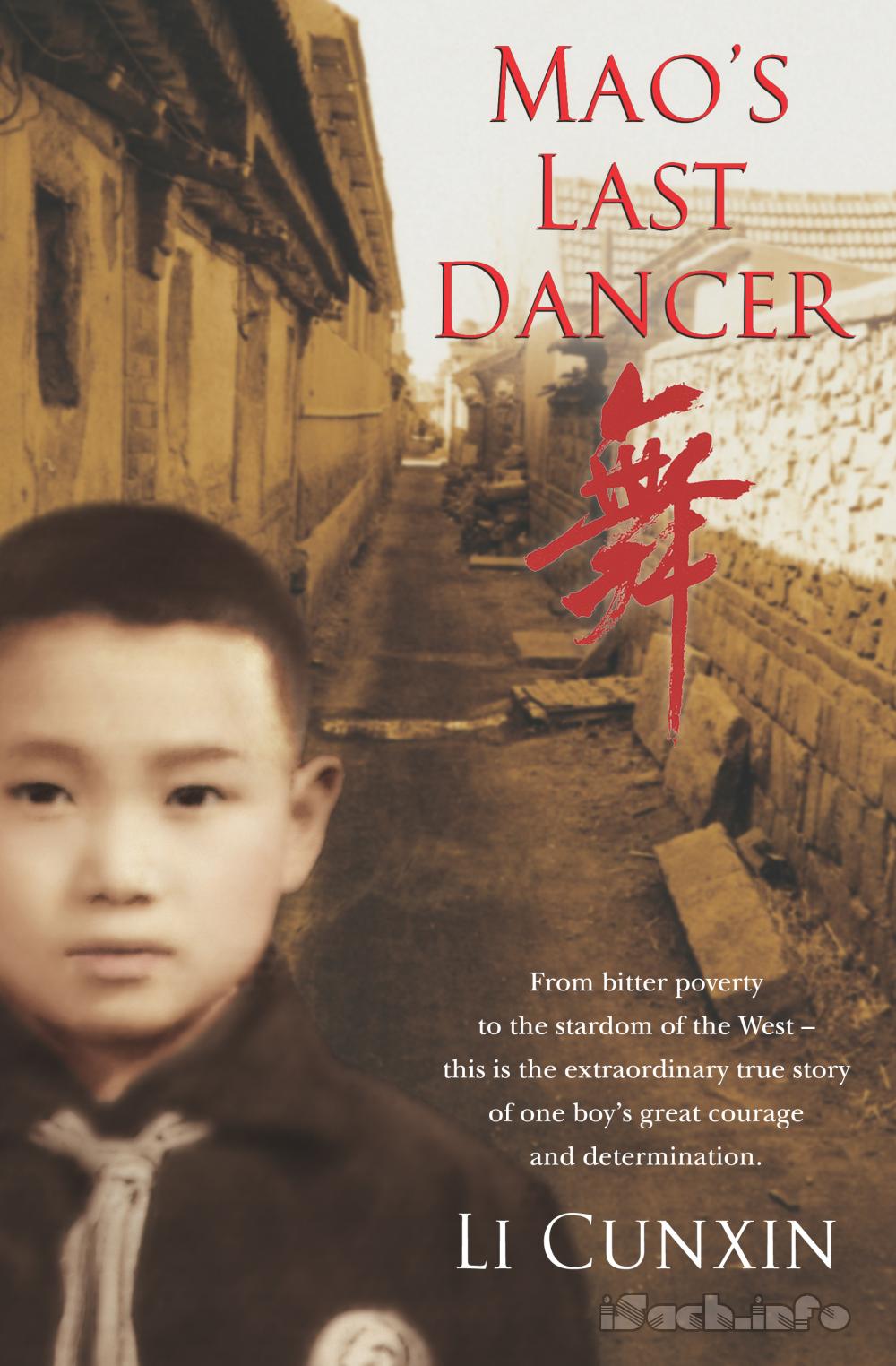

3 A Commune Childhood

B

y 1969, when I was about eight years old, the poverty around Laoshan and our commune had worsened. I remember going with several of my friends to the beach one day, an hour's journey away by foot, to find clams and oysters or, if we were lucky, a dead fish that was washed up on the shore. We each carried our own bamboo basket in our arms and a small spade over our shoulders. My parents always warned us never to go into the water because of the rips.Many people were already there, also searching, by the time we arrived. After about half an hour, we'd found nothing except empty seashells. The beach was so clean and bare it was as if even the sea creatures had abandoned us.

Halfway home I suggested to my friends that we should make a slight detour and sneak into the nearby airport to try and find some half-burnt coal. During the Second World War the Japanese had built this airport as one of their main cargo facilities. Now there were only a few People's Liberation Army guards and some old cargo planes left. The Japanese used coal and half- burnt coal as part of the filler under the runway, and the outer part of the runway had already been dug away by desperate people. Since then the guards had tightened security.

I had only been there once before, with one of my older brothers. There was a line of big trees along the edge of the airport and a small ditch for water drainage. The ditch was dry at that time of the year and we crept along it for about fifteen minutes, bending our bodies down into the ditch so the guards couldn't see us.

There was still evidence of half-burnt coal there, about half a yard below the surface, and very hard to loosen. But digging half-burnt coal was like digging gold for us. We had no sense of time and we eventually had our baskets full. Carrying heavy baskets with a bent body, though, proved too difficult for us eight-year-olds. About halfway out, one of the boys slowly straightened up and was spotted by the military guards. They immediately fired bullets into the air and started to chase us. We were scared witless. We dumped our baskets and spades, and ran for our lives.

I rushed breathlessly home. It was half past one in the afternoon. "There is some food in the wok for you," my fifth brother Cunfar said. Niang had left some dried yams and pickled turnips for me.

"Where is Niang?" I asked him as I ate my lunch.

"She went back to work in the fields," he replied. Cunfar only had morning classes at school that day. There weren't enough classrooms for everyone to go for a full day.

"Where have you been?" he asked me.

I told him what had happened at the airport. He frowned. "You dropped your basket and spade there?"

