Part 4

W

ere you very hurt by women?' she asked, realising at once what an idiotic question it was, straight out of some manual entitled Everything Women Should Know If They Want to Get Their Man.'No, they never hurt me. I was very happy in both my marriages. I was unfaithful and so were they, just like any other normal couple. Then, after a while, I simply lost interest in sex. I still felt love, still needed company, but sex • •• but, why are we talking about sex?'

'Because, as you yourself said, I'm a prostitute.'

'My life isn't very interesting really. I'm an artist who found success very young, which is rare, and even rarer in the world of painting. I could paint anything now and it would be worth a fortune, which, of course, infuriates the critics because they think they are the only ones who know about “art”. Other people think I've got all the answers, and the less I say, the more intelligent they think I am.'

He went on talking about his life, how every week he was invited to something somewhere in the world. He had an agent who lived in Barcelona - did she know where that was? Yes, Maria knew, it was in Spain. This agent dealt with everything to do with money, invitations, exhibitions, but never pressured him to do anything he didn't want to do, now that, after years of work, there was a steady demand for his paintings.

'Do you find my story interesting?' he asked, and his voice betrayed a touch of insecurity.

'It's certainly an unusual one. Lots of people would like to be in your shoes.'

Ralf wanted to know about Maria.

'Well, there are three of me, really, depending on who I'm with. There's the Innocent Girl, who gazes admiringly at the man, pretending to be impressed by his tales of power and glory. Then there's the Femme Fatale, who pounces on the most insecure and, by doing so, takes control of the situation and relieves them of responsibility, because then they don't have to worry about anything.

And, finally, there's the Understanding Mother, who looks after those in need of advice and who listens with an allcomprehending air to stories that go in one ear and out the other. Which of the three would you like to meet?'

'You.'

Maria told him everything, because she needed to - it was the first time she had done so since she left Brazil. She realised that, despite her somewhat unconventional job, nothing very exciting had happened apart from that week in Rio and her first month in Switzerland. Otherwise, it had been home, work, home, work - and nothing else.

When she finished speaking, they were sitting in another bar, this time on the other side of the city, far from the road to Santiago, each of them thinking about what fate had reserved for the other.

'Did I leave anything out?' she asked.

'How to say “goodbye”.'

Yes, it had not been an afternoon like any other. She felt tense and anxious, for she had opened a door which she didn't know how to close.

'When can I see the whole painting?'

Ralf gave her the card of his agent in Barcelona.

'Phone her in about six months' time, if you're still in Europe. The Faces of Geneva, famous people and anonymous people. It will be exhibited for the first time in a gallery in Berlin. Then it will tour Europe.'

Maria remembered her calendar, the ninety days that remained, and the dangers posed by any relationship, any bond. She thought:

'What is more important in life? Living or pretending to live? Should I take a risk and say that this has been the loveliest afternoon I've spent in all the time I've been here? Should I thank him for listening to me without criticism and without comment? Or should I simply don the armour of the woman with willpower, with the “special light”, and leave without saying anything?'

While they were walking along the road to Santiago and while she was listening to herself telling him about her life, she had been a happy woman. She could content herself with that; it was enough of a gift from life.

'I'll come and see you,' said Ralf Hart.

'No, don't. I'll be going back to Brazil soon. We have nothing more to give each other.'

'I'll come and see you as a client.'

'That would be humiliating for me.'

'I'll come and see you so that you can save me.'

He had made that comment early on, about his lack of interest in sex. She wanted to tell him that she felt the same, but she stopped herself - she had said 'no' too many times; it would be best to say nothing.

How pathetic. There she was with the little boy again, only he wasn't asking her for a pencil now, just a little company. She looked at her own past, and, for the first time, she forgave herself: it hadn't been her fault, but the fault of that insecure little boy, who had given up after the first attempt. They were children and that's how children are - neither she nor the boy had been in the wrong, and that gave her a great sense of relief, made her feel better;

she hadn't betrayed the first opportunity that life had presented her with. We all do the same thing: it's part of the initiation of every human being in search of his or her other half; these things happen.

Now, though, the situation was different. However convincing her reasons (I'm going back to Brazil, I work in a nightclub, we hardly know each other, I'm not interested in sex, I don't want anything to do with love, I need to learn how to manage a farm, I don't understand painting, we live in different worlds), life had thrown down a challenge. She wasn't a child any more, she had to choose.

She preferred to say nothing. She shook his hand, as was the custom there, and went home. If he was the man she wanted him to be, he would not be intimidated by her silence.

Extract from Maria's diary, written that same day:

Today, while we were walking around the lake, along that strange road to Santiago, the man who was with me - a painter, with a life entirely different from mine - threw a pebble into the water. Small circles appeared where the pebble fell, which grew and grew until they touched a duck that happened to be passing and which had nothing to do with the pebble. Instead of being afraid of that unexpected wave, he decided to play with it.

Some hours before that scene, I went into a cafe, heard a voice, and it was as if God had thrown a pebble into that place. The waves of energy touched both me and a man sitting in a corner painting a portrait. He felt the vibrations of that pebble, and so did I. So what now?

The painter knows when he has found a model. The musician knows when his instrument is well tuned. Here, in my diary, I am aware that there are certain phrases which are not written by me, but by a woman full of 'light'-, I am that woman though I refuse to accept it.

