wheeling a garbage can out to the curb (although I could have told him: no garbage pickup on our street. When it was time to take the trash out, Xandra made me sneak out with the bag and throw it in the dumpster of the abandoned-under-construction house a few doors down). At night—apart from our house, and the Playa’s—complete darkness reigned on the street. It was all as isolated as a book we’d read in the third grade about pioneer children on the Nebraska prairie, except with no siblings or friendly farm animals or Ma and Pa.

The hardest thing, by far, was being stuck in the middle of nowhere—no movie theaters or libraries, not even a corner store. “Isn’t there a bus or something?” I asked Xandra one evening when she was in the kitchen unwrapping the night’s plastic tray of Atomic Wings and blue cheese dip.

“Bus?” said Xandra, licking a smear of barbecue sauce off her finger.

“Don’t you have public transportation out here?”

“Nope.”

“What do people do?”

Xandra cocked her head to the side. “They drive?” she said, as if I was a retard who’d never heard of cars.

One thing: there was a pool. My first day I’d burned myself brick red within an hour and suffered a sleepless night on scratchy new sheets. After that, I only went out after the sun started going down. The twilights out there were florid and melodramatic, great sweeps of orange and crimson and Lawrence-in-the-desert vermilion, then night dropping dark and hard like a slammed door. Xandra’s dog Popper—who lived, for the most part, in a brown plastic igloo on the shady side of the fence—ran back and forth along the side of the pool yapping as I floated on my back, trying to pick out constellations I knew in the confusing white spatter of stars: Lyra, Cassiopeia the queen, whiplash Scorpius with the twin stings in his tail, all the friendly childhood patterns that had twinkled me to sleep from the glow-in-the-dark planetarium stars on my bedroom ceiling back in New York. Now, transfigured—cold and glorious like deities with their disguises flung off—it was as if they’d flown through the roof and into the sky to assume their true, celestial homes.

x.

MY SCHOOL STARTED THE second week of August. From a distance, the fenced complex of long, low, sand-colored buildings, connected by roofed walkways, made me think of a minimum security prison. But once I stepped through the doors, the brightly colored posters and the echoing hallway were like falling back into a familiar old dream of school: crowded stairwells, humming lights, biology classroom with an iguana in a piano-sized tank; locker-lined hallways that were familiar like a set from some much-watched television show—and though the resemblance to my old school was only superficial, on some strange wavelength it was also comforting and real.

The other section of Honors English was reading Great Expectations. Mine was reading Walden; and I hid myself in the coolness and silence of the book, a refuge from the sheet-metal glare of the desert. During the morning break (where we were rounded up and made to go outside, in a chain-fenced yard near the vending machines), I stood in the shadiest corner I could find with my mass-market paperback and, with a red pencil, went through and underlined a lot of particularly bracing sentences: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” “A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind.” What would Thoreau have made of Las Vegas: its lights and rackets, its trash and daydreams, its projections and hollow façades?

At my school, the sense of transience was unsettling. There were a lot of army brats, a lot of foreigners—many of them the children of executives who had come to Las Vegas for big managerial and construction jobs. Some of them had lived in nine or ten different states in as many years, and many of them had lived abroad: in Sydney, Caracas, Beijing, Dubai, Taipei. There were also a good many shy, half-invisible boys and girls whose parents had fled rural hardship for jobs as hotel busboys and chambermaids. In this new ecosystem money, or even good looks, did not seem to determine popularity; what mattered most, as I came to realize, was who’d lived in Vegas the longest, which was why the knock-down Mexican beauties and itinerant construction heirs sat alone at lunch while the bland, middling children of local realtors and car dealers were the cheerleaders and class presidents, the unchallenged elite of the school.

The days were clear and beautiful; and, as September rolled around, the hateful glare gave way to a certain luminosity, a dusty, golden quality. Sometimes I ate lunch at the Spanish Table, to practice my Spanish; sometimes I ate lunch at the German Table even though I didn’t speak German because several of the German II kids—children of Deutsche Bank and Lufthansa executives—had grown up in New York. Of my classes, English was the only one I looked forward to, yet I was disturbed by how many of my classmates disliked Thoreau, railed against him even, as if he (who claimed never to have learned anything of value from an old person) was an enemy and not a friend. His scorn of commerce—invigorating to me—nettled a lot of the more vocal kids in Honors English. “Yeah, right,” shouted an obnoxious boy whose hair was gelled and combed stiff like a Dragon Ball Z character—“some kind of world it would be if everybody just dropped out and moped around in the woods—”

“Me, me, me,” whined a voice in the back.