"Yes, I had no choice! The soldiers would have killed us if they'd caught us!"

"No, they wouldn't," he replied.

"Yes, they would! They even fired bullets at us!"

"You have to go back and get your basket and spade. We cannot buy new ones—our parents have no money," he said.

"I'll never go anywhere near that airport again!" But he did eventually talk me into going back. At the edge of the ditch I refused to go any further and pointed to where we'd dropped our baskets and spades. He went to look, but the guards had confiscated them. Only some half-burnt coals were left scattered around the ditch.

Our winters in those days were bitterly cold in Qingdao, but as well as having to cope with the lack of coal, we also had to deal with lice. They lived with us in our cotton quilts, coats and pants. Unlike our summer clothes, which our niang washed regularly, our quilted winter coats and pants couldn't be washed because they were painstakingly made with loose cottonwool pieces that would have shrivelled into balls in the water. The only proper way to wash our winter clothes was to take them apart and restart the whole messy, tiring, time-consuming process of making them all over again. Our niang would spread the cottonwool on our kang and the fibres would fly everywhere, like white dust. She'd have white fibres all over her black hair and clothes. She'd look like a white cotton ball herself. But once they were made, our winter clothes would last the entire season.

The only real way to combat lice was to keep clean. Every weekend our niang would heat up huge woks of water for us and tip the water into an old wooden washing-basin. Each of us had a piece of thin washing-cloth, and we'd soap our bodies and help to wash each other's backs. If one family member had lice, the rest of the family would too: they bred and multiplied so quickly. It wasn't just our family—lice were everywhere in China. Everyone scratched constantly. In the evenings after we took off our clothes and got under the quilts, our niang always flipped our clothes inside out, trying to kill the lice with her thumbnails. By the end of the evening her thumbnails would be covered in blood. She was such an expert at killing those little bloodsuckers: she had the most incredible eyesight, despite the dim light. We had a single twenty-watt bulb hanging down from the ceiling in each room (electricity had come to our village the year before I was born). Generally, the commune would cut off power at eight every night. Then Niang would light a small kerosene lamp and patiendy continue her work. But she could never get rid of the lice completely because they lived inside the seams of the fabric. They only came out to suck our blood during the day when we wore our clothes.