I could carry on like this, but I could also, like the duck on the lake, have fun and take pleasure in that sudden ripple that set the water rocking.

There is a name for that pebble: passion. It can be used to describe the beauty of an earth-shaking meeting between two people, but it isn't just that. It's there in the excitement of the unexpected, in the desire to do something with real fervour, in the certainty that one is going to realise a dream. Passion sends us signals that guide us through our lives, and it's up to me to interpret those signs.

I would like to believe that I'm in love. With someone I don't know and who didn't figure in my plans at all. All these months of self-control, of denying love, have had exactly the opposite result: I have let myself be swept away by the first person to treat me a little differently. It's just as well I don't have his phone number, that I don't know where he lives; that way I can lose him without having to blame myself for another missed opportunity.

And if that is what happens, if I have already lost him, I will at least have gained one very happy day in my life. Considering the way the world is, one happy day is almost a miracle.

When she arrived at the Copacabana that night, he was there, waiting for her. He was the only customer. Milan, who had been following her life with some interest, saw that she had lost the battle.

'Would you like a drink?' the man asked.

'I have to work. I can't risk losing my job.'

'I'm here as a customer. I'm making a professional proposition.'

This man, who had seemed so sure of himself that afternoon in the cafe, who wielded a paintbrush with such skill, met important people, had an agent in Barcelona and doubtless earned a lot of money, was now revealing his fragility; he had entered a world he should not have entered; he was no longer in a romantic cafe on the road to Santiago. The charm of the afternoon vanished.

'So, would you like a drink?'

I will another time. I have clients waiting for me tonight.'

Milan overheard these last words; he was wrong, she had not allowed herself to be caught in the trap of promises of love. He nevertheless wondered, at the end of a rather slack night, why she had preferred the company of an old man, a dull accountant and an insurance salesman ...

Oh, well, it was her problem. As long as she paid her commission, it wasn't up to him to decide who she should or shouldn't go to bed with.

From Maria's diary, after that night with the old man, the accountant and the insurance salesman:

What does this painter want of me? Doesn't he realise that we are from different countries, cultures and sexes? Does he think I know more about pleasure than he does and wants to learn something from me?

Why didn't he say anything else to me, apart from 'I'm here as a customer'? It would have been so easy for him to say: 'I missed you' or really enjoyed the afternoon we spent together'. I would respond in the same way (I'm a professional), but he should understand my insecurities, because I'm a woman, I'm fragile, and when I'm in that place, I'm a different person.

He's a man. He's an artist. He should know that the great aim of every human being is to understand the meaning of total love. Love is not to be found in someone else, but in ourselves; we simply awaken it. But in order to do that, we need the other person. The universe only makes sense when we have someone to share our feelings with.

He says he's tired of sex. So am I, and yet neither of us really knows what that means. We are allowing one of the most important things in life to die - he should have saved me, I should have saved him, but he left me no choice.

L She was terrified. She was beginning to realise that after long months of self-control, the pressure, the earthquake, the volcano of her soul was showing signs that it was about to erupt, and the moment that this happened, she would have no way of controlling her feelings. Who was this wretched painter, who might well be lying about his life and with whom she had spent only a few hours, who had not touched her or tried to seduce her - could there be anything worse?

Why were alarm bells ringing in her heart? Because she sensed that the same thing was happening to him, but no, she must be wrong. Ralf Hart just wanted to find a woman capable of awakening in him the fire that had almost burned out; he wanted to make her into some kind of personal sex goddess, with her 'special light' (he was being honest about that), who would take him by the hand and show him the road back to life. He couldn't imagine that Maria felt the same indifference, that she had her own problems (even after so many men, she had still never achieved orgasm when having ordinary penetrative sex), that she had been making plans that very morning and was organising a triumphant return to her homeland.

Why was she thinking about him? Why was she thinklng about someone who, at that very moment, might be painting another woman, saying that she had a 'special light', that she could be his sex goddess?

'I'm thinking about him because I was able to talk to him.'

How ridiculous! Did she think about the librarian? No. Did she think about Nyah, the Filipino girl, the only one of all the women who worked at the Copacabana with whom she could share some of her feelings? No, she didn't. And they were people with whom she had often talked and with whom she felt comfortable.

She tried to divert her attention to thoughts of how hot it was, or to the supermarket she hadn't managed to get to yesterday. She wrote a long letter to her father, full of details about the piece of land she would like to buy - that would make her family happy. She did not give a date for her return, but she hinted that it would be soon. She slept, woke up, slept again and woke again. She realised that the book about farming was fine for Swiss farmers, but completely useless for Brazilians - they were two entirely different worlds.

As the afternoon wore on, she noticed that the earthquake, the volcano, the pressure was diminishing. She felt more relaxed; this kind of sudden passion had happened before and had always subsided by the next day - good, her universe continued unchanged. She had a family who loved her, a man who was waiting for her and who now wrote to her frequently, telling her that the draper's shop was expanding. Even if she decided to get on a plane that night, she had enough money to buy a small farm. She had got through the worst part, the language barrier, the loneliness, the first night in the restaurant with that Arab man, the way in which she had persuaded her soul not to complain about what she was doing with her body. She knew what her dream was and she was prepared to do anything to achieve it. And that dream did not, by the way, include men, at least not men who didn't speak her mother tongue or live in her hometown.