“It’s antisocial,” a loudmouth girl interjected eagerly over the laughter that followed this—shifting in her seat, turning back to the teacher (a limp, long-boned woman named Mrs. Spear, who always wore brown sandals and earthtone colors, and looked as if she was suffering from major depression). “Thoreau is always just sitting around on his can telling us how good he has it—”

“—Because,” said the Dragon Ball Z boy—his voice rising gleefully, “if everybody dropped out, like he’s saying to do? What kind of community would we have, if it was just people like him? We wouldn’t have hospitals and stuff. We wouldn’t have roads.”

“Twat,” mumbled a welcome voice—just loud enough for everybody around to hear.

I turned to see who had said this: the burnout-looking boy across the aisle, slouched and drumming his desk with his fingers. When he saw me looking at him, he raised a surprisingly lively eyebrow, as if to say: can you believe these fucking idiots?

“Did someone have something to say back there?” said Mrs. Spear.

“Like Thoreau gave a toss about roads,” said the burnout boy. His accent took me by surprise: foreign, I couldn’t place it.

“Thoreau was the first environmentalist,” said Mrs. Spear.

“He was also the first vegetarian,” said a girl in back.

“Figures,” said someone else. “Mr. Crunchy-chewy.”

“You’re all totally missing my point,” the Dragon Ball Z boy said excitedly. “Somebody has to build roads and not just sit in the woods looking at ants and mosquitoes all day. It’s called civilization.”

My neighbor let out a sharp, contemptuous bark of a laugh. He was pale and thin, not very clean, with lank dark hair falling in his eyes and the unwholesome wanness of a runaway, callused hands and black-circled nails chewed to the nub—not like the shiny-haired, ski-tanned skate rats from my school on the Upper West Side, punks whose dads were CEOs and Park Avenue surgeons, but a kid who might conceivably be sitting on a sidewalk somewhere with a stray dog on a rope.

“Well, to address some of these questions? I’d like for everybody to turn back to page fifteen,” Mrs. Spear said. “Where Thoreau is talking about his experiment in living.”

“Experiment how?” said Dragon Ball Z. “Why is living in the woods like he does any different from a caveman?”

The dark-haired boy scowled and sank deeper in his seat. He reminded me of the homeless-looking kids who stood around passing cigarettes back and forth on St. Mark’s Place, comparing scars, begging for change—same torn-up clothes and scrawny white arms; same black leather bracelets tangled at the wrists. Their multi-layered complexity was a sign I couldn’t read, though the general import was clear enough: different tribe, forget about it, I’m way too cool for you, don’t even try to talk to me. Such was my mistaken first impression of the only friend I made when I was in Vegas, and—as it turned out—one of the great friends of my life.

His name was Boris. Somehow we found ourselves standing together in the crowd that was waiting for the bus after school that day.

“Hah. Harry Potter,” he said, as he looked me over.

“Fuck you,” I said listlessly. It was not the first time, in Vegas, I’d heard the Harry Potter comment. My New York clothes—khakis, white oxford shirts, the tortoiseshell glasses which I unfortunately needed to see—made me look like a freak at a school where most people dressed in tank tops and flip flops.

“Where’s your broomstick?”

“Left it at Hogwarts,” I said. “What about you? Where’s your board?”

“Eh?” he said, leaning in to me and cupping his hand behind his ear with an old-mannish, deaf-looking gesture. He was half a head taller than me; along with jungle boots and bizarre old fatigues with the knees busted out, he was wearing a ratted-up black T-shirt with a snowboarding logo, Never Summer in white gothic letters.

“Your shirt,” I said, with a curt nod. “Not much boarding in the desert.”

“Nyah,” said Boris, pushing the stringy dark hair out of his eyes. “I don’t know how to snowboard. I just hate the sun.”

We ended up together on the bus, in the seat closest to the door—clearly an unpopular place to sit, judging from the urgent way other kids muscled and pushed to the rear, but I hadn’t grown up riding a school bus and apparently neither had he, as he too seemed to think it only natural to fling himself down in the first empty seat up front. For a while we didn’t say much, but it was a long ride and eventually we got talking. It turned out that he lived in Canyon Shadows too—but farther out, the end that was getting reclaimed by the desert, where a lot of the houses weren’t finished and sand stood in the streets.

“How long have you been here?” I asked him. It was the question all the kids asked each other at my new school, like we were doing jail time.