I have so many vivid childhood memories like these, but I do not ever remember going to a doctor or hospital as a child: not that I didn't get sick, but we could never afford it. The only time I got close to a medical person was waiting in line for a barefoot nurse to give us smallpox shots. We had to wait in long lines in our commune square with our sleeves rolled up. The nurse used the same needle to inject everybody, and small pieces of alcohol- soaked cottonwool to clean the needle heads and skin. Mothers held screaming babies in their arms, but children aged five or over were expected to be brave enough to go up the line by themselves. Crying wasn't an option, no matter how much it scared us or how much it hurt. When I cut myself I was told by my parents to swipe my fingers on the windowsill to gather some dust to put on the cut and stop the bleeding. This was our Band-aid and antiseptic all in one.

Our niang's remedy for severe coughs, however, involved a snakeskin collected in the fields during autumn when snakes shed their skin. She would wrap the snakeskin around a piece of green onion and make me eat it in front of her. All of it. The snakeskin was like tasteless plastic and it looked disgusting. It always made me want to vomit, but it was the most effective treatment for sore throats and coughs we had.

One day my face and neck swelled up for several days because of infected glands. Niang took me to a neighbour and he brought out a calligraphy set. He ground the black ink stick in an ink plate and mixed in some water. He dipped in his paintbrush. I thought he was going to write a secret recipe to cure my infection, but instead he asked me to close my eyes and he started to draw on my face. As he drew, he uttered some strange words to the god of healing. I didn't understand the words, but I enjoyed the cool sensation of the ink on my skin. I felt as though someone other than my niang was pampering me for the first time in my life. Eventually my entire face and neck were black. I looked scary, comical—like an evil Beijing Opera character.

I had to keep the ink on my face and neck for two whole days. I refused to go outside. My brothers just kept laughing at me. Luckily I hadn't started going to school yet, so I didn't have to face teachers and classmates as well. My swelling disappeared within two days, but still I wonder if the swelling would have gone away anyway, without the embarrassing made-up face.

Another childhood ordeal for us was warts, which we called "monkeys". An elderly man in our village, who we called the "Wuho man", told my niang that the best way to eradicate monkeys was to wet them on the grain grinder on the day of rain. The Wuho man was in his late seventies. He was a funny old man with a good sense of humour. He had poor eyesight, rotten teeth and a long silver beard. He always had a palm-leaf fan in his hand and smoked an ancient pipe. His walk was rather stylish, with his hands folded behind his back, and he coughed and spat a lot.

He told our niang that for this treatment to work we had to keep our mouths shut on the way to and from the grinder.

So, just after rain one day, my niang said to me, "Take Jing Tring to the grinder and wet your monkeys with the water from it."

"But you promised me that I could play with Sien Yu after the rain stopped!" I replied. I didn't want to go. I thought it would be a waste of time. And I hated always having to look after Jing Tring.

"You can't go and play with Sien Yu unless you take Jing Tring to the grinder first," she threatened.

I so eagerly wanted to play with my friend that reluctantly I agreed.

Before we left for our five-minute walk to the grain grinder, our niang reminded us, "Remember, don't talk to anyone! This treatment won't work if you utter a single word on the way there and back."

I was very annoyed. I felt it would be an easy task for me not to speak but it would be hard for Jing Tring. He was still so little. "I'll kill you if you open your mouth, do you understand?" I said to him just before we stepped out our gate. He just nodded. I took his hand and embarked on this special mission.