When the earthquake had subsided, Maria realised she was partly to blame. Why had she not said to him: 'I'm lonely, I'm as miserable as you are, yesterday you saw my “light”, and it was the first nice, honest thing a man has said to me since I got here.'

On the radio they were playing an old song: 'my loves die even before they're born'. Yes, that was what happened with her, that was her fate.

From Maria's diary, two days after everything had returned to normal:

Passion makes a person stop eating, sleeping, working, feeling at peace. A lot of people are frightened because, when it appears, it demolishes all the old things it finds in its path.

No one wants their life thrown into chaos. That is why a lot of people keep that threat under control, and are somehow capable of sustaining a house or a structure that is already rotten. They are the engineers of the superseded.

Other people think exactly the opposite: they surrender themselves without a second thought, hoping to find in passion the solutions to all their problems. They make the other person responsible for their happiness and blame them for their possible unhappiness. They are either euphoric because something marvellous has happened or depressed because something unexpected has just ruined everything. Keeping passion at bay or surrendering blindly to it -

which of these two attitudes is the least destructive?

I don't know.

On the third day, as if risen from the dead, Ralf Hart returned, almost too late, for Maria was already talking to another customer. When she saw him, though, she politely told the other man that she didn't want to dance, that she was waiting for someone else.

Only then did she realise that she had spent the last three days waiting for him. And at that moment, she accepted everything that fate had placed in her path.

She didn't get angry with herself; she was happy, she could allow herself that luxury, because one day she would leave this city; she knew this love was impossible, and yet, expecting nothing, she could nevertheless have everything she still hoped for from that particular stage in her life.

Ralf asked her if she would like a drink, and Maria asked for a fruit juice cocktail. The owner of the bar, pretending that he was washing glasses, stared uncomprehendingly at her: what had made her change her mind? He hoped they wouldn't just sit there drinking, and felt relieved when Ralf asked her to dance. They were following the ritual; there was no reason to feel worried.

Maria felt Ralf's hand on her waist, his cheek pressed to hers, and the music - thank God - was too loud for them to talk. One fruit juice cocktail wasn't enough to give her courage, and the few words they had exchanged had been very formal. Now it was just a question of time: would they go to a hotel? Would they make love? It shouldn't be difficult, since he had already said that he wasn't interested in sex - it would just be a matter of going through the motions. On the other hand, that lack of interest would help to kill off any vestige of potential passion - she didn't know now why she had put herself through such torment after their first meeting.

Tonight she would be the Understanding Mother. Ralf Hart was just another desperate man, like millions of others. If she played her role well, if she managed to follow the rules she had laid down for herself since she began working at the Copacabana, there was no reason to worry. It was very dangerous, though, having that man so near, now that she could smell him - and she liked the way he smelled - now that she could feel his touch - and she liked his touch - now that she realised she had been waiting for him - she did not like that.

Within forty-five minutes they had fulfilled all the rules, and the man went over to the owner of the bar and said:

'I'm going to spend the rest of the night with her. I'll pay you as if I were three clients.'

The owner shrugged and thought again that the Brazilian girl would end up falling into the trap of love. Maria, for her part, was surprised: she hadn't realised that Ralf Hart knew the rules so well.

'Let's go back to my house.'

Perhaps that was the best thing to do, she thought.

Although it went against all of Milan's advice, she decided, in this case, to make an exception. Apart from finding out once and for all whether or not he was married, she would also find out how famous painters live, and one day she would be able to write an article for her local newspaper, so that everyone would know that, during her time in Europe, she had moved in intellectual and artistic circles.

'What an absurd excuse!' she thought.

Half an hour later, they arrived at a small village near Geneva, called Cologny; there was a church, a bakery, a town hall, everything in its proper place. And he really did live in a two-storey house, not an apartment! First reaction: he really must be rich. Second reaction: if he were married, he wouldn't dare to do this, because they would be bound to be seen by someone.

So, he was rich and single.

They went into a hall from which a staircase ascended to the second floor, but they went straight ahead to the two rooms at the back that looked onto the garden. There was a dining table in one of the rooms, and the walls were crowded with paintings. In the other room were sofas and chairs, packed bookshelves, overflowing ashtrays and dirty glasses that had clearly been there for a long time.

'Would you like a coffee?'

Maria shook her head. No, she wouldn't. You can't treat me differently just yet. I'm confronting my own demons, doing exactly the opposite of what I promised myself I would do. But let's take things slowly; tonight I'll play the part of prostitute or friend or Understanding Mother, even though in my soul I'm a Daughter in need of affection. When it's all over, then you can make me a coffee.

'At the bottom of the garden is my studio, my soul. Here, amongst all these paintings and books, is my brain, what I think.'

Maria thought of her own apartment. She had no garden at the back. She did not even have any books, apart from those she borrowed from the library, since there was no point in spending money on something she could get for free. There were no paintings either, apart from a poster for the Shanghai Acrobatic Circus, which she dreamed of going to one day.

Ralf picked up a bottle of whisky and offered her a glass.

'No, thank you.'