“Dunno. Two months maybe?” Though he spoke English fluently enough, with a strong Australian accent, there was also a dark, slurry undercurrent of something else: a whiff of Count Dracula, or maybe it was KGB agent. “Where are you from?”

“New York,” I said—and was gratified at his silent double-take, his lowered eyebrows that said: very cool. “What about you?”

He pulled a face. “Well, let’s see,” he said, slumping back in his seat and counting off the countries on his fingers. “I’ve lived in Russia, Scotland which was maybe cool but I don’t remember it, Australia, Poland, New Zealand, Texas for two months, Alaska, New Guinea, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Ukraine—”

“Jesus Christ.”

He shrugged. “Mostly Australia, Russia, and Ukraine, though. Those three places.”

“Do you speak Russian?”

He made a gesture that I took to mean more or less. “Ukrainian too, and Polish. Though I’ve forgotten a lot. The other day, I tried to remember what was the word for ‘dragonfly’ and couldn’t.”

“Say something.”

He obliged, something spitty and guttural.

“What does that mean?”

He chortled. “It means ‘Fuck you up the ass.’ ”

“Yeah? In Russian?”

He laughed, exposing grayish and very un-American teeth. “Ukrainian.”

“I thought they spoke Russian in the Ukraine.”

“Well, yes. Depends what part of Ukraine. They’re not so different languages, the two. Well—” click of the tongue, eye roll—“not so very much. Numbers are different, days of the week, some vocabulary. My name is spelled different in Ukrainian but in North America it’s easier to use Russian spelling and be Boris, not B-o-r-y-s. In the West everybody knows Boris Yeltsin…” he ticked his head to one side—“Boris Becker—”

“Boris Badenov—”

“Eh?” he said sharply, turning as if I’d insulted him.

“Bullwinkle? Boris and Natasha?”

“Oh, yes. Prince Boris! War and Peace. I’m named like him. Although the surname of Prince Boris is Drubetskóy, not what you said.”

“So what’s your first language? Ukrainian?”

He shrugged. “Polish maybe,” he said, falling back in his seat, slinging his dark hair to one side with a flip of his head. His eyes were hard and humorous, very black. “My mother was Polish, from Rzeszów near the Ukrainian border. Russian, Ukrainian—Ukraine as you know was satellite of USSR, so I speak both. Maybe not Russian quite so much—it’s best for swearing and cursing. With Slavic languages—Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, even Czech—if you know one, you sort of get drift in all. But for me, English is easiest now. Used to be the other way around.”

“What do you think about America?”

“Everyone always smiles so big! Well—most people. Maybe not so much you. I think it looks stupid.”

He was, like me, an only child. His father (born in Siberia, a Ukrainian national from Novoagansk) was in mining and exploration. “Big important job—he travels the world.” Boris’s mother—his father’s second wife—was dead.

“Mine too,” I said.

He shrugged. “She’s been dead for donkey’s years,” he said. “She was an alkie. She was drunk one night and she fell out a window and died.”

“Wow,” I said, a bit stunned by how lightly he’d tossed this off.

“Yah, it sucks,” he said carelessly, looking out the window.

“So what nationality are you?” I said, after a brief silence.

“Eh—?”

“Well, if your mother’s Polish, and your dad’s Ukrainian, and you were born in Australia, that would make you—”

“Indonesian,” he said, with a sinister smile. He had dark, devilish, very expressive eyebrows that moved around a lot when he spoke.

“How’s that?”

“Well, my passport says Ukraine. And I have part citizenship in Poland too. But Indonesia is the place I want to get back to,” said Boris, tossing the hair out of his eyes. “Well—PNG.”

“What?”

“Papua, New Guinea. It’s my favorite place I’ve lived.”

“New Guinea? I thought they had headhunters.”

“Not any more. Or not so many. This bracelet is from there,” he said, pointing to one of the many black leather strands on his wrist. “My friend Bami made it for me. He was our cook.”

“What’s it like?”

“Not so bad,” he said, glancing at me sideways in his brooding, self-amused way. “I had a parrot. And a pet goose. And, was learning to surf. But then, six months ago, my dad hauled me with him to this shaddy town in Alaska. Seward Peninsula, just below Arctic Circle? And then, middle of May—we flew to Fairbanks on a prop plane, and then we came here.”

“Wow,” I said.

“Dead boring up there,” said Boris. “Heaps of dead fish, and bad Internet connection. I should have run away—I wish I had,” he said bitterly.

“And done what?”