The first couple of minutes we managed to keep our mouths shut because we didn't meet anyone. But once we'd gone about halfway, we saw Sien Yu's mother coming towards us. "Ni hao, liu su. Ni hao, qi su," she said politely, acknowledging us as sixth and seventh uncles. "Sien Yu is waiting for you at home. Are you on your way there?" she asked.

"Ni hao, zhi xi fu." I returned her acknowledgement, greeting her as my nephew's wife. "I'll be coming soon!"

I couldn't believe it. I couldn't believe I was the stupid one, not Jing Tring. We had to go back and start our journey all over again.

Jing Tring was very unhappy and didn't want to cooperate. He kept saying, "I'm tired! I'm tired! I'm too tired to walk!"

"If you don't go," I threatened him, "your monkeys will spread all over your arms, your body, your face and maybe even in your eyes!"

"I don't want to go again! I can't!" he said.

I was desperate by this time. I didn't want to miss out on playing with Sien Yu. "Tell you what, I'll take you with me to Sien Yu's house if you finish this task with me." Jing Tring always wanted to do exactly what I did.

"You promise?" he asked excitedly.

"Yes, I promise," I replied.

"You dare to spit on it?" he asked again.

Annoyed, I spat on the ground and stamped my foot on it so that if the promise wasn't kept it would bring me unthinkable bad luck.

We went back home and started our journey again. Just as I thought things were going smoothly, we saw Sien Yu coming towards us, excitedly shouting, "What's taken you so long? I was on my way to your house to get you."

Just as I put my finger to my mouth to tell him to keep quiet, Jing Tring shouted happily, "My sixth brother promised me that I can play with you after our secret mission!" We had failed on our second try, and the old Wuho man had said that we were only allowed to try this journey three times in a single day. It was just like Jing Tring to ruin everything, I thought.

This time my little brother adamantly refused to walk. Even my promise of taking him to Sien Yu's house didn't work. "I want to stay home, I want to stay home!" he screamed.

"You children, the only thing you know how to do well is eat!" our niang said to us when we arrived back home for the second time. "Don't tell me you can't even keep your mouths shut for a few minutes."

This time, out of desperation, I carried my little brother on my back. "Shut your eyes. Close your mouth. If I hear a single sound from you, I will throw you into the well and you can spend the rest of your life with the frogs!" That scared him so much that he did as he was told. This time we completed our task, and a month later our warts had completely disappeared.

• • •

Despite our hardships, however, there were occasional joys too in our childhood. The one time of the year that we all looked forward to, the one time when we would be guaranteed wonderful food, was the Chinese New Year.

Our niang had to make and steam many bread rolls for the Chinese New Year, as gifts for our relatives. She made them in the shape offish and peaches, representing peace and prosperity, and gold bars representing wealth. Making the bread was time-consuming. The bread rolls would split if the dough had not been kneaded perfectly. She would be too embarrassed to take the split ones to our relatives, so we would keep those for ourselves. I always wished for more split ones, but she was such a perfectionist there would be very few of those and she rarely had sufficient flour to make enough bread for the gifts, let alone for us. During the holiday season we often had corn bread, second best to wheat bread, and it was such a treat.

Before dark on New Year's Eve, my dia and my fourth uncle would take me and my brothers to my ancestors' graveyard. We took bottles of water, representing food and wine, and stacks of yellowish rice paper stamped with the shape of old gold coins, which symbolised spending money. We took many bunches of incense, representing gold bars, and carried paper lanterns. All the children had pockets full of firecrackers. We spread the rice papers and stuck the incense on top of each grave. After we lit the paper money and the incense, we would kneel in front of each tomb and kowtow three times, calling out each ancestors' name, following a strict order, starting with the eldest of us and ending with the youngest.

"Dia, how can the dead people hear us if they are dead?" I asked.

"They know," he replied with his usual brevity.