He poured himself a drink and swallowed it down in one - without ice, without time to savour it. He started talking about intelligent things, but, however interesting the conversation, she knew that he too was afraid of what was going to happen, now that they were alone. Maria had regained control of the situation.

Ralf poured himself another whisky and, as if he were making some utterly inconsequential remark, he said:

'I need you.'

A pause. A long silence. Don't help to break that silence, let's see what he does next.

'I need you, Maria. Because you have a light, although I don't really think you believe me yet, and think I'm just trying to seduce you with my words. Don't ask me: "Why me?

What's so special about me?" There isn't anything special about you, at least, nothing I can put my finger on. And yet and here's the mystery of life - I can't think of anything else.'

'I wasn't going to ask you,' she lied.

'If I were looking for an explanation, I would say: the woman in front of me has managed to overcome suffering and to transform it into something positive, something creative, but that doesn't explain everything.'

It was becoming difficult to escape. He went on:

'And what about me? I have my creativity, I have my paintings, which are sought after by galleries all over the world, I have realised my dream, my village thinks of me as a beloved son, my ex-wives never ask me for alimony or anything like that, I have good health, reasonable looks, everything a man could want ... And yet here I am saying to a woman I met in a cafe and with whom I have spent one afternoon: “I need you.” Do you know what loneliness is?'

'I do.'

'But you don't know what loneliness is like when you have the chance to be with other people all the time, when you get invitations every night to parties, cocktail parties, opening nights at the theatre ... When women are always ringing you up, women who love your work, who say how much they would like to have supper with you - they're beautiful, intelligent, educated women. But something pushes you away and says: “Don't go. You won't enjoy yourself. You'll spend the whole night trying to impress them and squander your energies proving to yourself how you can charm the whole world.”

'So I stay at home, go into my studio and try to find the light I saw in you, and I can only see that light when I'm working.'

'What can I give you that you don't already have?' she asked, feeling slightly humiliated by that remark about other women, but remembering that he had, after all, paid to have her at his side.

He drank a third glass of whisky. Maria accompanied him in her imagination, the alcohol burning his throat and his stomach, entering his bloodstream and filling him with courage, and she too began to feel drunk, even though she hadn't touched a drop. When Ralf spoke again, his voice sounded steadier:

'I can't buy your love, but you did tell me that you knew everything about sex. Teach me, then. Or teach me something about Brazil. Anything, just as long as I can be with you.' What next?

'I only know two places in my own country: the town I was born in and Rio de Janeiro. As for sex, I don't think I can teach you anything. I'm nearly twenty-three, you're about six years older, but I know you've lived life very intensely. I know men who pay me to do what they want, not what I want.'

'I've done everything a man could dream of doing with one, two, even three women at the same time. And I don t think I learned very much.'

Silence again, except that this time it was Maria's turn to speak. And he did not help her, just as she had not helped him before.

'Do you want me as a professional?' 'I want you however you want to be wanted.' No, he couldn't have said that, because that was precisely what she had wanted to hear.

The earthquake, the volcano, the storm returned. It was going to be impossible to escape her own trap, she would lose this man without ever really having him.

'You know what I mean, Maria. Teach me. Perhaps that will save me, perhaps it will save you and bring us both back to life. You're right, I am only six years older than you, and yet I've lived enough for several lives. Our experiences have been entirely different, but we are both desperate people;

the only thing that brings us any peace is being together.' Why was he saying these things? It wasn't possible, and yet it was true. They had only met once before and yet they already needed each other. Imagine what would happen if they continued seeing each other; it would be disastrous! Maria was an intelligent woman, with many months behind her now of reading and of observing humankind;

she had an aim in life, but she also had a soul, which she needed to know in order to discover her 'light'. She was becoming tired of being who she was, and although her imminent return to Brazil was an interesting challenge, she had not yet learned all she could. Ralf Hart was a man who ad accepted challenges and had learned everything, and n°w he was asking this woman, this prostitute, this nderstanding Mother, to save him. How absurd!

Other men had behaved like this with her. Many of them had been unable to have an erection, others had wanted to be treated like children, others had said that they would like her to be their wife because it excited them to know that she had had so many lovers. Although she had still not met any of the 'special clients', she had already discovered the vast universe of fantasies that fills the human soul. But they were all used to their own worlds and none of them had said to her: 'take me away from here'. On the contrary, they wanted to take Maria with them.

And even though those many men had always left her with money, but drained of energy, she must have learned something. If one of them had really been looking for love, and if sex really was only part of that search, how would she like to be treated? What did she think should happen on a first meeting?

What would she really like to happen?

'I'd like a gift,' said Maria.

Ralf Hart didn't understand. A gift? He had already paid for that night in advance, while they were in the taxi, because he knew the ritual. What did she mean?

Maria had suddenly realised that she knew, at that moment, what a man and a woman needed to feel. She took his hand and led him into one of the sitting rooms.

'We won't go up to the bedroom,' she said.

She turned out almost all the lights, sat down on the carpet and asked him to sit down opposite her. She noticed that there was a fire in the room.

'Light the fire.'

'But it's summer.'

'Light the fire. You asked me to guide our steps tonight and that's what I'm doing.'

She gave him a steady look, hoping that he would again see her 'light'. He obviously did, because he went out into the garden, collected some wood still wet with rain, and picked up some old newspapers so that the fire would dry the wood and get it to burn. He went into the kitchen to fetch more whisky, but Maria called him back.