“Stayed in New Guinea. Lived on the beach. Thank God anyway we weren’t there all winter. Few years ago, we were up north in Canada, in Alberta, this one-street town off the Pouce Coupe River? Dark the whole time, October to March, and fuck-all to do except read and listen to CBC radio. Had to drive fifty klicks to do our washing. Still—” he laughed—“loads better than Ukraine. Miami Beach, compared.”

“What does your dad do again?”

“Drink, mainly,” said Boris sourly.

“He should meet my dad, then.”

Again the sudden, explosive laugh—almost like he was spitting over you. “Yes. Brilliant. And whores?”

“Wouldn’t be surprised,” I said, after a small, startled pause. Though not too much my dad did shocked me, I had never quite envisioned him hanging out in the Live Girls and Gentlemen’s Club joints we sometimes passed on the highway.

The bus was emptying out; we were only a few streets from my house. “Hey, this is my stop up here,” I said.

“Want to come home with me and watch television?” said Boris.

“Well—”

“Oh, come on. No one’s there. And I’ve got S.O.S. Iceberg on DVD.”

xi.

THE SCHOOL BUS DIDN’T actually go all the way out to the edge of Canyon Shadows, where Boris lived. It was a twenty minute walk to his house from the last stop, in blazing heat, through streets awash with sand. Though there were plenty of Foreclosure and “For Sale” signs on my street (at night, the sound of a car radio travelled for miles)—still, I was not aware quite how eerie Canyon Shadows got at its farthest reaches: a toy town, dwindling out at desert’s edge, under menacing skies. Most of the houses looked as if they had never been lived in. Others—unfinished—had raw-edged windows without glass in them; they were covered with scaffolding and grayed with blown sand, with piles of concrete and yellowing construction material out front. The boarded-up windows gave them a blind, battered, uneven look, as of faces beaten and bandaged. As we walked, the air of abandonment grew more and more disturbing, as if we were roaming some planet depopulated by radiation or disease.

“They built this shit way too far out,” said Boris. “Now the desert is taking it back. And the banks.” He laughed. “Fuck Thoreau, eh?”

“This whole town is like a big Fuck You to Thoreau.”

“I’ll tell you who’s fucked. People who own these houses. Can’t even get water out to a lot of them. They all get taken back because people can’t pay—that’s why my dad rents our place so bloody cheap.”

“Huh,” I said, after a slight, startled pause. It had not occurred to me to wonder how my father had been able to afford quite such a big house as ours.

“My dad digs mines,” said Boris unexpectedly.

“Sorry?”

He raked the sweaty dark hair out of his face. “People hate us, everywhere we go. Because they promise the mine won’t harm the environment, and then the mine harms the environment. But here—” he shrugged in a fatalistic, Russianate way—“my God, this fucking sand pit, who cares?”

“Huh,” I said, struck by the way our voices carried down the deserted street, “it’s really empty down here, isn’t it?”

“Yes. A graveyard. Only one other family living here—those people, down there. Big truck out front, see? Illegal immigrants, I think.”

“You and your dad are legal, right?” It was a problem at school: some of the kids weren’t; there were posters about it in the hallways.

He made a pfft, ridiculous sound. “Of course. The mine takes care of it. Or somebody. But those people down there? Maybe twenty, thirty of them, all men, all living in one house. Drug dealers maybe.”

“You think?”

“Something very funny going on,” said Boris darkly. “That’s all I know.”

Boris’s house—flanked by two vacant lots overflowing with garbage—was much like Dad and Xandra’s: wall-to-wall carpet, spanking-new appliances, same floor plan, not much furniture. But indoors, it was much too warm for comfort; the pool was dry, with a few inches of sand at the bottom, and there was no pretense of a yard, not even cactuses. All the surfaces—the appliances, the counters, the kitchen floor—were lightly filmed with grit.

“Something to drink?” said Boris, opening the refrigerator to a gleaming rank of German beer bottles.

“Oh, wow, thanks.”

“In New Guinea,” said Boris, wiping his forehead with the back of his hand, “when I lived there, yah? We had a bad flood. Snakes… very dangerous and scary… unexploded mine shells from Second World War floating up in the yard… many geese died. Anyway—” he said, cracking open a beer—“all our water went bad. Typhus. All we had was beer—Pepsi was all gone, Lucozade was all gone, iodine tablets gone, three whole weeks, my dad and me, even the Muslims, nothing to drink but beer! Lunch, breakfast, everything.”

“That doesn’t sound so bad.”

