Chapter Two

5

Little girl in red stretch pants and a green rayon blouse. Shoulder-length blond hair. Up too late, apparently by herself. She was in one of the few places where a little girl by herself could go unremarked after midnight. She passed people, but no one really saw her. If she had been crying, a security guard might have come over to ask her if she was lost, if she knew which airline her mommy and daddy were ticketed on, what their names were so they could be paged. But she wasn't crying, and she looked as if she knew where she was going.

She didn't exactly-but she had a pretty fair idea of what she was looking for. They needed money; that was what Daddy had said. The bad men were coming, and Daddy was hurt. When he got hurt like this, it got hard for him to think. He had to lie down and have as much quiet as he could. He had to sleep until the pain went away. And the bad men might be coming... the men from the Shop, the men who wanted to pick them apart and see what made them work-and to see if they could be used, made to do things.

She saw a paper shopping bag sticking out of the top of a trash basket and took it. A little way farther down the concourse she came to what she was looking for: a bank of pay phones.

Charlie stood looking at them, and she was afraid. She was afraid because Daddy had told her again and again that she shouldn't do it... since earliest childhood it had been the Bad Thing. She couldn't always control the Bad Thing. She might hurt herself, or someone else, or lots of people. The time

(oh mommy I'm sorry the hurt the bandages the screams she screamed i made my mommy scream and i never will again... never... because it is a Bad Thing) in the kitchen when she was little... but it hurt too much to think of that. It was a Bad Thing because when you let it go, it went... everywhere. And that was scary.

There were other things. The push, for instance; that's what Daddy called it, the push.

Only she could push a lot harder than Daddy, and she never got headaches afterward. But sometimes, afterward... there were fires.

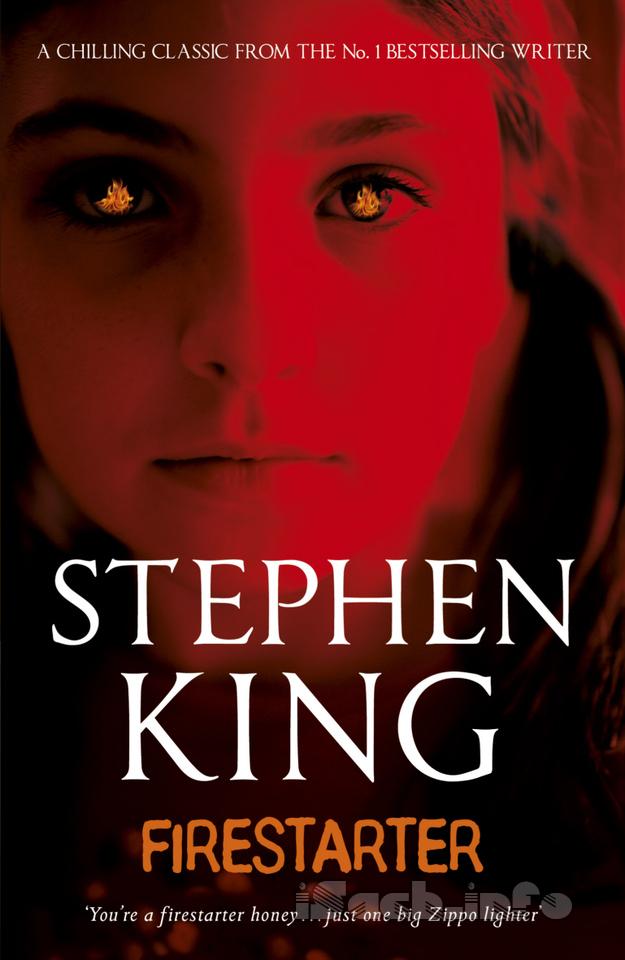

The word for the Bad Thing clanged in her mind as she stood nervously looking at the telephone booths: pyrokinesis "Never mind that," Daddy had told her when they were still in Port City and thinking like fools that they were safe. "You're a firestarter, honey. Just one great big Zippo lighter." And then it had seemed funny, she had giggled, but now it didn't seem funny at all.

The other reason she wasn't supposed to push was because they might find out. The bad men from the Shop. "I don't know how much they know about you now," Daddy had told her, "but I don't want them to find out anymore. Your push isn't exactly like mine, honey. You can't make people... well, change their minds, can you?"