'Did you ask me what I wanted?'

'No, I didn't.'

'Well, the person you're with has to exist too. Think of her. Think if she wants whisky or gin or coffee. Ask her what she wants.'

'What would you like to drink.'

'Wine. And I'd like you to keep me company.'

He put down the whisky bottle and returned with a bottle of wine. By this time, the fire was already beginning to burn; Maria turned out the few remaining lights, so that the flames were the only illumination in the room. She behaved as if she had always known that this was the first step: recognising the other person and knowing that he or she was there.

She opened her handbag and found inside a pen she had bought in a supermarket. Anything would do.

'This is for you. I bought it so that I could note down some ideas about farm management. I used it for two days, I worked until I was too tired to work any more. It contains some of my sweat, some of my concentration and my willpower, and I'm giving it to you now.'

She placed the pen gently in his hand.

'Instead of buying something that you would like to have, I'm giving you something that is mine, truly mine. A gift. A sign of respect for the person before me, asking him to understand how important it is to be by his side. Now he has a small part of me with him, which I gave him with my free, spontaneous will.'

Ralf got up, went over to a shelf and returned, carrying something. He held it out to Maria.

'This is a carriage belonging to an electric train set I had when I was a child. I wasn't allowed to play with it on my own, because my father said it had been imported from the United States and was very expensive. So I had to wait until he felt like setting up the train in the living room, but he spent most Sundays listening to opera. That's why the train survived my childhood, but never gave me any happiness. I've still got all the track, the engine, the houses, even the manual, because I had a train that wasn't mine and with which I never played.

'I wish I'd destroyed it along with all the other toys I was given and which I've since forgotten all about, because that passion for destruction is part of how a child discovers the world. But this pristine train set always reminds me of a part of my childhood that I never lived, because it was too precious and it meant too much work for my father. Or perhaps it was just that whenever he set the train up, he was afraid he might show his love for me.'

Maria began staring into the fire. Something was happening, and it wasn't just the wine or the cosy atmosphere. It was that exchange of gifts.

Ralf turned to the fire too. They said nothing, listening to the crackle of the flames. They drank their wine, as if it didn't matter that they said nothing, did nothing. They were just there, together, staring in the same direction.

'I have a lot of pristine train sets in my life too,' said Maria, after a while. 'One of them is my heart. And I only played with it when the world set out the tracks, and then it wasn't always the right moment.'

'But you loved.'

'Oh, yes, I loved, I loved very deeply. I loved so deeply that when my love asked me for a gift, I took fright and fled.'

'I don't understand.'

'You don't have to. I'm teaching you because I've discovered something I didn't know before. The giving of gifts. Giving something of one's own. Giving something important rather than asking. You have my treasure: the pen with which I wrote down some of my dreams. I have your treasure: the carriage of a train, part of your childhood that you did not live.

'I carry with me part of your past, and you carry with you a little of my present. Isn't that lovely?'

She said all this without blinking, and without surprise, as if she had known for ages that this was the best and only way to behave. She got lightly to her feet, took her jacket from the coat rack and kissed Ralf on the cheek. Ralf Hart did not make any move to get up, hypnotised by the fire, Perhaps thinking about his father.

'I never understood why I kept that carriage. Now I do:

it was in order to give it to you one night before an open fire. Now the house feels lighter.'

He said that the next day he would give the rest of the tracks, engines, smoke pills, to some children's home.

'It could be a rarity, of a kind that isn't made any more;

it could be worth a lot of money,' said Maria, but immediately regretted her words. That wasn't what mattered, the point was to free yourself from something that cost your heart even more.

Before she said anything else that did not quite chime with the moment, she again kissed him on the cheek and walked to the front door. He was still gazing into the fire, and she had to ask him softly if he would open the door for her.

Ralf got up, and she explained that, although she was glad to see him staring into the fire, Brazilians have a strange superstition: when you visit someone for the first time, you must not be the one to open the door when you leave, because if you do, you will never return to that house.

'And I want to come back.'

'Although we didn't take our clothes off and I didn't come inside you, or even touch you, we've made love.'

She laughed. He offered to take her home, but she refused.

'I'll come and see you tomorrow, then, at the Copacabana.'

'No, don't. Wait a week. I've learned that waiting is the most difficult bit, and I want to get used to the feeling, knowing that you're with me, even when you're not by my side.'

She walked back through the cold and the dark, as she had so many times before in Geneva; normally, these walks were associated with sadness, loneliness, the desire to go back to Brazil, financial calculations, timetables, nostalgia for the language she hadn't spoken freely for ages.

Now, though, she was walking in order to find herself, to find that woman who had sat with a man by a fire for forty minutes and who was full of light, wisdom, experience and charm. She had seen that woman's face a long time ago, when she was walking by the lakeside wondering whether or not she should devote herself to a life that wasn't hers - on that afternoon, the woman had a terribly sad smile on her face. She had seen her for a second time on that folded canvas, and now she was with her again. She only caught a taxi after she had walked quite a way, when the magic presence had gone, leaving her alone again, as usual.

It was best not to think too much about it all, so as not to spoil it, so as not to let the beauty of what she had just experienced be replaced by anxiety. If that other Maria really existed, she would return when the moment was right.