He made a face. “Had a headache the whole time. Local beer, in New Guinea—very bad tasting. This is the good stuff! There’s vodka in the freezer too.”

I started to say yes, to impress him, but then I thought of the heat and the walk home and said, “No thanks.”

He clinked his bottle against mine. “I agree. Much too hot to drink it in the day. My dad drinks it so much the nerves are gone dead in his feet.”

“Seriously?”

“It’s called—” he screwed up his face, in an effort to get the words out—“peripheral neuropathy” (pronounced, by him, as “peripheral neuropathy”). “In Canada, in hospital, they had to teach him to walk again. He stood up—he fell on the floor—his nose is bleeding—hilarious.”

“Sounds entertaining,” I said, thinking of the time I’d seen my own dad crawling on his hands and knees to get ice from the fridge.

“Very. What does yours drink? Your dad?”

“Scotch. When he drinks. Supposedly he’s quit now.”

“Hah,” said Boris, as if he’d heard this one before. “My dad should switch—good Scotch is very cheap here. Say, want to see my room?”

I was expecting something on the order of my own room, and I was surprised when he opened the door into a sort of ragtag tented space, reeking of stale Marlboros, books piled everywhere, old beer bottles and ashtrays and heaps of old towels and unwashed clothes spilling over on the carpet. The walls billowed with printed fabric—yellow, green, indigo, purple—and a red hammer-and-sickle flag hung over the batik-draped mattress. It was as if a Russian cosmonaut had crashed in the jungle and fashioned himself a shelter of his nation’s flag and whatever native sarongs and textiles he could find.

“You did this?” I said.

“I fold it up and put it in a suitcase,” said Boris, throwing himself down on the wildly-colored mattress. “Takes only ten minutes to put it up again. Do you want to watch S.O.S. Iceberg?”

“Sure.”

“Awesome movie. I’ve seen it six times. Like when she gets in her plane to rescue them on the ice?”

But somehow we never got around to watching S.O.S. Iceberg that afternoon, maybe because we couldn’t stop talking long enough to go downstairs and turn on the television. Boris had had a more interesting life than any person of my own age I had ever met. It seemed that he had only infrequently attended school, and those of the very poorest sort; out in the desolate places where his dad worked, often there were no schools for him to go to. “There are tapes?” he said, swigging his beer with one eye on me. “And tests to take. Except you have to be in a place with Internet and sometimes like far up in Canada or Ukraine we don’t have that.”

“So what do you do?”

He shrugged. “Read a lot, I guess.” A teacher in Texas, he said, had pulled a syllabus off the Internet for him.

“They must have had a school in Alice Springs.”

Boris laughed. “Sure they did,” he said, blowing a sweaty strand of hair out of his face. “But after my mum died, we lived in Northern Territory for a while—Arnhem Land—town called Karmeywallag? Town, so called. Miles in the middle of nowhere—trailers for the miners to live in and a petrol station with a bar in back, beer and whiskey and sandwiches. Anyway, wife of Mick that ran the bar, Judy her name was? All I did—” he took a messy slug of his beer—“all I did, every day, was watch soaps with Judy and stay behind the bar with her at night while my dad and his crew from the mine got thrashed. Couldn’t even get television during monsoon. Judy kept her tapes in the fridge so they wouldn’t get ruined.”

“Ruined how?”

“Mold growing in the wet. Mold on your shoes, on your books.” He shrugged. “Back then I didn’t talk so much as I do now, because I didn’t speak English so well. Very shy, sat alone, stayed always to myself. But Judy? She talked to me anyway, and was kind, even though I didn’t understand a lick of what she said. Every morning I would go to her, she would cook me my same nice fry. Rain rain rain. Sweeping, washing dishes, helping to clean the bar. Everywhere I followed like a baby goose. This is cup, this is broom, this is bar stool, this pencil. That was my school. Television—Duran Duran tapes and Boy George—everything in English. McLeod’s Daughters was her favorite programme. Always we watched together, and when I didn’t know something? She explained to me. And we talked about the sisters, and we cried when Claire died in the car wreck, and she said if she had a place like Drover’s? she would take me to live there and be happy together and we would have all women to work for us like the McLeods. She was very young and pretty. Curly blonde hair and blue stuff on her eyes. Her husband called her slut and horse’s arse but I thought she looked like Jodi on the show. All day long she talked to me and sang—taught me the words of all the jukebox songs. ‘Dark in the city, the night is alive…’ Soon I had developed quite proficiency. Speak English, Boris! I had a little English from school in Poland, hello excuse me thank you very much, but two months with her I was chatter chatter chatter! Never stopped talking since! She was very nice and kind to me always. Even though she went in the kitchen and cried every day because she hated Karmeywallag so much.”