"No-ooo..." "But you can make things move. And if they ever began to see a pattern, and connect that pattern with you, we'd be in even worse trouble than we are now."

And it was stealing, and stealing was also a Bad Thing.

Never mind. Daddy's head was hurting him and they had to get to a quiet, warm place before it got too bad for him to think at all. Charlie moved forward.

There were about fifteen phonebooths in all, with circular sliding doors. When you were inside the booth, it was like being inside a great big Contac capsule with a phone inside it. Most of the booths were dark, Charlie saw as she drifted down past them. There was a fat lady in a pantsuit crammed into one of them, talking busily and smiling. And three booths from the end a young man in a service uniform was sitting on the little stool with the door open and his legs poking out. He was talking fast.

"Sally, look, I understand how you feel, but I can explain everything. Absolutely. I know... I know... but if you'll just let me-"He looked up, saw the little girl looking at him, and yanked his legs in and pulled the circular door closed, all in one motion, like a turtle pulling into its shell. Having a fight with his girlfriend, Charlie thought. Probably stood her up. I'd never let a guy stand me up.

Echoing loudspeaker. Rat of fear in the back of her mind, gnawing. All the faces were strange faces.

She felt lonely and very small, grief-sick over her mother even now. This was stealing, but what did it matter? They had stolen her mother's life.

She slipped into the phonebooth on the end, shopping bag crackling. She took the phone off the hook and pretended she was talking-hello, Grampa, yes, Daddy and I just got in, we're fine-and looked out through the glass to see if anyone was being nosy. No one was. The only person nearby was a black woman getting flight insurance from a machine, and her back was to Charlie.

Charlie looked at the pay phone and suddenly shoved it.

A little grunt of effort escaped her, and she bit down on her lower lip, liking the way it squeezed under her teeth. No, there was no pain involved. It felt good to shove things, and that was another thing that scared her. Suppose she got to like this dangerous thing?

She shoved the pay phone again, very lightly, and suddenly a tide of silver poured out of the coin return. She tried to get her bag under it, but by the time she did, most of the quarters and nickels and dimes had spewed onto the floor. She bent over and swept as much as she could into the bag, glancing again and again out the window.

With the change picked up, she went on to the next booth. The serviceman was still talking on the next phone up the line. He had opened the door again and was smoking.

"Sal, honest to Christ I did!

Just ask your brother if you don't believe me! He'll-"

Charlie slipped the door shut, cutting off" the slightly whining sound of his voice. She was only seven, but she knew a snowjob when she heard one. She looked at the phone, and a moment later it gave up its change. This time she had the bag positioned perfectly and the coins cascaded to the bottom with a musical little jingling sound.

The serviceman was gone when she came out, and Charlie went into his booth. The seat was still warm and the air smelled nastily of cigarette smoke in spite of the fan.

The money rattled into her bag and she went on.

6

Eddie Delgardo sat in a hard plastic contour chair, looking "up at the ceiling and smoking. Bitch, he was thinking. She'll think twice about keeping her goddam legs closed next time. Eddie this and Eddie that and Eddie I never want to see you again and Eddie how could you be so crew-ool. But he had changed her mind about the old I-never-want-to-see-you-again bit. He was on thirty-day leave and now he was going to New York City, the Big Apple, to see the sights and tour the singles bars. And when he came back, Sally would be like a big ripe apple herself, ripe and ready to fall. None of that don't-you-have-any-respect-for-me stuff" went down with Eddie Delgardo of Marathon, Florida. Sally Bradford was going to put out, and if she really believed that crap about him having had a vasectomy, it served her right. And then let her go running to her hick schoolteacher brother if she wanted to. Eddie Delgardo would be driving an army supply truck in West Berlin. He would be-

Eddie's half resentful, half pleasant chain of daydreams was broken by a strange feeling of warmth coming from his feet; it was as if the floor had suddenly heated up ten degrees. And accompanying this was a strange but not completely unfamiliar smell... not something burning but... something singeing, maybe?

He opened his eyes and the first thing he saw was that little girl who had been cruising around by the phonebooths, little girl seven or eight years old, looking really ragged out. Now she was carrying a big paper bag, carrying it by the bottom as if it were full of groceries or something.

But his feet, that was the thing.

They were no longer warm. They were hot.

Eddie Delgardo looked down and screamed,

"Godamighty Jeesus!"