An extract from the diary Maria wrote on the night she was given the train carriage: i J Profound desire, true desire is the desire to be close to someone. From that point onwards, things change, fl the man and the woman come into play, but what m 1 happens before - the attraction that brought them % together - is impossible to explain. It is untouched desire in its purest state.

When desire is still in this pure state, the man and the woman fall in love with life, they live each moment reverently, consciously, always ready to celebrate the next blessing.

When people feel like this, they are not in a hurry, they do not precipitate events with unthinking actions. They know that the inevitable will happen, that what is real always finds a way of revealing itself. When the moment comes, they do not hesitate, they do not miss an opportunity, they do not let slip a single magic moment, because they respect the importance of each second.

ift In the days that followed, Maria found herself once more caught in the trap she had tried so hard to avoid, but she felt neither sad nor concerned. On the contrary, now that she had nothing to lose, she was free.

She knew that, however romantic the situation, one day, Ralf Hart would realise that she was just a prostitute, while he was a respected artist, that she lived in a far-off country that was in a state of permanent crisis, while he lived in paradise, with his life organised and protected from birth. He had received his education in the best schools, museums and art galleries of the world, while she had barely finished secondary school. Dreams like theirs never lasted long, and Maria had enough experience of life to know that reality usually chose not to fit in with her dreams. And that was now her great joy: to say to reality that she didn't need it, that she was no longer dependent on what happened in order to be happy.

'God, I'm such a romantic'

During the week, she tried to think of something that would make Ralf Hart happy; for he had restored to her a dignity and a 'light' that she thought were lost forever. But The only way she had of repaying him was with the thing he thought was her speciality: sex. Since there was little to inspire her in the routine at the Copacabana, she decided to look elsewhere.

She again went to see a few porn movies, and again found nothing of interest in them, apart, perhaps, from the varying number of people involved. When films proved of no help, she decided, for the first time since she had arrived in Geneva, to buy some books, although she still didn't see the point in cluttering up her apartment with something which, once read, had no further use. She went to the bookshop she had seen when she and Ralf had walked down the road to Santiago, and asked if they had any books about sex.

'Oh, loads,' said the shop assistant. 'In fact, it seems to be all people care about. There's a special section devoted to the subject, but in just about every other novel you can see around you there's always at least one sex scene. Whether it's hidden away in pretty little love stories or discussed in serious tomes on human behaviour, it appears to be all anyone thinks about.'

Maria, with all her experience, knew that the woman was wrong: people wanted to think like that because they thought sex was everyone else's sole concern. They went on diets, wore wigs, spent hours at the hairdresser's or at the gym, put on sexy clothes, all in an attempt to awaken the necessary spark. And what happened? When the moment came to go to bed with someone, eleven minutes later it was all over. There was no creativity involved, nothing that would lift them up to paradise; the fire provoked by the spark soon burned out.

But there was no point arguing with the young blonde woman, who believed that the world could be explained in books. She asked to be directed to the special section, and there she found various books about gay men, lesbians, nuns revealing scandals in the church, illustrated books showing oriental techniques, all involving extremely uncomfortable positions, but only one of the titles interested her: Sacred Sex. At least it was different.

She bought it, went home, tuned to a particular radio station that always helped her to think (because they played such calming music), opened the book and noticed various illustrations, showing postures that only a circus performer could possibly hope to achieve. The text itself was very dull.

Maria had learned enough in her profession to know that not everything in life is a matter of what position you adopt when making love, and that any variation usually occurs naturally, without thinking, like the steps in a dance. Nevertheless, she tried to concentrate on what she was reading.

Two hours later, she had come to two conclusions.

First, she needed to eat supper, because she had to get back to the Copacabana.

Second, the person who had written the book clearly understood nothing, absolutely nothing about the subject. It was just a lot of empty theory, oriental nonsense, pointless rituals and idiotic suggestions. She noticed that the author had studied meditation in the Himalayas (she must find out where they were), attended courses in yoga (she had heard of that), and had obviously read widely in the subject, for she kept quoting other authors, but she had failed to learn what was essential. Sex wasn't theories, incense, erogenous zones, bows and salaams. How did that person (a woman) have the nerve to write on a subject which not even Maria, who worked in the field, knew in depth.