Just before we left the graveyard to go home for our special dinner, we asked each of our ancestors to follow us home for the New Year's holiday. Our dia and our fourth uncle poured the bottles of water in front of each grave. On the way home we made sure our lanterns were brightly lit, so our ancestors' spirits could see clearly the road ahead. The children lit the firecrackers to wake the ancestors up. "Xing gan wo men hui jia. Lu bu ping. Man man zou." Our dia and our uncle would ask our ancestors to walk slowly and not trip on the uneven road. They talked to our ancestors as though they were still alive. My brothers and I thought this was funny but we had to take this occasion very seriously. Our ancestors' spirits lived on, like gods in a better world, because they had been kind people before they died. They had the power to help us, influence our well-being and our fate.

The meal that night was Niang's favourite to cook, because this was the only time she had enough good ingredients. She had saved all year long for this. Cold dishes came first: marinated jellyfish with soy sauce and a touch of sesame oil; seaweed jelly with smashed up garlic and soy sauce; marinated salty peanuts and pig-trotter jelly. Then hot dishes: fried whole flounder, and we always pushed the head to our dia's side of the plate. It was the most precious part of the fish to have. But our dia didn't touch it until our niang came to sit down, and then he would push it to her side of the plate. Then there was a steaming egg dish with green chives and rice noodles. There would have been at least ten eggs in it! It was so delicious that it just melted in my mouth. There were several vegetable dishes too and they all had small pieces of meat in them. The aroma of all this delicious food, mixed with the Chinese rice & wine, the incense and the pipe smoke, was unforgettable. It was so distinctively the Li family smell. And it only occurred once a year, on that special Chinese New Year's Eve.

I always volunteered to help Niang push the windbox on those nights. I dearly wanted to stay on the kang to feast on her delicious food with the rest of the family, but even more I wanted to be with my niang on this special night. I didn't want her to be cooking alone. She would bubble with happiness while she cooked. "Da kai huo tao. Rang ta tiao wu." Let the flame dance now, she would say. Or, "Rang huo tao man xia lai." Slow down the fire, let it simmer. Even pushing the windbox was fun.

That night we would use black coal, not half-burnt coal, and the flame would flare immediately with each push and pull of the windbox. I often wondered if the god of fire, if there was one, was happy that particular night. I wished he would be happy all the time.

Everything was special and magical that night. Each dish tasted better than the previous one served. Everyone chatted enthusiastically, but the one who talked the most that night was our dia. Happiness filled up everyone's hearts. We would forget hardship. We felt privileged. There were always too many dishes to fit on the wooden tray and many would end up on the kang. I wondered why we didn't spread these delicious dishes throughout the year. How much could we eat in one night?

The meal always ended with steaming pork-and-cabbage dumplings, all handmade by our niang. They looked precious and smelt exquisite! I always saved plenty of room for them. They truly were a labour of love. Our niang would put a one-fen coin into a dumpling and whoever found it was destined to have luck throughout the year. One year nobody found that fen, even though our niang swore she'd put it in. Did someone eat it without even noticing? we asked. Nobody was surprised. We swallowed those dumplings as if we were wolves.

The very first bowl of dumplings to be served was lucky food, for the gods of the kitchen, of harvest, prosperity, long life and happiness. The second bowl of dumplings was for our ancestors. Before our niang placed each bowl of dumplings at the centre of the table, with incense on either side, she would pour some broth onto the ground in four directions. "Gods, my kind gods," she would murmur, "please eat our humble food. We are blessed by your generosity." The square table was always placed in the middle of the room, against the northern wall. Before Chairman Mao and the Cultural Revolution we would have displayed a family tree and a picture of the god of fortune too, on the wall just above the table. But this was an old tradition now, a threat to communist beliefs. Any family doing this would be regarded as counter-revolutionary and there were heavy penalties, including jail.

Nobody was to touch those dumplings my niang left at the centre of the table, but they always mysteriously disappeared overnight. "The gods and our ancestors have eaten them," our niang would say. I thought this was incredible, and believed her wholeheartedly.