His shoes were on fire.

Eddie leaped to his feet. Heads turned. Some woman saw what was happening and yelled in alarm. Two security guards who had been noodling with an Allegheny Airlines ticket clerk looked over to see what was going on.

None of what meant doodly-squat to Eddie Delgardo. Thoughts of Sally Bradford and his revenge of love upon her were the furthest things from his mind. His army-issue shoes were burning merrily. The cuffs of his dress greens were catching. He was sprinting across the concourse, trailing smoke, as if shot from a catapult. The women's room was closer, and Eddie, whose sense of self preservation was exquisitely defined, hit the door straight-arm and ran inside without a moment's hesitation.

A young woman was coming out of one of the stalls, her skirt rucked up to her waist, adjusting her Underalls. She saw Eddie, the human torch, and let out a scream that the bathroom's tiled walls magnified enormously. There was a babble of "What was that?" and "What's going on?" from the few other occupied stalls. Eddie caught the paytoilet door before it could swing back all the way and latch. He grabbed both sides of the stall at the top and hoisted himself feet first into the toilet. There was a hissing sound and a remarkable billow of steam.

The two security guards burst in. "Hold it, you in there!" one of them cried. He had drawn his gun. "Come out of there with your hands laced on top of your head!" "You mind waiting until I put my feet out?" Eddie Delgardo snarled.

7

Charlie was back. And she was crying again. "What happened, babe?" "I got the money but... it got away from me again, Daddy... there was a man... a soldier... I couldn't help it..." Andy felt the fear creep up on him. It was muted by the pain in his head and down the back of his neck, but it was there. "Was... was there a fire, Charlie?"

She couldn't speak, but nodded. Tears coursed down her cheeks.

"Oh my God," Andy whispered, and made himself get to his feet.

That broke Charlie completely. She put her face in her hands and sobbed helplessly, rocking back and forth.

A knot of people had gathered around the door of the women's room. It had been propped open, but Andy couldn't see... and then he could. The two security guards who had gone running down there were leading a tough-looking young man in an army uniform out of the bathroom and toward the security office. The young man was jawing at them loudly, and most of what he had to say was inventively profane. His uniform was mostly gone below the knees, and he was carrying two dripping, blackened things that might once have been shoes. Then they were gone into the office, the door slamming behind them. An excited babble of conversation swept the terminal.

Andy sat down again and put his arm around Charlie. It was very hard to think now; his thoughts were tiny silver fish swimming around in a great black sea of throbbing pain. But he had to do the best he could. He needed Charlie if they were going to get out of this.

"He's all right, Charlie. He's okay. They just took him down to the security office. Now, what happened?"

Through diminishing tears, Charlie told him. Overhearing the soldier on the phone. Having a few random thoughts about him, a feeling that he was trying to trick the girl he was talking to. "And then, when I was coming back to you, I saw him... and before I could stop it... it happened. It just got away. I could have hurt him, Daddy. I could have hurt him bad. I set him on fire!"

"Keep your voice down," he said. "I want you to listen to me, Charlie. I think this is the most encouraging thing that's happened in some time." "Y-you do?" She looked at him in frank surprise.

"You say it got away from you," Andy said, forcing the words. "And it did. But not like before. It only got away a little bit. What happened was dangerous, honey, but... you might have set his hair on fire. Or his face."

She winced away from that thought, horrified. Andy turned her face gently back to his.

"It's a subconscious thing, and it always goes out at someone you don't like," he said. "But... you didn't really hurt that guy, Charlie. You..." But the rest of it was gone and only the pain was left. Was he still talking? For a moment he didn't even know.

Charlie could still feel that thing, that Bad Thing, racing around in her head, wanting to get away again, to do something else. It was like a small, vicious, and rather stupid animal. You had to let it out of its cage to do something like getting money from the phones... but it could do something else, something really bad.

(like mommy in the kitchen oh mom I'm sorry)

before you could get it back in again. But now it didn't matter. She wouldn't think about it now, she wouldn't think about

(the bandages my mommy has to wear bandages because i hurt her)

any of it now. Her father was what mattered now. He was slumped over in his TV chair, his face stamped with pain. He was paper white. His eyes were bloodshot.