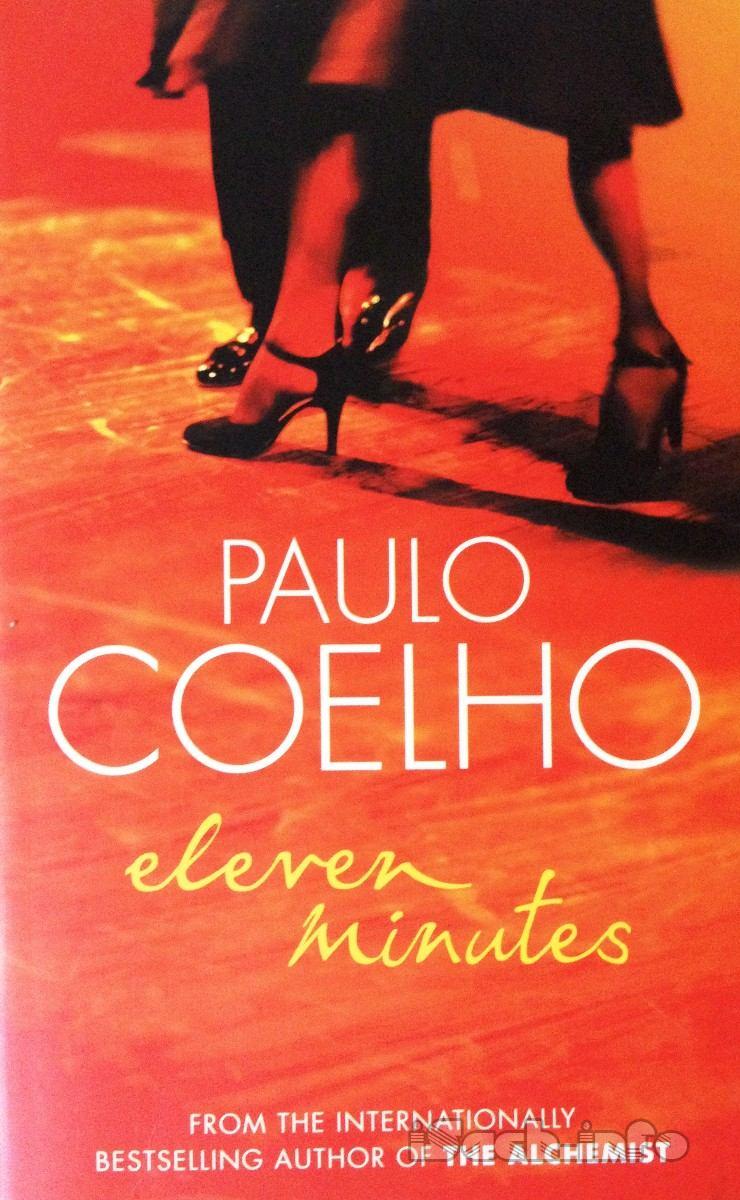

Perhaps it was all the fault of the Himalayas or the need to complicate something whose very beauty lay in simplicity and passion. If that woman could get away with publishing and selling such a stupid book, perhaps she should think seriously again about writing her own: Eleven Minutes. It wouldn't be cynical or false - it would just be her story. But she had neither the time nor the interest; she needed to focus her energies on making Ralf Hart happy and on learning how to manage a farm.

From Maria's diary, just after abandoning the boring book: I've met a man and fallen in love with him. I allowed myself to fall in love for one simple reason: I'm not expecting anything to come of it. I know that, in three months' time, I'll be far away and he'll be just a memory, but I couldn't stand living without love any longer; I had reached my limit.

I'm writing a story for Ralf Hart - that's his name. I'm not sure he'll come back to the club where I work, but, for the first time in my life, that doesn't matter. It's enough just to love him, to be with him in my thoughts and to colour this lovely city with his steps, his words, his love. When I leave this country, it will have a face and a name and the memory of a fireplace. Everything else I experienced here, all the difficulties I had to overcome, will be as nothing compared to that memory.

I would like to do for him what he did for me. I've been thinking about it a lot, and I realise that I didn't go into that cafe by chance; really important meetings are planned by the souls long before the bodies see each other.

Generally speaking, these meetings occur when we reach a limit, when we need to die and be reborn emotionally. These meetings are waiting for us, but more often than not, we avoid them happening. If we are desperate, though, if we have nothing to lose, or if we are full of enthusiasm for life, then the unknown reveals itself, and our universe changes direction.

Everyone knows how to love, because we are all born with that gift. Some people have a natural talent for it, but the majority of us have to re-learn, to remember how to love, and everyone, without exception, needs to burn on the bonfire of past emotions, to relive certain joys and griefs, certain ups and downs, until they can see the connecting thread that exists behind each new encounter; because there is a connecting thread.

And then, our bodies learn to speak the language of the soul, known as sex, and that is what I can give to the man who gave me back my soul, even though he has no idea how important he is to my life. That is what he asked me for and that is what he will have; I want him to be very happy.

Sometimes life is very mean: a person can spend days, weeks, months and years without feeling anything new. Then, when a door opens - as happened with Maria when she met Ralf Hart - a positive avalanche pours in. One moment, you have nothing, the next, you have more than you can cope with.

Two hours after writing her diary, when she arrived at work, Milan, the owner, came looking for her:

'So you went out with that painter, did you?'

Ralf was obviously known at the club - she had realised this when he paid the rate for three customers, without having to ask the price. Maria merely nodded, trying to act mysterious, but Milan took no notice; he knew this life better than she did.

'Perhaps you're ready for the next stage. There's a special client of ours who has often asked about you. I told him that you're not experienced enough, and he believed me, but perhaps now is the moment to try.'

A special client?

'What's this got to do with the painter?'

'He's a special client too.'

So everything she had done with Ralf Hart had already been done by one of her colleagues. She bit her lip and said nothing; she had had a lovely week, and she must not forget what she had written.

'Should I do the same thing I did with him?'

'I don't know what you did; but tonight, if someone offers you a drink, say no. Special clients pay more; you won't regret it.'