It was getting late, but still hot and bright out. “Say, I’m starving,” said Boris, standing up and stretching so that a band of stomach showed between his fatigues and ragged shirt: concave, dead white, like a starved saint’s.

“What’s to eat?”

“Bread and sugar.”

“You’re kidding.”

Boris yawned, wiped red eyes. “You never ate bread with sugar poured on it?”

“Nothing else?”

He gave a weary-looking shrug. “I have a coupon for pizza. Fat lot of good. They don’t deliver this far out.”

“I thought you had a cook where you used to live.”

“Yah, we did. In Indonesia. Saudi Arabia too.” He was smoking a cigarette—I’d refused the one he offered me; he seemed a little trashed, drifting and bopping around the room like there was music on, although there wasn’t. “Very cool guy named Abdul Fataah. That means ‘Servant of the Opener of the Gates of Sustenance.’ ”

“Well, look. Let’s go to my house, then.”

He flung himself down on the bed with his hands between his knees. “Don’t tell me the slag cooks.”

“No, but she works in a bar with a buffet. Sometimes she brings home food and stuff.”

“Brilliant,” said Boris, reeling slightly as he stood. He’d had three beers and was working on a fourth. At the door, he took an umbrella and handed me one.

“Um, what’s this for?”

He opened it and stepped outside. “Cooler to walk under,” he said, his face blue in the shade. “And no sunburn.”

xii.

BEFORE BORIS, I HAD borne my solitude stoically enough, without realizing quite how alone I was. And I suppose if either of us had lived in an even halfway normal household, with curfews and chores and adult supervision, we wouldn’t have become quite so inseparable, so fast, but almost from that day we were together all the time, scrounging our meals and sharing what money we had.

In New York, I had grown up around a lot of worldly kids—kids who’d lived abroad and spoke three or four languages, who did summer programs at Heidelberg and spent their holidays in places like Rio or Innsbruck or Cap d’Antibes. But Boris—like an old sea captain—put them all to shame. He had ridden a camel; he had eaten witchetty grubs, played cricket, caught malaria, lived on the street in Ukraine (“but for two weeks only”), set off a stick of dynamite by himself, swum in Australian rivers infested with crocodiles. He had read Chekhov in Russian, and authors I’d never heard of in Ukrainian and Polish. He had endured midwinter darkness in Russia where the temperature dropped to forty below: endless blizzards, snow and black ice, the only cheer the green neon palm tree that burned twenty-four hours a day outside the provincial bar where his father liked to drink. Though he was only a year older than me—fifteen—he’d had actual sex with a girl, in Alaska, someone he’d bummed a cigarette off in the parking lot of a convenience store. She’d asked him if he wanted to sit in her car with her, and that was that. (“But you know what?” he said, blowing smoke out of the corner of his mouth. “I don’t think she liked it very much.”

“Did you?”

“God, yes. Although, I’m telling you, I know I wasn’t doing it right. I think was too cramped in the car.”)

Every day, we rode home on the bus together. At the half-finished Community Center on the edge of Desatoya Estates, where the doors were padlocked and the palm trees stood dead and brown in the planters, there was an abandoned playground where we bought sodas and melted candy bars from the dwindling stock in the vending machines, sat around outside on the swings, smoking and talking. His bad tempers and black moods, which were frequent, alternated with unsound bursts of hilarity; he was wild and gloomy, he could make me laugh sometimes until my sides ached, and we always had so much to say that we often lost track of time and stayed outside talking until well past dark. In Ukraine, he had seen an elected official shot in the stomach walking to his car—just happened to witness it, not the shooter, just the broad-shouldered man in a too-small overcoat falling to his knees in darkness and snow. He told me about his tiny tin-roof school near the Chippewa reservation in Alberta, sang nursery songs in Polish for me (“For homework, in Poland, we are usually learning a poem or song by heart, a prayer maybe, something like that”) and taught me to swear in Russian (“This is the true mat—from the gulags”). He told me too how, in Indonesia, he had been converted to Islam by his friend Bami the cook: giving up pork, fasting during Ramadan, praying to Mecca five times a day. “But I’m not Muslim any more,” he explained, dragging his toe in the dust. We were lying on our backs on the merry-go-round, dizzy from spinning. “I gave it up a while back.”

“Why?”