Oh, Daddy, she thought, I'd trade even-Steven with you if I could. You've got something that hurts you but it never gets out of its cage. I've got something that doesn't hurt me at all but oh sometimes I get so scared-

"I've got the money," she said. "I didn't go to all the telephones, because the bag was getting heavy and I was afraid it would break." She looked at him anxiously. "Where can you go, Daddy? You have to lie down.".

Andy reached into the bag and slowly began to transfer the change in handfuls to the pockets of his corduroy coat. He wondered if this night would ever end. He wanted to do nothing more than grab another cab and go into town and check them into the first hotel or motel in sight... but he was afraid. Cabs could be traced. And he had a strong feeling that the people from the green car were still close behind.

He tried to put together what he knew about the Albany airport. First of all, it was the Albany County Airport; it really wasn't in Albany at all but in the town of Colonie. Shaker country-hadn't his grandfather told him once that this was Shaker country? Or had all of them died out now? What about highways? Turnpikes? The answer came slowly. There was a road... some sort of Way. Northway or Southway, he thought.

He opened his eyes and looked at Charlie. "Can you walk aways, kiddo? Couple of miles, maybe?" "Sure." She had slept and felt relatively fresh. "Can you?" That was the question. He didn't know. "I'm going to try," he said. "I think we ought to walk out to the main road and try to catch a ride, hon." "Hitchhike?" she asked.

He nodded. "Tracing a hitchhiker is pretty hard, Charlie. If we're lucky, we'll get a ride with someone who'll be in Buffalo by morning." And if we're not, we'll still be standing in the breakdown lane with our thumbs out when that green car comes rolling up.

"If you think it's okay," Charlie said doubtfully.

"Come on," he said, "help me."

Gigantic bolt of pain as he got to his feet. He swayed a little, closed his eyes, then opened them again. People looked surreal. Colours seemed too bright. A woman walked by on high heels, and every click on the airport tiles was the sound of a vault door being slammed.

"Daddy, are you sure you can?" Her voice was small and very scared.

Charlie. Only Charlie looked right.

"I think I can," he said. "Come on."

They left by a different door from the one they had entered, and the skycap who had noticed them getting out of the cab was busy unloading suitcases from the trunk of a car. He didn't see them go out.

"Which way, Daddy?" Charlie asked.

He looked both ways and saw the Northway, curving away below and to the right of the terminal building. How to get there, that was the question. There were roads everywhere-overpasses, underpasses. NO RIGHT TURN, STOP ON SIGNAL, KEEP LEFT, NO PARKING ANYTIME. Traffic signals flashing in the early-morning blackness like uneasy spirits.

"This way, I think," he said, and they walked the length of the terminal beside the feeder road that was lined with LOADING AND UNLOADING ONLY signs. The sidewalk ended at the end of the terminal. A large silver Mercedes swept by them indifferently, and the reflected glow of the overhead sodium arcs on its surface made him wince.

Charlie was looking at him questioningly.

Andy nodded. "Just keep as far over to the side as you can. Are you cold?"

"No, Daddy."

"Thank goodness it's a warm night. Your mother would-"

His mouth snapped shut over that.

The two of them walked off into darkness, the big man with the broad shoulders and the little girl in the red pants and the green blouse, holding his hand, almost seeming to lead him.

8

The green car showed up about fifteen minutes later and parked at the yellow curb. Two men got out, the same two who had chased Andy and Charlie to the cab back in Manhattan. The driver sat behind the wheel.

An airport cop strolled up. "You can't park here, sir," he said. "If you'll just pull up to-""Sure I can," the driver said. He showed the cop his ID. The airport cop looked at it, looked at the driver, looked back at the picture on the ID.

"Oh," he said. "I'm sorry, sir. Is it something we should know about?"

"Nothing that affects airport security," the driver said, "but maybe you can help. Have you seen either of these two people tonight?" He handed the airport cop a picture of Andy, and then a fuzzy picture of Charlie. Her hair had been longer then. In the snap, it was braided into pigtails. Her mother had been alive then. "The girl's a year or so older now," the driver said. "Her hair's a bit shorter. About to her shoulders."

The cop examined the pictures carefully, shuffling them back and forth. "You know, I believe I did see this little girl," he said. "Towhead, isn't she? Picture makes it a little hard to tell."

"Towhead, right."

"The man her father?"

"Ask me no questions, I'll tell you no lies."