After the meal we would go from house to house to pay our respects and wish everyone a happy and prosperous New Year. Every gate in the village was wide open. Nobody was supposed to sleep. We would play tricks on our friends if we caught any of them sleeping. Once we tied a firecracker to a friend's ankles and when he moved his legs in his sleep the firecracker went off and gave him a dreadful fright.

After midnight, firecrackers could be heard everywhere and would last throughout the night. Thousands of small red-and-white pieces of firecracker paper splattered around the streets. Many of the firecrackers we made ourselves. My favourite was the "double kicker". It was as long as an adult's finger, and once we lit it the first explosion happened in our hand and it would shoot off for about ten or fifteen yards, when the second explosion would go off.

On New Year's Day we would sleep until midmorning. Everyone was exhausted, but nobody cared. The holiday spirit lived on.

On alternate years, we went to one of our aunties' houses on New Year's Day. I loved my aunts, but my youngest auntie's house had more action, and the meals in her house would sometimes last for three or four hours. She was a beautiful lady and a good cook, with three girls and a boy, and a husband who would sing and tell us stories. He was one of the best furniture painters in Qingdao. Often he would tell us about the knowledge and tradition behind painting a piece of wood. He was very funny. He loved drinking rice wine and once he'd had one small glass his voice would rise an octave and he would begin to sing tunes from some of the old Beijing Operas. He also had many photos of himself taken in different cities around China. I loved looking at them. It was unusual for a person to travel so much in China then. Most people never left the city they were born in, but because of my uncle's painting skills he was invited to attend painting seminars throughout China. I was fascinated by these beautiful photos, by the places he'd been to. We only had a few photos in our house, and I asked my parents why. "You will lose a layer of skin with each photo taken," our dia replied, "and you only have so many layers of skin to lose before you die."

"Then why did my uncle have so many pictures taken? He is still alive and well," I asked.

"Just wait," our dia would say ominously.

Our niang always sighed upon hearing our dia's explanation. She knew we were simply too poor to afford them.

The second day of the New Year was the day we farewelled our ancestors. We would light lanterns and incense and show our ancestors the way back to their graves. We would shower them with more symbolic food, drink and money, and wish them a year of good fortune and peace.

On the third day of the New Year, married daughters would visit their families. Our niang would take two or three sons with her, dressed up in our best clothes, and she would make a huge fuss about how we should behave. She took two basketfuls of bread rolls for her father and eldest brother. This was an important day for her. It was as though she had to show her family how well she'd done being married to the Li family.

We left our house before half past seven in the morning to catch the eight o'clock bus to the city. The rickety old bus was always crowded with people squeezed tightly in. We often sat on each other's laps for the one-hour trip because the elderly always had first preference for seats, and the old bus clucked and chuckled along so slowly that it seemed as if the wheels would fall off or the engine would stop any minute. The bus door had to be pulled hard to open and shut it. At each stop, people pushed their way on or off, but many people couldn't get on at all because there was no room and many missed their stops altogether. One time we all had to walk because the bus really did break down halfway there. When the next bus arrived an hour later, it was as full as the bus we'd just been on.

After our niang's mother passed away, her father married a country girl the same age as our niang and moved his family to Qingdao City. Better times had come for him. He was a carpenter. The city people could afford to pay more than the country peasants for his carpentry work.

My grandfather's place was on the top floor of a very old three- storey concrete building that looked as though it would crumble any time. The stairs were badly chipped, and it probably hadn't been painted since the day it was built. His apartment had two small rooms. My grandparents' room was the slightly larger room, and our niang's stepbrother and stepsister slept in another room on a tiny double bed made by my grandfather. There was no storage space. Clothes and other things had to go under their beds or hang from the ceiling or be kept under a piece of plastic outside.