Work started as it always did. The Thai women all sat together, the Colombians adopted their usual air of knowing everything, the three Brazilians (including her) looked absently about them, as if nothing could ever surprise or interest them. Apart from them, there was an Austrian, two Germans, and the rest were tall, pretty women with pale eyes who came from the former Eastern Bloc countries and who always seemed to find husbands more quickly than the others. The men began to arrive - Russian, Swiss, German, all of them busy executives, well able to afford the services of the most expensive prostitutes in one of the most expensive cities in the world. Some came over to her table, but she kept her eye on Milan, who shook his head. Maria was pleased;

tonight, she wouldn't have to open her legs, put up with smells or take showers in sometimes chilly bathrooms; all she had to do was to teach a man grown weary of sex how to make love. And when she thought about it, not every woman would have been creative enough to come up with that story about the exchange of gifts.

At the same time, she was wondering: Why is it that, having experienced everything, these men want to go right back to the start? Not that this was her concern; as long as they paid well, she was there to serve them.

A man came in, younger than Ralf Hart; he was goodlooking, with dark hair, perfect teeth, and wearing what looked like a Mao jacket - no tie, just a high collar and, underneath, an impeccable white shirt. He went up to the bar, where both he and Milan turned to look at Maria; then he came over.

'Would you like a drink?'

She saw Milan nod, and so invited the man to sit down at her table. She ordered a fruit juice cocktail and waited for him to ask her to dance. Then the man introduced himself:

'My name is Terence, and I work for a record company in England. Since I assume I'm in a place where I can trust the personnel, I take it this will remain entirely between you and me.'

Maria was about to start talking about Brazil, but he interrupted her:

'Milan says you understand what I want.'

'I've no idea what you want, but I know my job.'

They did not follow the usual ritual; he paid the bill, took her arm and they got into a taxi, where he gave her a thousand francs. For a moment, she remembered the Arab man with whom she had gone to the restaurant full of famous paintings; it was the first time she had received the same amount of money, and instead of making her feel glad, it made her feel nervous.

The taxi stopped outside one of the most expensive hotels in the city. The man greeted the porter and seemed totally at ease in the place. They went straight up to his room, a suite with a view over the river. He opened a bottle of wine - possibly a rare vintage - and offered her a glass.

Maria watched him while he drank; what did a rich, good-looking man like him want with a prostitute? Since he barely spoke, she too remained largely silent, trying to work out what would make a special client happy. She knew that she should not take the initiative, but once the process had begun, she needed to be able to follow his lead as quickly as possible; after all, it wasn't every night that she earned a thousand francs.

'We've got plenty of time,' Terence said. 'All the time in the world. You can sleep here if you like.'

Her feelings of insecurity returned. The man did not seem in the least intimidated, and, unlike her other customers, he spoke very calmly. He knew what he wanted; he put on the perfect piece of music, at the perfect volume, in the perfect room, with the perfect window, which looked out onto the lake of a perfect city. His suit was welltailored, his suitcase was there in the corner, very small, as if he always travelled light, or as if he had come to Geneva just for that one night.

'I'll sleep at home,' Maria said.

The man opposite her changed completely. An icy glint came into his hitherto gentlemanly eyes.

'Sit there,' he said, indicating a chair by the desk.

It was an order! A real order. Maria obeyed and, oddly enough, she felt excited.

'Sit properly. Back straight, like a lady. If you don't, I'll punish you.'

Punish her! Special client! In a flash, she understood everything, took the thousand francs out of her bag and put it down on the desk.

'I know what you want,' she said, looking deep into those cold, blue eyes. 'And I won't do it.'

The man seemed to return to his normal self and he could see that she was telling the truth.

'Have a drink of wine,' he said. 'I won't force you to do anything. You can either stay a little longer, if you like, or you can leave.'

That made her feel better.

'I have a job. I have a boss who protects and trusts me. I'd be grateful if you didn't say anything to him.'

Maria said this without a hint of pleading or self-pity in her voice; it was simply how things were.

Terence was once again the man she had first met neither gentle nor harsh, just someone who, unlike her other clients, gave the impression that he knew what he wanted. He seemed to emerge from a trance, from a play that had scarcely begun.

Was it worth leaving now and never finding out the truth about this 'special client'?

'What exactly did you want?'

'You know what I want. Pain. Suffering. And a great deal of pleasure.'

'Pain and suffering don't normally go with pleasure,'

Maria thought. And yet she desperately wanted to believe that they did, and thus make a positive out of her many negative experiences.

He took her by the hand and led her over to the window: on the other side of the lake they could see a cathedral spire. Maria remembered passing it when she had walked the road to Santiago with Ralf Hart.

'You see the river, the lake, the houses and the church?

Well, it was all pretty much the same five hundred years ago, except that the city was deserted. A strange disease had spread throughout Europe, and no one knew why so many people were dying. They began to call the disease the Black Death - sent by God because of mankind's sins.

'Then a group of people decided to sacrifice themselves for the sake of humanity. They offered the thing they most feared: physical pain. They began to spend days and nights walking across these bridges, along these streets, beating their own bodies with whips and chains. They were suffering in the name of God and praising God with their pain. They soon realised that they were happier doing this than baking bread, working in the fields or feeding their animals. Pain was no longer a cause of suffering, but a source of pleasure because they were redeeming humanity from its sins. Pain became joy, the meaning of life, pleasure.'

ePub

ePub A4

A4