The airport cop felt a wave of dislike for the bland-faced young man behind the wheel of the nondescript green car. He had had peripheral doings with the FBI, the CIA, and the outfit they called the Shop before. Their agents were all the same, blankly arrogant and patronizing. They regarded anyone in a bluesuit as a kiddy cop. But when they'd had the hijacking here five years ago, it had been the kiddy cops who got the guy, loaded down with grenades, off the plane, and he had been in custody of the "real" cops when he committed suicide by opening up his carotid artery with his own fingernails. Nice going, guys.

"Look... sir. I asked if the man was her father to try and find out if there's a family resemblance. Those pictures make it a little hard to tell."

"They look a bit alike. Different hair colors."

That much 1 can see for myself, you asshole, the airport cop thought. "I saw them both,"

the cop told the driver of the green car. "He's a big guy, bigger than he looks in that picture. He looked sick or something." "Did he?" The driver seemed pleased. "We've had a big night here, all told. Some fool also managed to light his own shoes on fire." The driver sat bolt upright behind the wheel. "Say what?"

The airport cop nodded, happy to have got through the driver's bored facade. He would not have been so happy if the driver had told him he had just earned himself a debriefing in the Shop's Manhattan offices. And Eddie Delgardo probably would have beaten the crap out of him, because instead of touring the singles bars (and the massage parlors, and the Times Square porno shops) during the Big Apple segment of his leave, he was going to spend most of it in a drug-induced state of total recall, describing over and over again what had happened before and just after his shoes got hot.

9

The other two men from the green sedan were talking to airport personnel. One of them discovered the skycap who had noticed Andy and Charlie getting out of the cab and going into the terminal.

"Sure I saw them. I thought it was a pure-d shame, a man as drunk as that having a little girl out that late." "Maybe they took a plane," one of the men suggested. "Maybe so," the skycap agreed. "I wonder what that child's mother can be thinking of. I wonder if she knows what's going on." "I doubt if she does," the man in the dark-blue Botany 500 suit said. He spoke with great sincerity. "You didn't see them leave?"

"No, sir. Far as I know, they're still round here somewhere... unless their flight's been called, of course."

10

The two men made a quick sweep through the main terminal and then through the boarding gates, holding their IDs up in their cupped hands for the security cops to see. They met near the United Airlines ticket desk.

"Dry," the first said. "Think they took a plane?" the second asked. He was the fellow in the nice blue Botany 500. "I don't think that bastard had more than fifty bucks to his name... maybe a whole lot less than that."

"We better check it."

"Yeah. But quick."

United Airlines. Allegheny. American. Braniff. The commuter airlines. No broad-shouldered man who looked sick had bought tickets. The baggage handler at Albany Airlines thought he had seen a little girl in red pants and a green shirt, though. Pretty blond hair, shoulder-length.

The two of them met again near the TV chairs where Andy and Charlie had been sitting not long ago. "What do you think?" the first asked. The agent in the Botany 500 looked excited. "I think we ought to blanket the area," he said. "I think they're on foot." They headed back to the green car, almost trotting.

11

Andy and Charlie walked on through the dark along the soft shoulder of the airport feeder road. An occasional car swept by them. It was almost one o'clock. A mile behind them, in the terminal, the two men had rejoined their third partner at the green car. Andy and Charlie were now walking parallel to the Northway, which was to their right and below them, lit by the depthless glare of sodium lights. It might be possible to scramble down the embankment and try to thumb a ride in the breakdown lane, but if a cop came along, that would end whatever poor chance they still had to get away. Andy was wondering how far they would have to walk before they came to a ramp. Each time his foot came down, it generated a thud that resounded sickly in his head.

"Daddy? Are you still okay?"

"So far, so good," he said, but he was not so very okay. He wasn't fooling himself, and he doubted if he was fooling Charlie.

"How much further is it?"

"Are you getting tired?"

"Not yet... but Daddy..."

He stopped and looked solemnly down at her. "What is it, Charlie?"

"I feel like those bad men are around again," she whispered.

"All right," he said. "I think we better just take a shortcut, honey. Can you get down that hill without falling?"

She looked at the grade, which was covered with dead October grass.

"I guess so," she said doubtfully.