About twenty families on their floor shared one bathroom for men and one for women. Both bathrooms had two toilets—concrete holes in the ground—and they always smelt dreadfully, even from my grandparents' apartment and theirs was the furthest away! I couldn't imagine how much worse the smell would be in summer. We only visited during the Chinese New Year when the weather was cold. One of the toilet holes at least, sometimes both, was blocked and occasionally all the overflowing shitty stuff even froze to the steps. I would always find an excuse to disappear onto the streets when I was desperate for a wee.

But the toilet smell wasn't the only smell we had to contend with at their place. My grandparents both chain-smoked pipes and their two tiny rooms were constandy filled with smoke. Luckily we never stayed inside long. In fact we always made sure we didn't by making lots of noise while the adults were talking. Sometimes our grandfather would tell our niang to control her "undisciplined brats". But we never really got into trouble. Niang was just as relieved as we were to leave that stinking, miserable place.

Our second stop on that trip was at our niang's eldest brother's house, Big Uncle's. He was three years younger than her and they were very close. Big Uncle was the most educated man in our niang's family. He was politically astute, and the head of the propaganda department for the Building Materials Bureau in Qingdao. He had a son and two daughters. Their living standard was much higher than ours: we considered their three-room apartment very luxurious.

Big Uncle loved card games and also enjoyed playing a word guessing game between the adults. The loser had to keep drinking rice wine, and the more they drank the more likely they were to lose. All the children would form a circle, cheering the adult they wanted to succeed.

"I won! Drink! Drink!" Big Uncle would declare.

"Shui shuo ni ying le? Zailai, zailai!" The opponent wouldn't agree with Big Uncle's declaration, and they would get into heated arguments. Often they were shouting so loud the women had to ask them to quieten down. Afterwards I would ask Big Uncle what story each word represented, and sometimes he would tell me a famous fable. He was an animated storyteller, humorous and witty. I thought maybe that was why he was head of the propaganda department.

The fifteenth day of the New Year was always dreaded. It marked the end of the Chinese New Year and the beginning of our harsh life once again. We were told this night was traditionally enjoyed by the emperor's family as the "Night of Lights". Beijing and other big cities would display magical lights and set off many fireworks. But the best we could do was to make torches from can-dlewax. We would walk around the house and shine the torches into every corner to keep the evil spirits away. Our fourth uncle always took huge pleasure in making the torches for us. We gathered wooden sticks and he would wrap pieces of white cotton tightly around the tip and dip them into a big pot of melted candlewax. Sometimes he even let us do some dipping if we behaved ourselves. I loved watching the wax harden on the tip of the sticks, and even more I enjoyed running and twisting the torch around, making different shapes in the dark. My favourite shape to make was a dragon, and I pretended my torch was a magical Kung Fu weapon as I twirled it around.

Our parents always warned us to keep the torches away from the piles of dried grass or hay which were used to ignite the coal and which every family stored in their front yard. Once I remember a neighbour's house nearly caught fire because a five- year-old boy hid in their haystack with a lit incense in his hand. The boy barely escaped from the burning haystack alive.

Chinese New Year was our dia's only holiday. Since the weather was normally very cold and the fields frozen at that time of the year, there was not much work to do on our little piece of land. Our main outdoor activity during these days was kite flying. I often sat myself apart from the other kite-flying boys. For them this was just another game, but for me this time was special. My kite wasn't ordinary. It was my messenger to the gods, my secret communication channel.

Our dia was an expert kite-maker. He made very simply shaped kites: a square, a six-pointed star and a butterfly. He used an ancient Chinese cutting knife, the size of a Swiss army knife, to thinly slice the bamboo sticks. Then he'd tie the corners with thread and glue rice paper over the frame. To counter the weight we would hang long strips of cloth on the tail. The kite string was pieced together from anything we could find.

I adored making kites with our dia. This was one of the few playful times I could have with him. He would take us up to the fields on the Northern Hill and he'd sit next to me and tell me stories from his childhood. I never wanted these special moments to end.