He stepped over the guardrail cables and then helped Charlie over. As it sometimes did in moments of extreme pain and stress, his mind attempted to flee into the past, to get away from the stress. There had been some good years, some good times, before the shadow began to steal gradually over their lives-first just over him and Vicky, then over all three, blotting out their happiness a little at a time, as inexorably as a lunar eclipse. It had been-

"Daddy!" Charlie called in sudden alarm. She had lost her footing. The dry grass was slippery, treacherous. Andy grabbed for her flailing arm, missed, and overbalanced himself. The thud as he hit the ground caused such pain in his head that he cried out loud. Then they were both rolling and sliding down the embankment toward the Northway where the cars rushed past, much too fast to stop if one of them-he or Charlie-should tumble out onto the pavement.

12

The GA looped a piece of rubber flex around Andy's arm just above the elbow and said, "Make a fist, please." Andy did. The vein popped up obligingly. He looked away, feeling a little ill. Two hundred dollars or not, he had no urge to watch the IV set in place.

Vicky Tomlinson was on the next cot, dressed in a sleeveless white blouse and dove-gray slacks. She offered him a strained smile. He thought again what beautiful auburn hair she had, how well it went with her direct blue eyes... then the prick of pain, followed by dull heat, in his arm.

"There," the grad assistant said comfortingly.

"There yourself," Andy said. He was not comforted.

They were in Room 70 of Jason Gearneigh Hall, upstairs. A dozen cots had been trucked in, courtesy of the college infirmary, and the twelve volunteers were lying propped up on hypoallergenic foam pillows, earning their money. Dr. Wanless started none of the IVs himself, but he was walking up and down between the cots with a word for everyone, and a little frosty smile. We'll start to shrink anytime now, Andy thought morbidly.

Wanless had made a brief speech when they were all assembled, and what he had said, when boiled down, amounted to: Do not fear. You are wrapped snugly in the arms of Modern Science. Andy had no great faith in Modern Science, which had given the world the H-bomb, napalm and the laser rifle, along with the Salk vaccine and Clearasil.

The grad assistant was doing something else now. Crimping the IV line.

The IV drip was five percent dextrose in water, Wanless had said... what he called a D5W solution. Below the crimp, a small tip poked out of the IV line. If Andy got Lot Six, it would be administered by syringe through the tip. If he was in the control group, it would be normal saline. Head or tails.

He glanced over at Vicky again. "How you doin, kid?"

"Okay."

Wanless had arrived. He stood between them, looking first at Vicky and then at Andy. "You feel some slight pain, yes?" He had no accent of any kind, least of all a regional-American one, but he constructed his sentences in a way Andy associated with English learned as a second language.

"Pressure," Vicky said. "Slight pressure."

"Yes? It will pass." He smiled benevolently down at Andy. In his white lab coat he seemed very tall. His glasses seemed very small. The small and the tall.

Andy said, "When do we start to shrink?"

Wanless continued to smile. "Do you feel you will shrink?"

"Shhhhrrrrrink," Andy said, and grinned foolishly. Something was happening to him. By God, he was getting high. He was getting off.

"Everything will be fine," Wanless said, and smiled more widely. He passed on. Horseman, pass by, Andy thought bemusedly. He looked over at Vicky again. How bright her hair was! For some crazy reason it reminded him of the copper wire on the armature of a new motor... generator... alternator... flibbertigibbet...

He laughed aloud.

Smiling slightly, as if sharing the joke, the grad assistant crimped the line and injected a little more of the hypo's contents into Andy's arm and strolled away again. Andy could look at the IV line now. It didn't bother him now. I'm a pine tree, he thought. See my beautiful needles. He laughed again.

Vicky was smiling at him. God, she was beautiful. He wanted to tell her how beautiful she was, how her hair was like copper set aflame. "Thank you," she said. "What a nice compliment." Had she said that? Or had he imagined it? Grasping the last shreds of his mind, he said, "I think I crapped out on the distilled water, Vicky."

She said placidly, "Me too."

"Nice, isn't it?"

"Nice," she agreed dreamily.

Somewhere someone was crying. Babbling hysterically. The sound rose and fell in interesting cycles. After what seemed like eons of contemplation, Andy turned his head to see what was going on. It was interesting. Everything had become interesting. Everything seemed to be in slow motion. Slomo, as the avant-garde campus film critic always put it in his columns. In this film, as in others, Antonioni achieves some of his most spectacular effects with his use of slomo footage. What an interesting, really clever word; it had the sound of a snake slipping out of a refrigerator: slomo.

Several of the grad assistants were running in slomo toward one of the cots that had been placed near Room 70's blackboard. The young fellow on the cot appeared to be doing something to his eyes. Yes, he was definitely doing something to his eyes, because his fingers were hooked into them and he seemed to be clawing his eyeballs out of his head. His hands were hooked into claws, and blood was gushing from his eyes. It was gushing in slomo. The needle flapped from his arm in slomo. Wanless was running in slomo. The eyes of the kid on the cot now looked like deflated poached eggs, Andy noted clinically. Yes indeedy.

Then the white coats were all gathered around the cot, and you couldn't see the kid anymore. Directly behind him, a chart hung down. It showed the quadrants of the human brain. Andy looked at this with great interest for a while. Verrry in-der-rresting, as Arte Johnson said on Laugh-In.

A bloody hand rose out of the huddle of white coats, like the hand of a drowning man. The fingers were streaked with gore and shreds of tissue hung from them. The hand smacked the chart, leaving a bloodstain in the shape of a large comma. The chart rattled up on its roller with a smacking sound.

Then the cot was lifted (it was still impossible to see the boy who had clawed his eyes out) and carried briskly from the room. A few minutes (hours? days? years?) later, one of the grad assistants came over to Andy's cot, examined his drip, and then injected some more Lot Six into Andy's mind.

"How you feeling, guy?" the GA asked, but of course he wasn't a GA, he wasn't a student; none of them were. For one thing, this guy looked about thirty-five, and that was a little long in the tooth for a graduate student. For another, this guy worked for the Shop. Andy suddenly knew it. It was absurd, but he knew it. And the man's name was...

Andy groped for it, and he got it. The man's name was Ralph Baxter.

He smiled. Ralph Baxter. Good deal.

"I feel okay," he said. "How's that other fella?"

"What other fella's that, Andy?"

"The one who clawed his eyes out," Andy said serenely.

Ralph Baxter smiled and patted Andy's hand. "Pretty visual stuff', huh, guy?"

"No, really," Vicky said. "I saw it, too."

"You think you did," the GA who was not a GA said. "You just shared the same illusion. There was a guy over there by the board who had a muscular reaction... something like a charley horse. No clawed eyes. No blood."

He started away again.

Andy said, "My man, it is impossible to share the same illusion without some prior consultation." He felt immensely clever. The logic was impeccable, inarguable. He had old Ralph Baxter by the shorts.

Ralph smiled back, undaunted. "With this drug, it's very possible," he said. "I'll be back in a bit, okay?"

"Okay, Ralph," Andy said.

Ralph paused and came back toward where Andy lay on his cot. He came back in slomo. He looked thoughtfully down at Andy. Andy grinned back, a wide, foolish, drugged-out grin. Got you there, Ralph old son. Got you right by the proverbial shorts. Suddenly a wealth of information about Ralph Baxter flooded in on him, tons of stuff: he was thirty-five, he had been with the Shop for six years, before that he'd been with the FBI for two years, he had-

He had killed four people during his career, three men and one woman. And he had raped the woman after she was dead. She had been an AP stringer and she had known about-

That part wasn't clear. And it didn't matter. Suddenly Andy didn't want to know. The grin faded from his lips. Ralph Baxter was still looking down at him, and Andy was swept by a black paranoia that he remembered from his two previous LSD trips... but this was deeper and much more frightening. He had no idea how he could know such things about Ralph Baxter-or how he had known his name at all-but if he told Ralph that he knew, he was terribly afraid that he might disappear from Room 70 of Jason Gearneigh with the same swiftness as the boy who had clawed his eyes out: Or maybe all of that really had been a hallucination; it didn't seem real at all now.

Ralph was still looking at him. Little by little he began to smile. "See?" he said softly. "With Lot Six, all kinds of funky things happen."

He left. Andy let out a slow sigh of relief. He looked over at Vicky and she was looking back at him, her eyes were wide and frightened. She's getting your emotions, he thought. Like a radio. Take it easy on her! Remember she's tripping, whatever else this weird shit is!

He smiled at her, and after a moment, Vicky smiled uncertainly back. She asked him what was wrong. He told her he didn't know, probably nothing.

(but we're not talking-her mouth's not moving)

(it's not?)

(vicky? is that you)

(is it telepathy, andy? is it?)

He didn't know. It was something. He let his eyes slip closed.