At this time of the year there was always thick snow in the fields. The freezing, howling wind felt like small sharp knives cutting into my skin. The fields smelt, as always, of human manure. My dia would help my kite into the sky, then stand up, ready to leave. "Are you all right now? I'm going home. I've got work to do."

"Dia, can you tell me a story before you go?"

"I've told you all the stories I have."

"Please tell me `The Frog in the Well` story again," I begged. He sat next to me, put his arm around my shoulder, and began:

There was a frog that lived in a small, deep well. He knew nothing but the world he lived in. His well and the sky he could see above it were his entire universe.

One day he met a frog who lived in the world above. "Why don't you come down and play with me? It's fun down here," the frog in the deep well asked.

"What's down there?" the frog above asked.

"We have everything down here. You name it. The streams, the undercurrent, the stars, the occasional moon, and we even get flying objects coming down from the sky sometimes," the frog in the well answered.

The frog on the land sighed. "My friend, you live in a confined world. You haven't seen what's out here in the bigger world." The frog below was very annoyed. "Don't you tell me that you have a bigger world than ours! My world is big. We see and experience everything the world has to offer," the well frog said.

"No, my friend. You can only see the world above you through the size of the well. The world up here is enormous. I wish I could show you how big it is," the frog above replied.

The frog in the well was angry now. "I don't believe you! You are telling me lies! I'm going to ask my dia." He told his dia about his conversation with the frog on the land. "My son," he said with a saddened heart, "your friend is right. I heard there is a much bigger world up there, with many more stars than we can see from here."

"Why didn't you tell me about it earlier?" the little frog asked.

"What's the use? Your destiny is down here in the well. There is no way you can get out of here," the father frog replied.

The little frog said, "I can, I can get out of here. Let me show you!" He jumped and hopped, but the well was too deep and the land was too far above.

"No use, my son. I've tried all my life and so did your forefathers. Forget the world above. Be satisfied with what you have, or it will cause you such misery in life."

"I want to get out, I want to see the big world above!" the little frog cried determinedly.

"No, my son. Accept fate. Learn to live with what is given," his dia replied.

So the poor little frog spent his life trying to escape the dark, cold well. But he couldn't. The big world above remained only a dream.

"Dia, are we in a well?" I asked.

He thought for a while. "Depends on how you look at it. If you look at where we are from heaven above, yes, we're in a well. If you look at us from below, we're not in a well. Will you call where we are heaven? No, definitely not," he replied.

I thought about that poor frog in the well many times. I felt sad and frustrated. We were all trapped in a well too, and there was no way out.

So I would use my kite to send messages to the gods. I found refuge from the freezing wind in a ditch and I carried a pocketful of small paper strips. I wet both ends of the paper with my tongue and looped it around the string of the kite. The strong wind pushed my paper loop up towards the kite.

The wish I sent up with my first paper loop was for my niang's happiness and long life. I told the gods that she was the kindest, most hardworking niang, but she was so poor and deserved better. I challenged the gods and said that if they really existed and were as powerful as people were telling me they were, then they should change my niang's situation and grant her a happy life. Suddenly I would get angry with the gods for not being fair to my niang. Then I would become frightened, and beg them for forgiveness. After that, I would send a second wish, for my dia's good health.

But my last wish was my most important of all. I looped a third piece of paper around the kite string, and wished to get out of the deep, dark well. I confessed to the gods all my inner feelings. I made my secret wish. I daydreamed about all the beautiful things in life that were not mine. I begged them for more food for my family. I begged the gods to get me out of the well so I could help my family. My imagination travelled far beyond the far-away kite into my own special land.

My messages to the gods often got stuck at the knots in the string along the way. I had to shake and jerk the string to get my messages past the knots. Sometimes I would have many messages stuck at different knots on the kite string, and often I was the last one to leave the freezing-cold fields on the Northern Hill. But the cold always gave in to my imagination. It was my imagination that kept my heart warm and my hopes alive.

ePub

ePub A4

A4