Are those really grad assistants? she asked him, troubled. They don't look the same. Is it the drug, Andy? I don't know, he said, eyes still closed. I don't know who they are. What happened to that boy? The one they took away? He opened his eyes again and looked at her, but Vicky was shaking her head. She didn't remember. Andy was surprised and dismayed to find that he hardly remembered himself. It seemed to have happened years ago. Got a charley horse, hadn't he, that guy? A muscular twitch, that's all. He-

Clawed his eyes out.

But what did it matter, really?

Hand rising out of the huddle of white coats like the hand of a drowning man.

But it happened a long time ago. Like in the twelfth century.

Bloody hand. Striking the chart. The chart rattling up on its roller with a smacking sound.

Better to drift. Vicky was looking troubled again.

Suddenly music began to flood down from the speakers in the ceiling, and that was nice... much nicer than thinking about charley horses and leaking eyeballs. The music was soft and yet majestic. Much later, Andy decided (in consultation with Vicky) that it had been Rachmaninoff. And ever after when he heard Rachmaninoff, it brought back drifting, dreamy memories of that endless, timeless time in Room 70 of Jason Gearneigh Hall.

How much of it had been real, how much hallucination? Twelve years of off-and-on thought had not answered that question for Andy McGee. At one point, objects had seemed to fly through the room as if an invisible wind were blowing-paper cups, towels, a blood-pressure cuff, a deadly hail of pens and pencils. At another point, sometime later (or had it really been earlier? there was just no linear sequence), one of the test subjects had gone into a muscular seizure followed by cardiac arrest-or so it had seemed. There had been frantic efforts to restore him using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, followed by a shot of something directly into the chest cavity, and finally a machine that made a high whine and had two black cups attached to thick wires. Andy seemed to remember one of the "grad assistants" roaring, "Zap him! Zap him! Oh, give them to me, you fuckhead!"

At another point he had slept, dozing in and out of a twilight consciousness. He spoke to Vicky and they told each other about themselves. Andy told her about the car accident that had taken his mother's life and how he had spent the next year with his aunt in a semi-nervous breakdown of grief. She told him that when she was seven, a teenage babysitter had assaulted her and now she was terribly afraid of sex, even more afraid that she might be frigid, it was that more than anything else that had forced her and her boyfriend to the breakup. He kept... pressing her.

They told each other things that a man and a woman don't tell each other until they've known each other for years... things a man and a woman often never tell, not even in the dark marriage bed after decades of being together.

But did they speak?

That Andy never knew.

Time had stopped, but somehow it passed anyway.

13

He came out of the doze a little at a time. The Rachmaninoff was gone... if it had ever been there at all. Vicky was sleeping peacefully on the cot beside him, her hands folded between her breasts, the simple hands of a child who has fallen asleep while offering her bedtime prayers. Andy looked at her and was simply aware that at some point he had fallen in love with her. It was a deep and complete feeling, above (and below) question.

After a while he looked around. Several of the cots were empty. There were maybe five test subjects left in the room. Some were sleeping. One was sitting up on his cot and a grad assistant-a perfectly normal grad assistant of perhaps twenty-five-was questioning him and writing notes on a clipboard. The test subject apparently said something funny, because both of them laughed in the low, considerate way you do when others around you are sleeping.

Andy sat up and took inventory of himself. He felt fine. He tried a smile and found that it fit perfectly. His muscles lay peacefully against one another. He felt eager and fresh, every perception sharply honed and somehow innocent. He could remember feeling this way as a kid, waking up on Saturday morning, knowing his bike was heeled over on its kickstand in the garage, and feeling that the whole weekend stretched ahead of him like a carnival of dreams where every ride was free.

One of the grad assistants came over and said, "How you feeling, Andy?"

Andy looked at him. This was the same guy that had injected him-when? A year ago? He rubbed a palm over his cheek and heard the rasp of beard stubble. "I feel like Rip van Winkle," he said.

The GA smiled. "It's only been forty-eight hours, not twenty years. How do you feel, really?"

"Fine."

"Normal?"

"Whatever that word means, yes. Normal. Where's Ralph?"

"Ralph?" The GA raised his eyebrows.

"Yes, Ralph Baxter. About thirty-five. Big guy. Sandy hair."

The grad assistant smiled. "You dreamed him up," he said.

ePub

ePub A4

A4